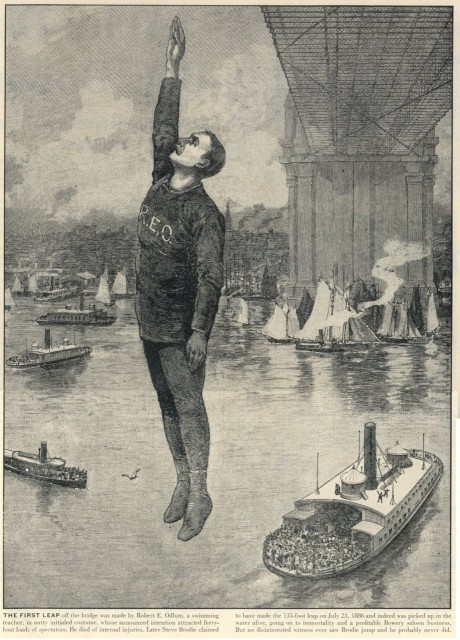

Science fiction writer Douglas Adams’ famous quote, “It’s not the fall that kills you; it’s the sudden stop at the end,” is a modern cliche. But at one time, it was unheard of. In New York, in the late 1800’s, when tall buildings and skyscrapers began to appear, some caught fire. Their occupants were beyond the reach of fire department ladders, but they were afraid to jump into safety nets held below, believing that plummeting from a height would suffocate them.

Enter Robert Emmet Odlum, a swimming instructor from Washington, DC with a passion for safety. He believed that everyone should learn to swim, and learn to jump in a high-rise fire. He made it his mission to prove that you could breath while falling. He did so successfully from a series of ever-greater heights. At least for awhile.

By 1885, the Brooklyn Bridge had become an object of fascination. Having previously jumped from 110 feet, expectations grew that he would become the first to jump 130 feet from this famous bridge, into the East River. It didn’t work out well. Evading police efforts to prevent it, with thousands of onlookers watching, he jumped at approximately 5:30 on May 19. He held one hand high above his head as a rudder to try to control his descent. But he began to slant. His right side impacted the water and he disappeared. When he surfaced, he was floating face down. He was rescued from the water, unconscious. He briefly showed signs of life, opened his eyes and asked if he had made a good jump. However, he had ruptured his kidneys, liver, and spleen, and died of his injuries less than an hour after his jump. Despite the sad outcome, Odlum became famous. Others then tried to capitalize on it by taking the same leap into the East River, or at least pretending to.

The second bridge jumper was Steve Brodie, described by the New York Times as “a newsboy and long-distance pedestrian.” Either he jumped from the Brooklyn Bridge, or a dummy did so while Brodie fell out of a row boat, on July 23 in 1886. His motives were not nearly as altruistic. Either he wanted to win a $200 bet, or he wanted to be famous. That, he did accomplish. He also opened a saloon at 114 Bowery near Grand Street, which he fashioned into his own bridge-jumping museum. His fame lives on today: in the slang phrase, “do a Brodie,” meaning to take a suicidal leap; and in the 1965 musical Kelly, inspired by Brodie’s story, so bad that it flopped on opening night – a sudden stop if there ever was one.

— Carol Cofone

| 1885 | Robert Emmet Odlum jumps off the Brooklyn Bridge and dies |

| 1886 | Steve Brody does or doesn’t jump off the Brooklyn Bridge and lives |

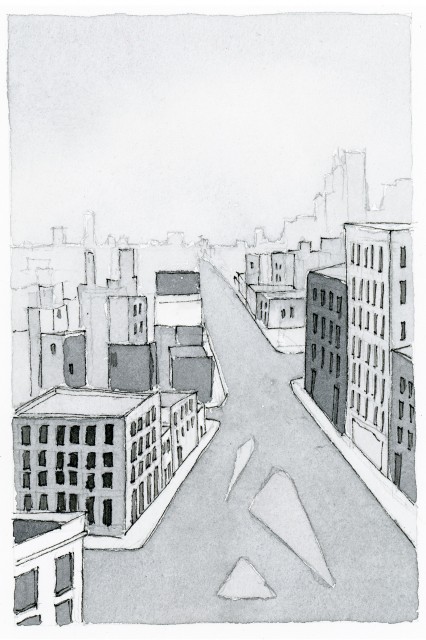

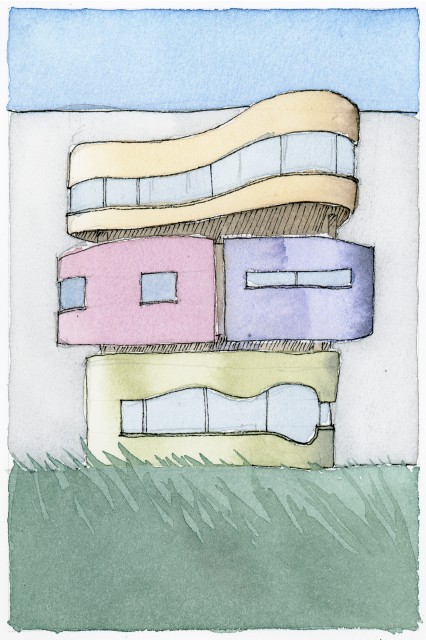

The new condominium is located at the corner of Lafayette and Bond Street in New York’s NoHo neighborhood, a district characterized by loft buildings with a high level of craftsmanship. The design for this 34,000 sf building is a contemporary reflection of the neighborhood’s architectural traditions with a sculpted terracotta façade and weathered steel details. The seven story building contains ten, two or three bedroom units including a maisonette unit and a penthouse with a large trellis-covered terrace. Retail shops and an entrance lobby are located on the ground level, which is distinguished by a façade of rich mahogany, slate, and glass.

Selldorf Architects is a 65-person architectural design practice that was founded by Annabelle Selldorf in 1988. The firm has worked on public and private projects that range from museums and libraries to a recycling facility, and at scales encompassing large new construction, historic renovations, and exhibition design. Creating buildings that are both contemporary and timeless is a fundamental goal of the firm. The practice designs buildings and public spaces that are an integrated and authentic reflection of the cities and institutions they serve. Projects evolve in response to their specific context and program, drawing influence from local materials and building traditions. This context-driven approach is guided by rigor, precision, and restraint.

— Lilia Carrier

| link | 10 Bond Street Website |

| link | Selldorf Architects |

The gummy bear originated in Germany, where it is popular under the name Gummibär or in the endearing form Gummibärchen, gum arabic was the original base ingredient used to produce the gummy bears, hence the name gum or gummy. Hans Riegel, Sr., a confectioner from Bonn, started the Haribo company in 1920. In 1922, inspired by the trained bears seen at street festivities and markets in Europe through to the 19th century, he invented the Dancing Bear (Tanzbär), a small, affordable, fruit-flavored gum candy treat for children and adults alike, which was much larger in form than its later successor, the Gold-Bear (Goldbär). Even during Weimar Germany’s hyperinflation period that wreaked havoc on the country, Haribo’s fruit-gum Dancing Bear treats remained affordably priced for a mere 1 Pfennig, in pairs, at kiosks. The success of the Dancing Bear’s successor would later become Haribo’s world-famous Gold-Bears candy product in 1967.

via Wikipedia

| wiki | Haribo |

| wiki | Gummy Bear |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Addresses of NYC artists |

The now bricked up doorway in the Clinton Hall Lexington Avenue subway station often goes unnoticed, but it holds an interesting history. The plaque above the old doorway inscribed “Clinton Hall” once connected the station to 21 Astor Place which, at the time, was the old New York Mercantile Library. The library was one of the largest periodical subscriptions in the city, and it also held lectures by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Mark Twain. Before Clinton Hall, however, 21 Astor was the site of the Astor Place Opera House where the infamous 1849 Shakespeare Riots took place.

