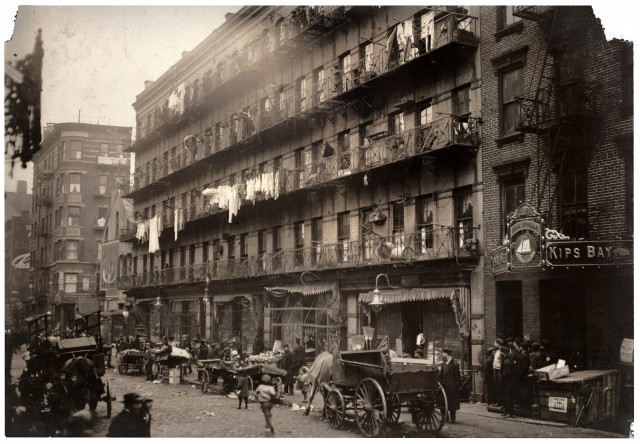

Jacob A. Riis was a social reformer and photojournalist in New York between 1873 and the early 1900s. A majority of immigrants who migrated to the United States in the late 1800s came from cultural backgrounds, particularly Eastern Europe, that New York did not initially welcome with open arms. Unlike other new immigrants, Riis’s Danish heritage was accepted. He immigrated to New York from Denmark in 1870 and moved to various places including Fordham, Buffalo, and even Pittsburgh for a short time. At one point, like many immigrants of the era, Riis lived in the impoverished conditions of the Lower East Side particularly on the Bowery. Riis’s cultural background and his ability to speak English gave him an advantage over other immigrants.

In 1873, Riis began began his career as a journalist and was a police reporter for The New York Tribune from 1877-1890. Riis saw photography as a method of persuasion and began photographing in 1888 to aid his argument that reform of the Lower East Side is necessary. He was particularly fond of the recent invention of flash photography which helped him to capture the naturally dark areas of tenement homes. Riis gave lectures on the issues within the Lower East Side utilizing lantern slides of images as support for his claims.

An editor of Scribner’s magazine attended his lecture at the Broadway Tabernacle and asked Riis to write an article to accompany the photographs. The article how “How the Other Half Lives” appeared in Scribner’s at Christmas 1889. The immense popularity of the article led to the publication of How the Other Half Lives in book form in late 1890 including Riis’s written account and his image converted to line drawings and halftone prints. Riis understood the citizens of the Lower East Side as victims of their harsh environment. This view is demonstrated in his photographs as they parallel the natural darkness of the tenement, it’s cramped and overcrowded space with saloons, crime, and parentless children. One particular image of a young boy holding a growler was enough to cause alarm amongst reformers and non-reformers alike. Riis attempted to persuade the elite to take action by describing how issues born in the Lower East Side such as crime and disease could eventually trickle their way uptown. Riis claims that disease could be transferred via clothing made for the upper class in the tenement sweatshops. The possibility of a class war where the Lower East Side rises up against the elite is also suggested in the text.

Throughout How the Other Half Lives, Riis refers several times to the horrid conditions found in the slums in “the Bend” on Mulberry Street. According to Riis, the inhumane conditions of the tenements is what breeds violence, disease, alcoholism, and immoral behavior. Riis determines that the only way to remove issues in the Lower East Side is remove the source of the problem: the tenement. Riis often promoted the building of parks and recreational areas for those living in the slums. Eventually, the tenements in “the Bend” were replaced by a park known as Columbus Park today.

In 1907, Riis moved to a farm in Barre, Massachusetts where he died in 1914. The architect and urban planner, Robert Moses, developed a beach for poor immigrants in 1936 at the western end of Rockaway, Brooklyn. The park was named was appropriately named Jacob Riis Park and nicknamed the “people’s beach.” Today, Jacob Riis is referred to by some as a pioneer in social documentary photography. The full archive of Riis’s photographs can be found at the Museum of the City of New York.

| sight | Columbus Park |

| tidbit | 1961 Zoning Ordinance |

Originally this park was the site of Mulberry Bend, one of the worst parts in the Five Points, the infamous intersection from the movie Gangs of New York. With multiple back alleyways such as Bandit’s Roost, Bottle Alley and Ragpickers Row. In 1897, due in part to the efforts of Danish photojournalist Jacob Riis, Mulberry Bend was demolished and turned into Mulberry Bend Park. The urban green space was designed by Calvert Vaux, co-designer of Central Park. In 1911 it was renamed Columbus Park.

