7 Waves 4 Twenty Eight was designed by stereoscopic artist Gerald Marks for the 28th Street subway station on Park Avenue South. The mural is built into the glass blocks, which act as curved, cylindrical lenses. A series of lights and projectors behind the wall help to create an illusion of a 3-D art display. As one rides into the station, the fish and seaweed appear to move.

Marks began creating 3-D art in 1973. He is best known for the 3-D segments he directed for the Rolling Stones’ 1991 concert movie, At the Max.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Gerald Marks lecture |

| internal | 3-D Rolling Stones footage |

| internal | CultureNow |

In the early 20th century, sidewalks clocks were essential timekeepers for busy businessmen and effective advertisement for operating businesses. The gilded cast iron clock stands in front of 200 5th Avenue, the former Fifth Avenue Building. It was commissioned in 1909 by the company to replace a recently removed clock which stood in the same spot. The ornate piece was designed by Brooklyn-based Hecla Iron Works in 1909 and was modeled after the work of 16th Century Venetian architect Vioncenzo Scamozzi. It features classical ornamentation and a fluted Ionic column, and is considered to be one of the most impressive in the city.

In 1981, the clock became an NYC landmark. In 2011, Tiffany & Co. sponsered its full restoration.

| internal | The Magnificent 1909 Cast Iron Street Clock at 200 Fifth Avenue |

The Carlton Arms Hotel is also known as Artbreak Hotel or Ye Olde Carlton Arms Hotel. The 54-room, five-story building has been a hotel for most of its 100-odd years.

According to blueprints, there were originally two contiguous buildings put together at the beginning of the twentieth century when the hotel clientele were mostly farmers and business men from New Jersey and Connecticut looking for a hearty meal and place to sleep. They were able to keep their carriages and horses in a huge barn next door on 25th Street.

During Prohibition, the neighborhood was mostly Irish working class and the new elevated subway passed right in front on 3rd Avenue. The hotel lobby was converted into a speakeasy and big money card games were played in the rooms upstairs. Later on and with the opening of a few upscale neighborhood restaurants, The Carlton Arms became a respectable hotel — but not for long. In the ’50s the place started to turn sleazy, a hang out for drag queens, prostitutes and drug addicts. Like many of New York’s smaller, older hotels, The Carlton Arms became a single-room occupancy hotel during the ’60s and welfare recipients filled the place for more than 10 years.

After the hotel’s manager had a complete nervous breakdown in 1981, Ed Ryan, back in New York from ten years of world traveling, inherited the job. Ryan set out to break the cycle of despair-feeding-despair that had set in over the years of neglect. Vacated rooms were no longer re-rented to welfare tenants. Instead they were scrubbed, repainted, and refurnished for rent to travelers and transients who didn’t mind forgoing luxuries in exchange for a very low nightly rate.

Artists began to pass through the hotel and Ryan invited several of them to work at the front desk. In 1983, artist and front desk clerk Gil Dominguez painted a series of murals on the five-flight staircase. Later that year, he and fellow worker Colette Jennings began painting murals on small panels in several rooms. The art seemed a physical manifestation of the positive transformations possible within the old building. In 1984, Brian Damage, a downtown artist renowned for his beautifully executed installations at The Mudd Club, Studio 54, and Danceteria, began painting the “Submarine Room” and the idea for a complete artists’ transformation of the rooms took shape.

Today, every one of the 54 rooms, hallways, bathrooms and staircases are painted or decorated.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Art Nerd article |

| internal | Carlton Arms Hotel website |

| internal | YouTube Interview with Hotel employee |

| internal | NYPress Article |

| internal | Wikipedia My Little Margie |

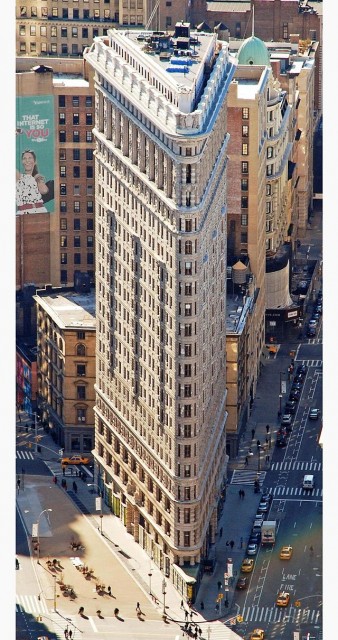

The distinctive triangular shape of the Flatiron Building, designed by Chicago architect Daniel Burnham and built in 1902, allowed it to fill the wedge-shaped property located at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Broadway. The building was intended to serve as offices for the George A. Fuller Company, a major Chicago contracting firm. At 22 stories and 307 feet, the Flatiron was never the city’s tallest building, but always one of its most dramatic-looking, and its popularity with photographers and artists has made it an enduring symbol of New York for more than a century.

Though the Flatiron Building is often said to have gotten its famous name from its similarity to a certain household appliance, the triangular region contained by Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and 22nd and 23rd Streets had in fact been known as the “Flat Iron” prior to the building’s construction. The brothers Samuel and Mott Newhouse, who made their fortune in the mines of the West, bought the property in 1899. At the time, efforts were being made to create a new business district in New York, north of the current hub of Wall Street. In 1901, the Newhouses joined a syndicate led by Harry S. Black, head of the George A. Fuller Company, and filed plans to build a 20-story building on the triangular plot.

The Flatiron Building would not be the tallest building in the city–the 29-story, 391-foot Park Row Building that had gone up in 1899 already held that spot. But its design by Daniel Burnham, a member of the prominent Chicago School of architecture, would make it one of the most unusual looking of the steel-framed skyscrapers being constructed at the time. (The first of these was the Home Insurance Building in Chicago, which had been completed in 1885.) Whereas many of the new tall buildings featured high towers emerging from heavy, block-like bases, Burnham’s tower soared directly up from street level, making an immediate and striking contrast against the lower buildings surrounding it.

This characteristic of the Flatiron Building’s design–its look of a freestanding tower–initially inspired widespread skepticism about whether it would actually be stable enough to survive. Some early critics referred to “Burnham’s Folly,” claiming that the combination of triangular shape and height would cause the building to fall down. Newspaper reports at the time of the building’s completion focused on the potentially dangerous wind-tunnel effect created by the triangular building at the intersection of two big streets.

Despite these critiques, crowds gathered around to gawk at the Flatiron Building when it was completed, and in the ensuing years it became a frequent sight in photographs, paintings and postcards and one of the most popular symbols of New York City itself.

Built around a skeleton of steel, the Flatiron Building is fronted with limestone and terra-cotta and designed in the Beaux-Arts style, featuring French and Italian Renaissance influences and other trends seen at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Shaped like a perfect right triangle, it measures only six feet across the narrow end.

The Fuller Company moved out of the building in 1929, and for years the area around the Flatiron Building remained relatively barren. Beginning in the late 1990s, however, the building’s enduring popularity helped drive the neighborhood’s transformation into a top destination for high-end restaurants, shopping and sightseeing. Today, the Flatiron Building mainly houses publishing businesses, in addition to a few shops on the ground floor.

via History Channel