On May 7th, a riot broke out over which actor–American actor Edwin Forest or British actor William Charles Macready–could better perform Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Macbeth. The English-American tension at the heart of the riots stretched back to the Revolutionary War, when arguments raged over whether the English or the British were going to rule New York. With the famous Five Points gangs backing Forest and the upper classes backing Macready, violence broke out at the theater. Armed militia shot into the crowd of 10,000 in an attempt to stop the protests and ended up killing at least 25 civilians.

Not long after the riots, the theater closed down and became the Mercantile Library. In 1904, the Opera House building was torn down and replaced with the building that stands there today.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | When Astor Place Was a Riot |

| internal | Clinton Hall at Astor Place |

| internal | The Forgotten Entrance to Clinton Hall |

| internal | Astor Place Riot |

Pritzker Prize winner Norman Foster (Gherkin, Boston MFA, Reichstag) received criticism from art critics and Bowery residents alike when 257 Bowery was first built. The building, home to the Sperone Westwater Gallery for contemporary art, is recognizable from its glass facade and distinctive red freight elevator. Taller and sleeker than its neighboring brick buildings, it does not fit into the neighborhood and can be seen as a sign of gentrification. After the building’s completion in 2010, sculptor and real estate developer Charles Saulson vandalized the gallery facade by pulling off the siding and throwing poop at 257 Bowery. His reasons were not out of dislike for the Starchitect’s space; he also claimed that the construction had caused structural problems with his building next door.

| 2010 | building completed |

| 2008 | start of design process |

| link | Charles Saulson |

| link | Sperone Westwater Gallery |

| link | Foster + Partners |

| article | Curbed |

| article | New York Times |

The Bowery was once known as a seedy, dilapidated neighborhood—and rightfully so. Its reputation throughout its history has been spotty, and recent upgrades have marked the first time in over a century that the area attracted visitors. And with all that grit comes a rich and fascinating history. The stories of the Bowery are stories of determination, passion, and changing the world. But before we begin, let’s take a look at what shaped the Bowery through its rocky past to its optimistic future.

The name “Bowery,” in fact, comes from an old Dutch word for farmhouse, “bouwerij,” and is one of New York’s oldest thoroughfares. By the 1700s, the neighborhood slowly transformed into a leisure destination for Manhattanites. The rich and famous started to move in by the 1800s, including Peter Cooper, who we’ll learn more about later on.

Around the middle of the 1800s, the neighborhood started its infamous decline. Brothels, pawn shops, and flophouses moved in. The area was starting to become known as Little Germany, and with that also came beer halls. One of America’s first street gangs, the Bowery Boys, was established. Prostitution was not hard to find. Although immigrant populations changed, the area remained in this state of disrepair through much of the 1900s, earning the reputation as the Skid Row of New York City by the middle of the century.

Finally in the 1970s, the city decided to step in. The area has slowly been revitalized. The New Museum stands as one of the more modern structures, and flophouses have been replaced with luxury residences. The grittiness is still around, but it’s subsiding.

On today’s tour, we’ll look through the history of the Bowery and explore some of its most famous residents, artists, and entrepreneurs. Let’s get started!

| 1880 | Bowery Mission opens |

| 1883 | Brooklyn Bridge opens, turning the Bowery into an economic center |

| link | National Register of Historic Places Program: The Bowery Historic District |

| internal | Bowery Slideshow PDF |

| internal | Bowery Wikipedia |

| internal | Bowery Timeline PDF |

| internal | New York Magazine: Down and Out |

| internal | gDoc |

Tony Goldman was a real estate developer whose buildings and love of the arts helped shaped the Soho we know today. Goldman eschewed the term “developer” in favor of describing himself as a long-term investor. He believed not just in building, but in revitalizing neighborhoods. In the mid-to-late-1970s, at a time when Soho was a run-down place that most developers overlooked, Goldman saw the potential of its large, open, industrial spaces that were transformed by artists into livable lofts.

Goldman Properties is responsible for many buildings in New York, including 25 Bond Street and the commissioned Ken Hiratsuka work in front it. They also commissioned the Francoise Schein piece, Subway Map Floating on a NY Sidewalk, in front of their offices at 110 Greene Street.

He passed away in 2012 at the age of 68, and today his daughter runs Goldman Properties. Between New York and Miami, where most of their projects are, they continue to promote the ideas of urban revitalization and public art.

| link | The SoHo Building |

| article | NY Times: Tony Goldman Obituary |

| article | Tony Goldman is SoHo Cool |

| internal | Tony Goldman - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

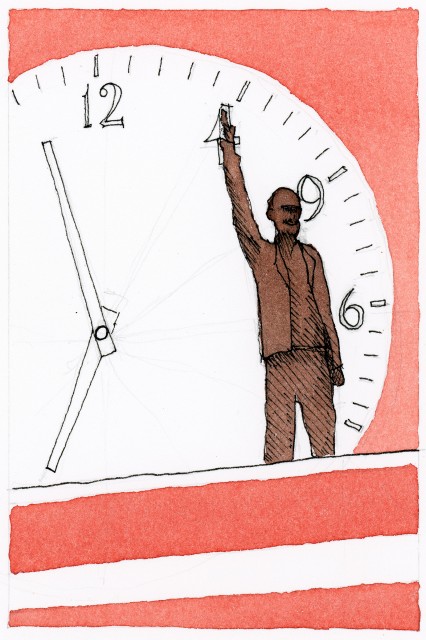

Born in Hungary in 1949, Tibor Kalman grew up in the United States and became a well known graphic designer. He co-founded design firm M & Co., which, though closed in 1992, has works that can still be seen in both the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum and the Museum of Modern Art, including replicas of the clock he made for the roof of the Red Square building. He was also the founding editor-in-chief of Colors magazine, sponsored by Benetton. Their most famous issue was the race issue, which showed recognizable people, such as Queen Elizabeth and the Pope, as racial minorities. Kalman was married to Maira Kalman, who helped run M & Co. and is a journalist, illustrator and artist known for her covers on The New Yorker. They were married until Tibor’s untimely death due to non-Hodgkins lymphoma at the young age of 49.