Nowadays the park serves as meeting place for the Chinese community who play mahjong, perform traditional Chinese dances and music and practice tai chi in the early morning.

| tidbit | Jacob Riis |

| tidbit | 1961 Zoning Ordinance |

| wiki | Wikipedia |

| sight | NYC Parks |

| wiki | Five Points |

| wiki | Mulberry Bend |

| sight | Calvert Vaux |

The Manhattan Bridge is a two-decked suspension bridge that carries automobile, subway and pedestrian traffic over the East River. It connects Flatbush Avenue in Downtown Brooklyn with Canal Street in Chinatown, Manhattan. Because it was conceived after the Brooklyn and Williamsburg Bridges, it was called Bridge No. 3 in its planning phase. The bridge is distinguished by an elaborate stone portal and plaza at its Manhattan end.

The Manhattan Bridge has had a troubled existence from its birth. Hoping to relieve the enormous traffic over the Brooklyn Bridge, Gustov Lindenthal, Commissioner of the New York City Department of Bridges, proposed a steel wire suspension bridge over the East River in 1901. When this design was rejected for aesthetic reasons, Lindenthal came back with much debated plans for another version that featured four main cables made from chains of eye-bars, not steel wire. (Eye bars are flat 10-foot lengths of nickel-steel joined at their ends by steel pins. The arrangement is similar to a bicycle chain.) The cables were to be held aloft by two thin-profile steel towers.

A new mayor who came into office in 1904 appointed a new bridge commissioner, who, in turn, opted for another design, this one by Leon Moiseeiff. The new plan, also a suspension bridge, retained Lindenthal’s thin-profile towers, but rejected the eye-bar chain in favor of steel wire. Most crucial, Moisieff’s overall design relied on an experimental new bridge engineering principle called deflection theory. This theory held that the inherent structure of suspension bridges makes them stronger than was originally supposed; consequently, they did not require massive stiffening trusses like those used, for example, on the Williamsburg Bridge. Deflection theory would not be fully perfected for decades, and as a result, the Manhattan Bridge was, essentially, underbuilt.

Compounding the problem, Moisseiff placed the subway and streetcar lines — the streetcar tracks were replaced with auto lanes in the 1940s — on the outer edges of the roadway. The heavy moving loads of the trains put a twisting strain on the lightly reinforced deck, resulting in unending maintenance headaches. To correct the problems for good, a long-term reconstruction of the Manhattan Bridge was begun in the 1980s that has only recently ended, in 2007.

The Manhattan Bridge originally featured two of the most impressive entranceways of any New York City bridge. A stone archway styled after the Porte St. Denis in Paris and designed by of Carrere and Hastings (the architectural firm that designed the New York Public Library building) still serves as the Manhattan-side portal. The somewhat less grand Brooklyn approach, which included two statues by Daniel Chester French – allegorical figures of Brooklyn and Manhattan – was dismantled in the 1960s to facilitate traffic movement. The statues were moved to the Brooklyn Museum.

Second Lieutenant Benjamin Ralph Kimlau (1918-1944) was a Chinese-American bomber pilot who died serving his country in World War II. Born in Concord, Massachusetts, Kimlau moved to New York City with his parents when he was fourteen. After graduating from Dewitt Clinton High School in 1937, Kimlau first traveled to China, where he witnessed firsthand Japanese military aggression. The next year, he returned to the United States and entered the Pennsylvania Military College (now the United States Army War College). Kimlau graduated with honors, earning a commission as a second lieutenant in the United States Army Field Artillery.

Interested in airborne defense, Kimlau transferred from Field Artillery to the United States Army Air Force, and, following flight school, he was assigned to the “Flying Circus,” the 380th Bombardment Group of the Fifth Air Force in Australia. Beginning on February 27, 1944, along with four other pilots, Kimlau embarked on a mission to bomb Japanese airbases around New Guinea. On March 5, 1944, Kimlau and his fellow pilots were ordered to attack the Japanese rear line at Los Negros, an island adjacent to New Guinea. During the attack, the Japanese defenders shot down the attacking U. S. bombers, killing Kimlau and the other pilots. For their heroism and devotion to duty on this occasion and several others, the members of 380th Bombardment Group earned two Presidential Unit Citations.

The Lt. Kimlau Memorial monument was a gift of the Lt. B.R. Kimlau Chinese Memorial Post 1291, founded by Chinese-American World War II veterans in 1945. The post is the largest in New York City, promoting numerous patriotic programs and community service initiatives within Chinatown, such as petitioning the Department of Transportation for more traffic lights in Chinatown, establishing and contributing to a capital fund for the construction of a recreation center at the Chinese Community Center, publishing the American Legion’s first bilingual newsletter, offering a weekly Tai-chi class, as well as teaching new immigrants basic English. Located at the intersection of Oliver Street, East Broadway, the Bowery, and Park Row, Kimlau Square stands at the center of Chatham Square. In 1961, a local law named this island within Chatham Square in recognition of the contributions of Lt. Kimlau and the veterans post.