| 1990 | Tibor Kalman became editor-in-chief of Colors magazine |

| link | New York Times: Tibor Kalman, 'Bad Boy' of Graphic Design, 49, Dies |

| link | AIGA: Tibor Kalman |

| internal | Tibor Kalman - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

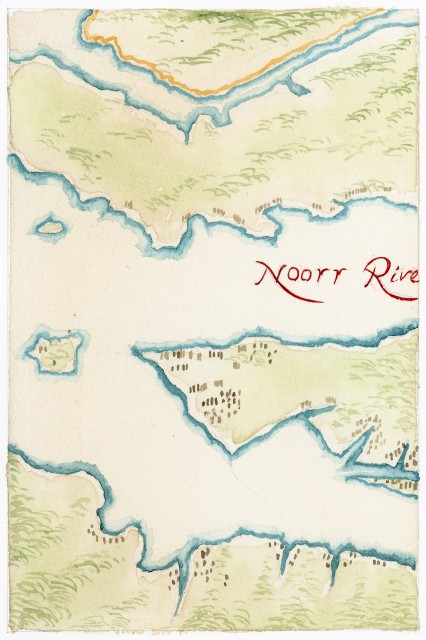

Created in 1639, the Manatus Map is the earliest known drawing of New York City. The full name, “Manatus Gelegen op de Noot Rivier,” or “Manatus located on the North River,” refers to the Dutch name for what is known today as the Hudson River. The map shows many individual farms and plantations, as well as both Conyne and Staten Eylandts. Exactly who drew it is still a mystery, but historians think it was likely the cartographer for the Prince of Nassau for the West India Company of Holland, Johannes Vingboons, or cartographer Joan Vinckeboons. Currently the map is housed at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

| 1639 | Johannes Vingboons draws Manatus Map |

| link | Library of Congress: Manatus Map |

| article | Interpreting the Little-Known Minuit Maps of c. 1630 |

| internal | Johannes Vingboons - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

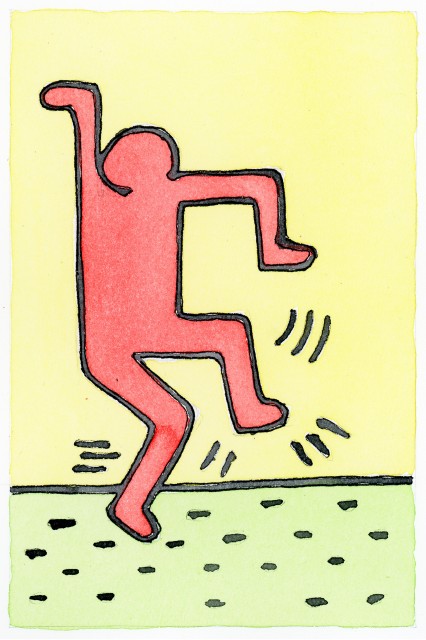

Keith Haring was an American artist known for his playful, cartoon-like images that evoked much heavier themes of sexuality, AIDS, birth, death, and war. Haring became popular in his early twenties in 1980, with both graffiti and gallery exhibitions. In 1983, he and friend Juan Dubose painted the Houston Bowery Mural with Haring’s iconic images, which made him an even bigger name in the art world. His group of friends included Jean-Michel Basquiat, Madonna, and the group around Andy Warhol.

Haring died in 1990 of AIDS-related complications. Even at a time when little was known about the disease, he was never shy about his diagnosis, speaking openly about safe sex and establishing the Keith Haring Foundation a year before his death in order to handle the licensing of his art and also provide funding to AIDS organizations and children’s programs. Today Haring’s works can be seen all over the world. Here in New York, we have a mural at the Tony DePolito swimming pool in the West Village, the infamous “Crack Is Wack” mural in Harlem and his altarpiece “Life of Christ” at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

| 1978 | Haring moves to New York and enrolls at the School of Visual Arts |

| 1988 | Haring diagnosed with AIDS |

| 1989 | Keith Haring Foundation established |

| 1990 | Haring passes away from AIDS-related complications |

| link | Keith Haring Foundation |

| internal | Keith Haring - Wiki |

| internal | Red List |

| internal | gDoc |

John Hejduk was a graduate of Cooper Union who later served as Dean of the School of Architecture for 25 years and also as an influential professor. Although Hejduk constructed relatively few buildings in his lifetime, he is well known for his contributions of written works and education in the field, and he was most interested in how spaces and shapes were organized and represented throughout buildings. Prior to teaching, he worked in the offices of I. M. Pei, who designed the Silver Towers and commissioned the Bust of Sylvette for New York University. Hejduk passed away a few weeks shy of his 71st birthday in 2000, and in 2003 Cooper Union established the John Q. Hejduk Award, which is given to graduates who have made an outstanding contribution in architecture.

| 1953 | Graduates with a Masters in Architecture from Harvard Graduate School of Design |

| 1964 | Becomes Professor of Architecture at Cooper Union |

| 1965 | Establishes his own architecture practice in New York |

| 1975 | Becomes Dean of the School of Architecture at Cooper Union |

| 2000 | Dies at age 70 |

| link | John Hejduk Works - Cooper Union |

| internal | John Hejduk - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

Jay Maisel is a photographer known both for his photographs as well as his residence at the Germania Bank Building, which he bought in 1966 for $102,000, or just under $750,000 in today’s money. His purchase is said to be New York best real estate deal, with the improvement of the neighborhood and scarcity of New York real estate, the building is valued at close to $50 million. He renovated the interior to make the top two floors a living area for his family and the lower three floors a studio and storage for his art.

Maisel has photographed many celebrities and magazine covers and has been awarded numerous photography honors. But one of his most well known pieces is the cover of Miles Davis’ 1959 album, “Kind of Blue.” Fifty years later, entrepreneur and blogger Andy Baio produced “Kind of Bloop,” a synthesized electronic version of Davis’ album with a pixelated version of Maisel’s original piece on the cover. While a wonderful project and idea, there was some controversy: Baio secured all the rights to the music, he overlooked securing the rights to the cover photo and ended up paying $32,500 in an out-of-court settlement to Maisel.

| 1966 | Purchased the Germania Bank Building for $102,000 |

| article | Faded and Blurred - It's About the Work: Jay Maisel |

| article | Waxy.org Blog: Kind of Screwed |

| internal | Jay Maisel - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

222 Bowery was built in 1885 as a YMCA, but it joins our tour due to its more recent history. By World War II it was being rented out as apartments, and it soon became an enclave for artists. French painter Fernand Leger lived here in the 1940s, and Mark Rothko moved in in the 1950s. Rothko rented the basement—which had been the gym at the Y—complete with lockers and communal showers. It’s where his infamous Seagram Murals were painted, the paintings commissioned for the restaurant in the new building of the beverage company that Rothko famously reneged on.

The resident who gave the building its moniker of “The Bunker” was William Burroughs, who made his home—and this building—the epicenter of the Bowery art community in the 1970s. It was the hub of the Beat Generation, a group of post-WWII writers who rejected cultural norms and pushed the boundaries of style, drugs, sexuality, and their writing. Burroughs’ famous colleagues included Alan Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, both of who spent time here.

Other guests of Burroughs included Jean-Michel Basquiat, Dennis Hopper, Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, Lou Reed, Patti Smith, Susan Sontag, and a friend, poet John Giorno. Many would stay for days at a time, partaking in bacchanalian festivities and multi-day drug binges.

Burroughs himself was most famous for his 1959 book Naked Lunch, which was so controversial that it caused an obscenity trial to be held. Burroughs was born into a wealthy midwest family in 1914, he studied English and Anthropology at Harvard and medicine in Vienna, he was a drug addict who struggled with sobriety much of his life. He moved away from the counterculture scene of New York to quieter Kansas in 1981, which is where he lived until his death of a heart attack in 1997.

Today his home at The Bunker remains intact, and the building is a landmark. John Giorno owns and maintains the apartment, and it appears just as it did when Burroughs lived there, although it is unfortunately not open to the public.

| 1884 | 222 Bowery built |

| 1958 | Rothko leased space to work on his mural series |

| 1962 | Michael Goldberg took over studio space from Rothko |

| 1972 | Lynda Benglis moves in |

| 1974 | William Burroughs moves in |

| 1977 | Llyn Umlaf moves in |

| 1997 | Burroughs dies, Giorno preserves The Bunker |

| sight | New Museum |

| sight | Basquiat's Loft |

| tidbit | Keith Haring |

| tidbit | Mark Rothko |

| article | William Burroughs - in pictures |

| article | Bohemian Rhapsody |

| article | Inside William Burroughs's Bowery Apartment |

| internal | Art Nerd |

| internal | Photographing William S. Burroughs |

| internal | Photographing William S. Burroughs |

| internal | 14 Photographs of personal items belonging to author William S. Burroughs |

| internal | gDoc |

| movie | William S. Burroughs: A Man Within |

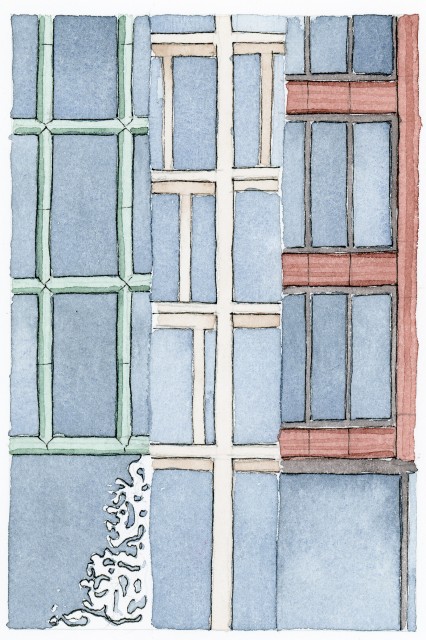

As you stroll down the charming and cobblestoned Bond Street, you’ll come across a few modern buildings, and there are two that are particularly interesting: 25 and 40 Bond, which are almost opposite each other. Both are ultra-luxury residences, built in 2007, and while they seem very different at first glance, they are actually similar in many ways. Each one brings a unique energy to the street, and the distinctions between the two highlights the role of architecture in defining a cityscape and the way people interact with the city.

25 Bond was built by one of our favorite developers, Goldman Properties. Tony Goldman, who was not only a very conscientious developer but also a great patron of the arts, makes his mark on Bond Street with this 8-storey, 9-unit building. Architects BKSK, a New York-based firm, made the facade asymmetric and layered; if you look closely, you’ll see the windows are bigger than they first appear since they continue behind the exterior columns. The layered look and Jerusalem limestone give the building an understated and rather tranquil look, making it almost temple-like—which is fitting since the stone is the same type used for the Western Wall in Jerusalem.

40 Bond, on the other hand, is flashier. The 11-storey building has a facade that seems fluid, unlike the solid stone structure of 25 Bond. The green shades change depending on the light and angle, like a gem. It was the first residential project of Swiss Architects Herzog & de Meuron, who are well known for the Bird’s Nest arena created for the Beijing Olympics.

Both buildings are gridlike, and yet both also have a decidedly unorderly jumble at their bases. 25 Bond boasts a piece by Ken Hiratsuka on the sidewalk (and another in the lobby, which you can see through the window). This work is part of Hiratsuka’s One Line series, which is a string of curvy lines chiseled by hand into stone around the world. There are more pieces in this series throughout NYC, such as this one in Soho. Contrast the almost prehistoric carvings in front of 25 Bond with the modern graffiti-like privacy fence at 40 Bond. The architects partnered with fine art foundry Polich Tallix, who created a compilation of actual graffiti tags found around the city.

The developers for each of these buildings also have their own unique stories. Tony Goldman is a patron of the arts who has had a huge impact on SoHo from both a development and an art standpoint. 40 Bond was developed by Ian Schrager and his friend Aby Rosen. Schrager is best known as a former partner and manager of some of New York’s most famous nightclubs, including Studio 54 and the Palladium, which were frequented in the 1970s by the in-scene, famous, and up-and-coming artists.

Beyond these pieces of architecture as art, Bond Street has been part of the artistic community for decades. Photographer Robert Maplethorpe kept a studio at number 24, and Keith Haring had a studio around the corner on Broadway. Currently Chuck Close, once known for his huge hyperrealistic portraits and now—after a spinal artery collapse that left him partially paralyzed—known for similar portraits done in a more interpretive, pixelated way, keeps his studio on the corner at 20 Bond.

| 1805 | City council creates plans for Bond Street |

| 2007 | 25 Bond completed |

| tidbit | Tony Goldman |

| sight | Broadway Sidewalk |

| sight | Subway Map Floating on a New York Sidewalk |

| tidbit | Keith Haring |

| link | BKSK Architects: 25 Bond |

| internal | NY Curbed: 25 Bond |

| internal | NYTimes Streetscapes / Bond Street |

| internal | gDoc |

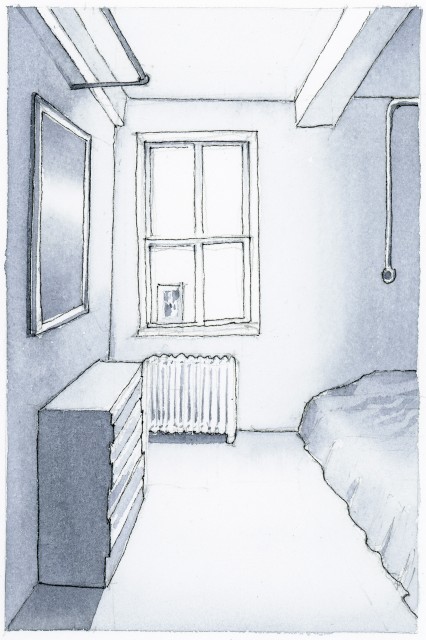

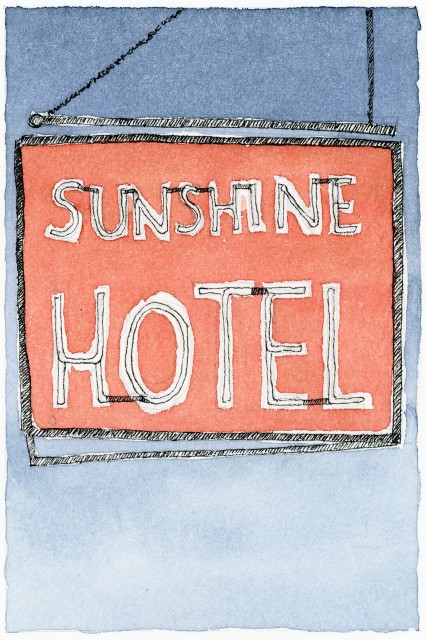

Although the Sunshine Hotel has closed, we include this stop at 245 Bowery on our tour because it was the last of the flophouses—low-cost, no-amenity accommodations that gave much needed shelter to men who had seen better days. The flophouses were part of life on the Bowery and contributed to its gritty yet neighborly vibe. The beds were either a cot in a shared room or a “cubicle,” which was a 4’x6’ (1.2m x 1.8m) wide and 7’ (2.1m) tall wooden frame, covered with chicken wire, that contained a bed, locker, and light bulb. Even in the 2000s the beds rented for just $4.50-$10 per night, keeping men out of shelters and giving them spaces of their own.