That year, the post erected this memorial, designed by architect Poy G. Lee. Standing at the head of Oliver Street, it is reminiscent of a triumphal arch. The memorial stands eighteen feet nine inches in height and is sixteen feet wide. Inscribed on the memorial is a dedication in both English and Chinese: “In Memory of the Americans of Chinese Ancestry who lost their Lives in Defense of Freedom and Democracy.” In June 2000, the post celebrated its 55th anniversary, which included a parade and a rededication of the Kimlau Memorial.

via NYC Parks

| sight | Kimlau Square |

Kehila Kedosha Janina is unique in that it is the only community of Romaniote Jews in the country and one of the last in the world. The Romaniotes are a group of Greek Jews who emigrated from the Northern Greek city of Janina. Unlike the Sephardi Jews, who lived more north in the Greek city of Selonica in Thessaloniki, the Romaniotes were living in Greece as early as the time of the Romans. While Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews speak Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian, Romaniotes speak Greek, eat Greek food, and hold other Greek customs. All but a handful of Romaniotes in Janina were killed in the Holocaust, leaving just 35 living Romaniotes in the city.

The Romaniotes immigrated to the Lower East Side in 1906 and established a congregation. In 1927, the Romaniotes built the Kehila Kedosha Janina synagogue at 280 Broome Street and formed a tight-knit community. Congregation members would stand at the docks at Ellis Island and bring newly-immigrated Romaniotes to join their community in the Lower East Side.

In 1999, the synagogue was added to the National Register of Historic Places and was designated a Historic National Landmark in 2004.

Kehila Kedosha Janina contiunes to hold traditional Romaniote services and also houses a museum dedicated to the history and culture of the 2,000-year-old Romaniote Community.

Since 2012, the Little Italy Street Art Project (LISA) has made it its mission to adorn the Lower East Side with fun and unique street art, creating the first mural district in downtown Manhattan. The Project began when LISA founder and curator Wayne Rada was working as a producer at the 2012 New York Comedy Festival. That year’s festival theme was humorous art, and Rada decided to recruit street artists for the event.

The team’s new murals around the neighborhood soon became a hit and received positive feedback from both the media and the community, and the street art project took on a life of its own.

LISA supports local businesses by buying supplies and paint from neighborhood stores, and creating merchants websites, promoting a sense of community and beautifying the streets of the Lower East Side.

| link | LISA Project |

| internal | The L.I.S.A Project NYC Brings Street Art to Manhattan’s Little Italy |

The California Gold Rush attracted thousands of men looking for work from Australia, Europe, Latin America, and Asia to the American West Coast in the 1840s and 50s. The growing Asian community in San Francisco soon caused racial tension, with Asian workers being accused of stealing the jobs of the white laborers who also settled there. In order to escape the violent discrimination against them, Asian workers began moving to the East Coast, where there were more job opportunities and more racial diversity. By 1880, the Lower East Side was home to a growing Chinese community.

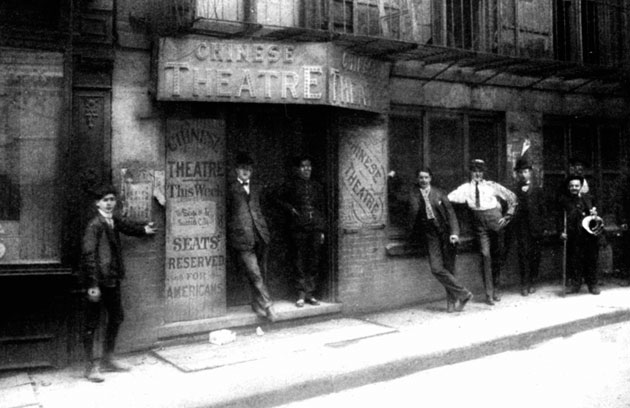

The Chinese Theater opened at 5-7 Doyers Street in 1893 as the first Chinese theater east of San Francisco. The theater hosted traditional Chinese performances and also featured murals by Loo Gop, Chinatown’s only Chinese illustrator at the time. Though the performances were entirely in Chinese, New Yorkers visited the theater and it soon became fashionable to attend shows there.

Chinatown in the early 20th century was riddled with crime and street gangs, and Doyers Street was often referred to as “The Bloody Angle” for its sharp 90-degree angle which enabled street gangs to attack victims by surprise.

In 1905, the Chinese Theater became the site of a violent shooting between the Hip Sing and On Leong street gangs. When the Hip Sings found out that Ah Foon, an actor and On Leong gang member, was using the Doyers Street Theater stage to taunt them, they began planning their revenge. One night in the middle of a packed theater the Hip Sings fired shots through the crowd, despite it being marked as neutral ground for the two gangs. Four On Leongs were killed in the attack.