The Sunshine Hotel was made famous due to a 1998 radio documentary by David Isay and a 2001 film documentary by Michael Donovan. Both featured Nathan Smith, who found himself at the Sunshine after he lost his job and left his wife on the same day in the 1980s. He went on to become the manager of the hotel until he died in 2002. He was a friendly character who could usually be found at the checkin desk on the second floor, called the “cage” in flophouse terms.

The Sunshine saw all types come through its doors, from upstanding citizens who were down on their luck to hardened criminals. Its walls contained a microcosm of society. Many men preferred paying the small price for this community to staying in shelters. Eventually the neighborhood’s flophouses were pushed to the outskirts of the city and out of Manhattan altogether. The old Sunshine building houses a high-end diner, and next door is the New Museum, a literal illustration of how shiny, new buildings are replacing the old grit of the Bowery.

| 1922 | Sunshine Hotel opens |

| link | Bowery Will Have Sunshine For A Little Longer |

| internal | NYTimes Flophouses |

| link | All Things Considered: Sunshine Hotel |

| internal | gDoc |

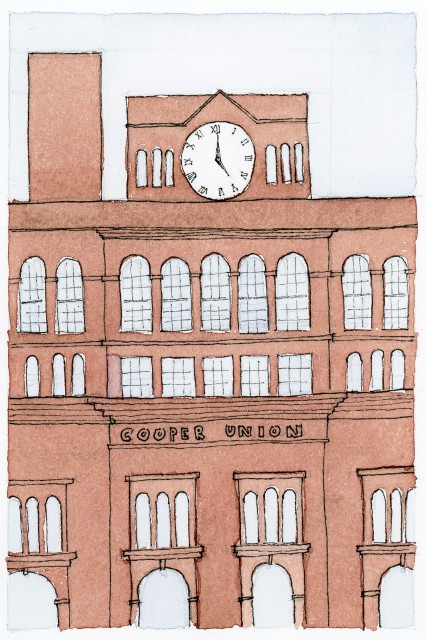

Peter Cooper, a New York City-born boy from humble roots, grew up to become an influential businessman and education advocate whose legacy helped define New York City. He founded Cooper Union, a tuition-free school built in the 1850s, to help see his vision of a time when “knowledge shall cover the earth as waters cover the great deep.”

Cooper himself had only two years of formal education before starting work. He was a tinkerer and inventor, and in 1921 he opened a glue factory near Kips Bay. His company grew to become the largest supplier of glues and cement in the tri-state area, and they also invented a new form of gelatin that was instant. He sold the patents to another company who made it into the product we know today as Jell-O, a name conceived by Cooper’s wife, Sarah.

Cooper’s next venture was in the railroads. The railway was expanding to Maryland, so he bought land there hoping to capitalize on the new destination. We can imagine how pleasantly surprised he must have been to find iron ore on his land, making his investment especially profitable! When the steam train came across issues that were going to prevent it from reaching Maryland, Cooper realized he would need to become involved if he wanted to realize the full fruits of his Maryland land. He helped hack a steam train together from scrap parts, which became known as “Tom Thumb.” The launch of the steam train wasn’t all that smooth, but Cooper was able to prove its value and gain the people’s support. The project continued, built in part with the iron ore from Cooper’s land, and he became one of the richest men in New York.

In addition to being a savvy businessman, Cooper was also a philanthropist who knew the value of education. Together with his close friend and son-in-law, Abram Hewitt, he started Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art as a co-ed school that treated women equally to men. The credo behind the school has always been that education should be “as free as air and water,” and it remained tuition-free until 2013. Today the future of the school is unclear as the endowment has been drawn down and the school recently started charging tuition.

The architecture of the building has some notable history. Built in 1859, it used steel railroad tracks for support, making it the first steel reinforced skyscraper and the tallest building in New York at seven stories. Cooper knew that elevators would eventually be invented, so he prepared by including an elevator shaft that would be ready to install the new technology as soon as it was available. However, he thought elevators would be round rather than square, which has caused perpetual mechanical issues. The building was gutted in the 1970s, and everything except for the problematic round elevator shaft was removed, which you can see on the roof.

At the time, the building housed the largest underground hall in the eastern US, and Lincoln gave a speech here while campaigning in 1860. He spoke for five hours, but the content can be summarized into the three words “right makes might.” The two things he attributed to winning the election were the new medium of the photograph, and his speech at Cooper Union. Other presidents have continued the tradition of speaking here, most recently Barack Obama in 150 years after Lincoln.

The campus today fits snugly into the neighborhood with both the original building and the more modern one across the street. The statue of Peter Cooper in the park used to be cleaned by Jackson Pollock when he worked as a stone cutter at the Emergency Relief Bureau, who later lived nearby at 76 Houston St. And the school has produced many graduates that have helped shaped the city and the world, including Robert Maynicke, who designed the Germania Bank Building at 190 Bowery, and photographer Jay Maisel, who lives there today.

| 1859 | Cooper Union founded by Peter Cooper |

| 1860 | Abraham Lincoln delivers groundbreaking speech at Cooper Union's Great Hall |

| 1961 | Foundation Building declared a National Historic Landmark |

| 1965 | Foundation Building declared a New York City landmark |

| 1974 | Foundation Building's interior undergoes dramatic modernist renovation |

| 2002 | Foundation Building rededicated after renovation of brownstone exterior |

| 2013 | Cooper Union starts charging tuition |

| link | Cooper Union Official Website |

| internal | Cooper Union - Wiki |

| link | NY Curbed: Cooper Union |

| internal | Peter Cooper - Wiki |

| link | The Cooper Archives: Foundation Building |

| internal | gDoc |

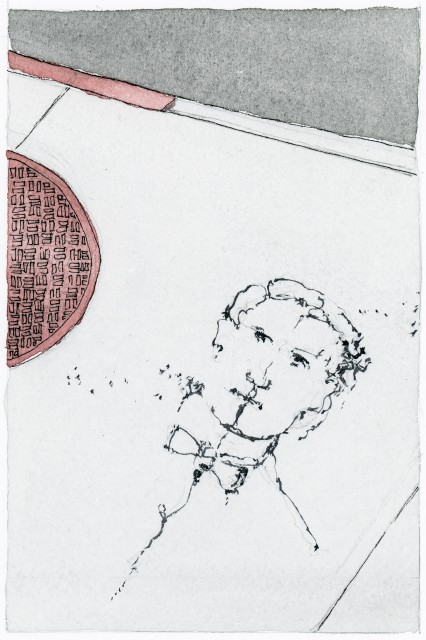

Paul Richard is a multidisciplinary artist, known for his rich, detailed oil portraits—like the one of Judge Marie M. Lambert hanging in New York Surrogate’s Court—as much as his “Designated Art,” where he places museum-style plaques on everyday street items, such as a fire hydrant, sometimes even adding a price tag.

One of Richard’s most lasting series is the drip paintings, which can be found in parts of Manhattan and Brooklyn. This one, a portrait of himself at the northeast corner of Spring and Elizabeth Streets, was created like the others: with a small can of black paint, Richard skillfully and quickly drips the shape onto the sidewalk.

Richard believes that art should be accessible. He appreciates that the sidewalks have larger audiences than the galleries, even if most of the people walking over his art every day hardly notice it—or if they do, they don’t know who made it. Richard’s unconventional approach doesn’t stop at the sidewalk, he once received permission from the manager of the Astor Place Kmart to do a show involving portraits of the employees, and it was up within days. Unimaginable in the gallery world where putting up a show takes years.

And Richard has a keen eye for the ironic. He once hung a “For Sale” sign on Boston’s Museum of Contemporary Art, and much of his art plays on the fact that it is technically graffiti. He has posted large boards on blank walls with the message, “Please No Graffiti On This Wall. Thank You, Paul Richard.” And when a Shephard Fairey commissioned mural at the Houston Bowery Wall was completed, he hung large white signs—one stated “Please No Graffiti”—directly on the mural discouraging others from defacing the wall, even though his own signs technically did just that.

| link | Paul Richard's Website |

| article | Paul Richard |

| link | Street Museum of Art: Paul Richard |

| link | Paul Richard: Taking street art to another level |

| link | Paul Richard Street Art |

| internal | gDoc |

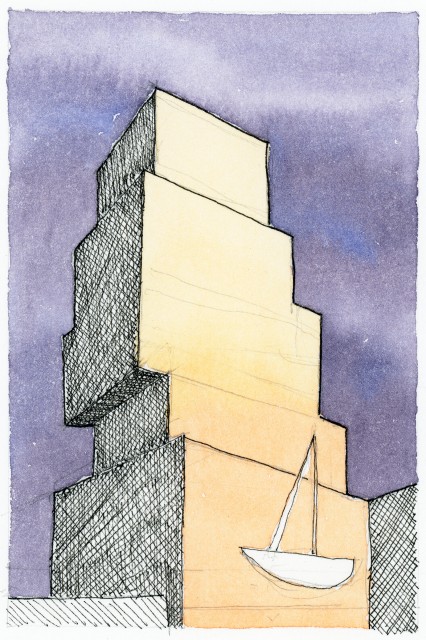

The tall, silvery building that stands out on the Bowery is the New Museum, which is the only museum in New York devoted to international contemporary art. Although the museum itself opened in 1977 in the tonier area of NYC on Fifth Avenue, this building was commissioned in 2002 with a Japanese design firm. At first the architects were surprised at the location, but the Bowery has always accepted those who didn’t quite fit in—and that is an appropriate setting for a museum that was founded in order to create a home for modern art that pushes traditional boundaries.

The building uses elements of its surroundings but with new interpretations to create a sense of orderliness that still fits in with a busy, rebellious neighborhood. Some say it looks like stacked boxes; other see the cityscape turned on its side. The texture of the neighboring buildings is brick, and the New Museum uses a perforated metal mesh which mimics the roughness, unlike many modern, smooth, glass buildings. In 2008, Condé Nast named the building one of the Architectural New Seven Wonders of the World.

The piece of art on the front rotates regularly, which, in turn, changes the the building itself. The stacked, shifting boxes create open, fluid, and light-filled interior spaces. They vary in height and are all free of columns. The large unobstructed spaces are built to hold large scale installations and sculptures, such as one of the more interactive exhibits which involved a slide going between two of the floors.

When Marcia Tucker created the museum in 1977, she had left a post as a curator at the Whitney. She felt that newer works from living artists seemed more difficult to place within the confines of traditional art, and she wanted to change that. The exhibits chosen for display here push the boundaries of conventionality in art—in much the same way that the building in front of us tests what we expect to see from a traditional museum.

| 1977 | New Museum founded by Marcia Tucker |

| 2007 | Moved from 5th Avenue location to 235 Bowery |

| internal | New Museum - Wiki |

| link | New Museum Official Website |

| internal | gDoc |

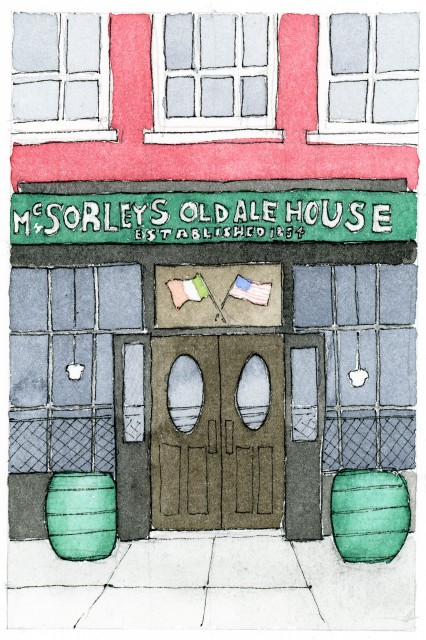

Inside New York’s oldest Irish tavern, McSorley’s Old Ale House, the aged look, abundant memorabilia, and sawdust floors that sop up spilled beer will get you feeling reminiscent of “Olde New York.” The owners maintain a strict policy against removing wall decorations in order to preserve the eclectic collection, which includes Houdini’s handcuffs, various historic posters (including an ironic “wanted” poster for John Wilkes Booth considering President Lincoln famously patronized the pub following his iconic and successful Cooper Union Address), and lucky wishbones hung by WWI soldiers pre-deployment, to be removed upon their return. Those still hanging memorialize the soldiers who were killed in action. In 2011 the bones gathered so much dust that the Health Department forced the reluctant owners to start routinely cleaning them.

McSorley’s operated as a “Men Only” pub, until a 1970 lawsuit mandated them to start admitting women. Such legal incidents signal everlasting conflicts between “Old” and “New” New York, and beg controversial questions about the validity of historic preservation.

Despite its modern role in the fabric of the East Village bar scene, McSorley’s is still known as a popular gathering place for artists and revolutionaries. Throughout the years it quenched the thirst of E. E. Cummings, Abraham Lincoln, John Lennon, and Woody Guthrie. It’s the last official stop on the Art Walk, and is a fine place to rest, reminisce, and discuss the tour.

| 1854 | John McSorley opens McSorley's Old Ale House |

| 1865 | Building becomes 5-floor tenement and McSorley family moves to 2nd floor |

| 1888 | John McSorley purchases building and becomes its landlord |

| 1910 | John McSorley dies, leaves Ale House to son Bill |

| 1911 | Bill McSorley converts Ale House to shrine for his deceased father |

| 1925 | e.e. cummings publishes "Sitting in McSorley's" |

| 1970 | McSorley's starts admitting women after lawsuit |

| link | McSorley's Old Ale House Official Website |

| link | NY Curbed: McSorley's Old Ale House |

| internal | McSorley's Old Ale House - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

57 Great Jones is another place—like the Sunshine Hotel and Amato Opera—that is easily missed, a graffiti-tagged building that still stands despite the constant change going on around it. Originally constructed as a stable around the time of the Civil War, it was converted to a saloon and dance hall by the 1900s. That rowdy vibe must have lingered in the building when Andy Warhol bought it in 1970 because a few years later he rented out a studio and apartment to Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was known for his outgoing personality and partying lifestyle almost as much as his expressive art. Basquiat lived and even died in this building, and his legacy remains. Until recently, his initials could be seen on the mail slot, and references to his work can sometimes be found in the ever-changing graffiti.

Basquiat, who was originally from Brooklyn, dropped out of high school in the early 1970s and briefly worked as an electrician. he despised the way his well of clients treated him, so he left and tried to make ends meet by selling his art on t-shirts and postcards. He came from Haitian heritage, and he felt that the art world of the time was elitist and exclusively white males. His response was expressive and bold, casual seeming but poignantly smart work with loud colors and an in-your-face attitude.

During this time, he was also graffiting tags around the city, and that led to one of his most more famous acronyms. Anyone around New York in the 1970s would have seen the mark of Basquiat and his friend Al Diaz, SAMO (pronounced “same-oh”), tagged throughout lower Manhattan. While getting stoned one day, they came up with the word, short for “same old shit,” which started a reference to what they had been smoking but quickly grew into a statement on racism in art and society in general. In today’s terms, SAMO became somewhat of a graffiti hashtag, often followed by a commentary on a complaisant society such as “SAMO© SAVES IDIOTS AND GONZOIDS…”—and yes, the copyright symbol was usually included as well.

By the end of the 1970s, Basquiat and Diaz had a falling out, and the SAMO tags became “SAMO IS DEAD.” Shortly after, in the early 1980s, Basquiat broke through as a solo artist.

During this time, Basquiat hung out with a notorious crowd. He dated Madonna for a period and frequently partied with other artist colleagues and celebrities. He was a hard drug user and despite attempts in Hawaii to get clean, he overdosed at 57 Great Jones in 1988 at the age of 27. His girlfriend found him, and together with a friend they dragged him to the sidewalk. They called the ambulance, but it didn’t make it in time. The fatal concoction had been a speedball, a mixture of heroin and cocaine that also claimed the lives of Chris Farley, John Belushi, River Phoenix, and Philip Seymour Hoffman. Basquiat is buried in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.

| 1970 | Housed bohemian Soho artists |

| 1983 | Andy Warhol rents out studio space to Jean-Michel Basquiat |

| 1988 | Jean-Michel Basquiat dies here of accidental drug overdose |

| 1960 | On December 22 Basquiat is born in Brooklyn |

This rather indistinctive luxury apartment building on the corner of Houston and Avenue A hides some remarkable features. To start, it was built by one of the East Village’s most notable characters, self-described “radical socialist turned real estate developer” Michael Rosen. Rosen grew up in Vermont, spent time on a kibbutz in Israel, and moved to New York City in 1983 as a junior professor of radical sociology at NYU. After a few years (and an unclear path), he ended up moving into real estate development. Red Square was one of his early ventures.

The dichotomy of Rosen is that he is both an active businessman and a well regarded social activist. Over the years, he has founded a Wall Street firm and served as CEO of a public company (whose offices were destroyed in the September 11 attacks). He developed this building and called it Red Square, mainly because it is red and it is square-shaped. But the statue on the roof? That’s Vladimir Lenin, direct from what was the USSR at the time of its manufacture. The way he is positioned has him enigmatically saluting Wall Street.

An avid supporter of the arts, Rosen brings that passion to the building. The lobby contains a large Julie Dermansky piece consisting of sea creatures carved into black steel panels, and the elevators are full of colorful animal mosaics by Claudia Nagy. In addition to the statue of Lenin, the rooftop contains the “Askew Clock” with jumbled numbers. The clock was created by accomplished graphic designer Tibor Kalman, a Hungarian immigrant who managed Colors magazine for several years.

Rosen’s influence in the neighborhood goes well beyond Red Square. He started a non-profit to preserve the East Village and essentially protect it from greedy developers‒yet critics point out that Red Square takes on the type of chain stores that the coalition discourages. A little older and more experienced, Rosen has said he now feels zoning laws never should have allowed a building as tall as Red Square to be put in this neighborhood.

Rosen himself lives in a luxury building in the area. While raising two boys they had adopted, he and his wife also unofficially took in five of the boys’ friends from the surrounding project housing, monitoring their education and sheltering them from the violence they had grown up with. Now mostly grown, the boys all consider the Rosens family. Rosen is considered a respected community activist who has also built subsidized housing and constructed halfway houses for victims of domestic violence.

Like the properties of Tony Goldman, Red Square is an example of how a developer can bring art, curiosity, and a little quirkiness to a neighborhood. Michael Rosen continues to be active in the East Village community.

| 1989 | Red Square Building constructed |

| 1994 | Lenin statue installed on roof |

| link | Forgotten New York: Red Square |

| article | Michael Rosen Fights Back After East Village Rezoning |

| article | Moscow on Houston St. |

| internal | gDoc |

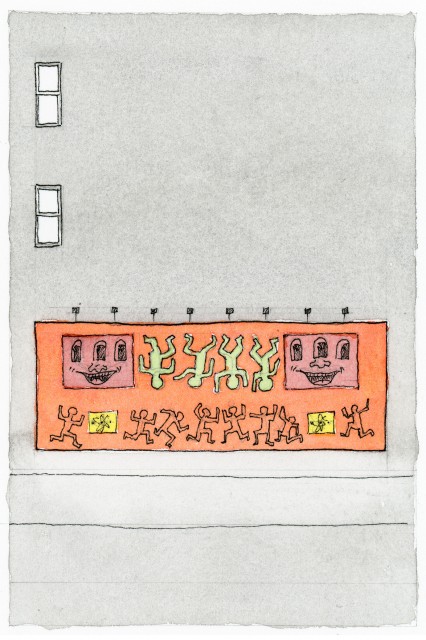

This old handball court wall is what launched Keith Haring to into public fame, and in turn, Haring indirectly made this wall into the renowned mural canvas it is today. In 1982, he and friend Juan Dubose figured that they could paint a mural on the trash-filled wall because no one would question their motives as long as they cleaned up the space. So they moved out all the trash, moved in the paint, and changed a neighborhood eyesore into a large orange wall filled with Haring’s signature cartoonish figures in motion.

Within a few months the wall had returned to being graffitied. By a turn of fate, Goldman Properties bought the land in 1984, which was run by patron of the arts, Tony Goldman. Not much was done with the wall until 2008, when, in honor of what would have been Haring’s 50th birthday, Goldman worked with gallery founder Jeffrey Deitch to commission a recreation of Haring’s original mural.

Haring was an artist of the 1980s, creating several public works throughout the decade. At first glance his art seemed cartoonish, but it often dealt with existential themes of sexuality, war, birth, and death. Haring died in 1990 at only 31 of AIDS-related complications.

Haring was a mentor to Angel Ortiz, a street artist several years his junior but whom he treated like an equal. This relationship came into play with Goldman’s 2008 mural, which opened to a great reception. However, within days it had been altered: Ortiz, had come overnight to add his own touches. Without painting over any of the art, he filled in the negative space with his own curvy lines and tags. Due partly to his relationship with Haring and possibly to the thoughtfulness of his addition, it also received a warm reception.

Goldman Properties still manages the art on the wall through a partnership with The Hole, a gallery run by former Deitch directors. Top contemporary artists from around the world are selected every few months, with a focus on street artists. After the Haring recreation, artists such as Os Gemeos, Barry McGee, and Kenny Scharf have all painted their own murals on this wall. Shepard Fairey’s contribution, May Day, earned the record as the most tagged-over installation.

This wall tells the story of what could have been an overlooked blemish in the neighborhood. But through the creativity of an artist and the vision of a dedicated developer, it has become a cornerstone of the area.

| 1982 | Keith Haring & Juan Dubose create infamous mural |

| 2008 | Bowery Mural Project established |

| tidbit | Tony Goldman |

| tidbit | Keith Haring |

| link | Goldman Properties: Houston Bowery Wall |

| link | Arrested Motion: Bowery Houston Mural |

| article | Little Angel Was Here: A Keith Haring Collaborator Makes His Mark |

| internal | Bowery Mural - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

This run-down building at 319 Bowery hides a romantic history. Anthony and Sally Amato ran their opera company from here for more than four decades before it closed in 2009, earning recognition as a great cultural institution in the city, influencing opera beyond New York and making it accessible to everyone.

After 26 years of existing as a mostly transitory company, the Opera moved into this 19th-century building in 1964. By fascinating coincidence, its was just a couple doors down from CBGB’s, the club that is considered the unofficial birthplace of punk music. When they moved in, the venue was cozy—it had just 107 seats, a 20-foot (6-meter) stage, and a tiny orchestra pit. This intimacy was important to the Amatos as it brought people closer to the operas and made the art feel more accessible.

Tony immigrated with his family from Italy to New York, and for years he managed his father’s restaurant and butcher market. But he was passionate about opera, and after closing shop for the day he would run to the local maestro to learn from him. He eventually left the butcher business to take a job with the American Theater Wing (the organization that produces the Tony Awards). While running workshops there, he noticed servicemen in his classes who didn’t know what to do now that they had rejoined civilian life. He wanted to provide a place for them to perform.

That sense of community was key to the Amato Opera company. They believed that tickets should always be affordable to the masses, which made them only $1.84 in the 1960s and $35 in 2008. They also held Opera-in-Brief for children to introduce them to the art. Tony was known for treating everyone with kindness, even the people he would find sleeping on the doorstep of the Amato.

He and Sally bootstrapped the operation and took on many of the roles themselves. He was the artistic director. They both performed. She made costumes and ran the box office; he managed the lighting, did publicity, and handled the business matters. It was a cultural institution that received commendations and awards from several mayors and was inducted into the City Lore’s Peoples’ Hall of Fame.

Tony and Sally had success in a very tough business, and not just in the sense that they were able to do what they loved for a living. Their passion for opera brought the high-end art to the public, and their mark on New York—and opera everywhere—is enduring. Sally died in 2000, and Tony continued to run the company until 2009, when he finally sold it because it reminded him too much of his wife. He passed away in 2011 at the age of 91.

In 2001, PBS made a documentary about the Amatos, and shortly before his death Tony published his own book called “The Smallest Grand Opera in the World.” Many people started their careers in opera here, and members went on to establish three new opera companies.

| 1948 | Amato Opera established |

| 1964 | Moved to 319 Bowery |

| 2001 | PBS releases documentary "Amato: A Love Affair With Opera" |

| 2009 | Closed after last performance of "The Marriage of Figaro" |

| 2010 | Amato publishes book about the company called "The Smallest Grand Opera in the World" |

| link | Curbed: Amato Opera |

| link | PBS - Amato: A Love Affair With Opera |

| article | Curtain Closing on New York's Amato Opera |

| internal | Amato Opera - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

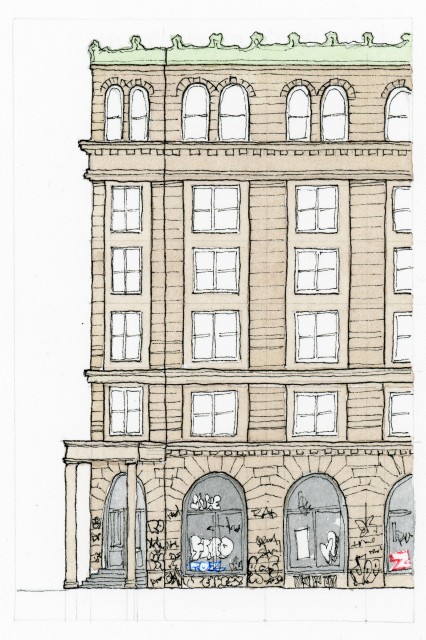

This abandoned-looking, graffiti-covered building at 190 Bowery belies an unexpected history. What started as a grand building for Germania Bank in 1898 eventually became one of the largest single family homes in Manhattan, which it remains today, despite the exterior that seems to say otherwise.

At the turn of the 20th century, the neighborhood was known as Little Germany, and the bank figured that would be a good place to base itself. Architect Robert Maynicke, a graduate of the Cooper Union just up the street, kept the renaissance revival style simple, clean, and strong to convey the stability of the institution. The granite facades, vault, and elevator still remain intact, and the building is fireproof. It cost $200,000 to build at the time, which is about $5.5 million today.

While the structure was solid, the neighborhood’s identity was not so much. Anti-German sentiment caused by World War I and the General Slocum Ship disaster dispersed the Little Germany community. The building was finally abandoned in 1961, riddled with trash, and used frequently as a loo.

Its fate changed in 1966 when photographer Jay Maisel, another Cooper Union graduate who was upset about a rent increase, visited a broker who had found housing for other artists. The broker showed him this 72-room, 6-storey building at 190 Bowery, and despite objections from his family, Maisel quickly raised the money to buy the place—$102,000, or just under $750,000 in today’s dollars.

He cleaned up the building, and in the late 1960s he rented the second and fourth floors to artists Adolph Gottlieb and Roy Lichtenstein, respectively. In 2005, the building was declared a New York City landmark, and in the 2008, New York Magazine called it “maybe the greatest real estate coup of all time,” estimating its worth up to $50 million.

At the time Maisel purchased the Germania Bank Building, he was best known for the photo of Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue” album cover. There was some controversy about this cover in 2010 when entrepreneur and artist Andy Baio used a pixelated version of the photo for a Kickstarter-funded album called “Kind of Bloop,” an 8-bit tribute to “Kind of Blue.” Maisel sued, and they ended up settling out of court with Baio paying Maisel $32,500 to use the art. The case raised questions about art appropriation and what rights an artist has when his or her original work is changed to create a new piece.

| 1899 | Construction finishes, building opens |

| 1966 | Jay Maisel buys building |

| 2005 | Designated a national landmark |

| link | The 72-Room Bohemian Dream House |

| link | Jay Maisel |

| link | German Traces NYC: Germania Bank |

| article | Kind of Screwed |

| internal | Germania Bank Building - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

| article | Bowery Boys: General Slocum Disaster 1904 |