The shooting was the work of Sai Wing Mock, famously known as Mock Duck. Duck was referred to by the media as the “Mayor of Chinatown” and was said to “strut around on Pell Street covered in diamonds.” The infamous gang leader was also known to wear a chain mail vest at all times in protection against the various attempts on his life. Because he knew that he would be blamed for the crime, he made sure to be at the police station at the time that the shooting was reported. At the station, Duck reported a gambling complaint (though a prominent leader of underground gambling himself) in order to secure his alibi at the station. Because he was at the station at the time of the shooting report, he could not be pinned with the crime.

In connection to the heightened gang activity in the area, there were also a series of underground tunnels beneath the theater and most of Chinatown. It is said that these tunnels were often used for moving illegal goods and for quick escapes from the police. Conveniently enough, the entrance to the tunnels was located right next to the theater at 5 Doyers Street. The tunnels may be how Mock Duck got from the theater to the police station so quickly when attempting to create an alibi for himself. The Hip Sings also most likely used the tunnels to flee the scene after the shooting.

This event, along with other gang violence, forced New Yorkers to question the safety of the area. As the neighborhood became more dangerous, theater attendance dwindled. The theater was forced to close in the early 1910s.

Today, a small part of the tunnels is now the Wing Fat Shopping Arcade, which houses dentist offices and other businesses. Unfortunately, most of the old tunnels are sealed off. The building that once held the old theater is now a clothing store.

| 1848 | California Gold Rush begins |

| 1880 | New York City's Chinese community begins to grow |

| 1883 | Chinese Theater at Doyers Street is opened |

| 1905 | Hip Sings gang shooting |

| internal | gDoc |

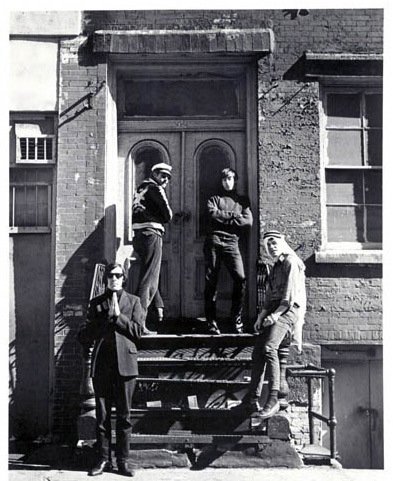

When the Lower East Side fell into disrepair in the 1960s, artists began taking advantage of the cheap old tenement buildings and started moving in. The building at 56 Ludlow Street became home to countless artists and musicians, and is most famously known as the birthplace for John Cale’s and Lou Reed’s Velvet Underground.

The 5th floor loft that Cale and filmmaker Tony Conrad moved into in 1964 cost $25 for the space–about $190 in today’s currency. In the winters, Cale and Conrad burned furniture and crates in their fireplace for heat and lived off of milkshakes and canned soup.

Cale met Lou Reed in 1964 at Pickwick Records in Queens. The two soon began playing and writing music together at Cale’s Ludlow apartment and recorded some of the earliest demos of the songs that would appear on the Velvet Underground’s debut album, The Velvet Underground & Nico. Despite rumors, Reed never moved into the apartment, according to Cale, he commuted every day to the apartment from his parents’ house on Long Island.

The group went by a number of different names such as The Warlocks and The Falling Spikes, but eventually changed their name to The Velvet Underground after an S&M novel of the same name that Tony Conrad found on the street. Cale thought it was the perfect name for the band, saying that there was nothing velvet about the situations they found themselves in.

Paul Morrissey, film director and Andy Warhol’s film caster, first saw the Velvet Underground perform at Cafe Bizarre (which was located on West 3rd) in 1965. Morrissey then told Warhol about the band and convinced him to manage them. After Warhol saw them play at Cafe Bizarre, he offered them his Factory as a rehearsal space, and they took him up on his offer. Morrissey then brought in German singer and model, Nico, to be the band’s new singer, saying that Lou Reed was an awkward performer. Together, Lou Reed, John Cale, Nico, Mo Tucker, and Sterling Morrison began recording their break-through 1967 album.

Though Warhol is credited as the album’s producer in the record’s liner notes, he merely paid for the band’s recording sessions. He also created the album’s iconic banana image, a cover that Rolling Stone magazine ranked as the 13th greatest album cover of all time. The original album pressings featured a peelable banana sticker, which hid a light pink unpeeled banana. Because of the expense of the hand-applied stickers, however, the peelable covers were soon replaced with a printed banana image.

Warhol continued working with the Velvet Underground until 1968. Along with designing the album cover for the band’s second album, White Light/White Heat, he also worked with the Velvets on the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, an art show that featured the band performing while images were projected and flashed onto the band.

| 1964 | John Cale and Tony Conrad move in |

| 1964 | Cale meets Lou Reed |

| 1965 | Paul Morrissey convinces Andy Warhol to manage The Velvet Underground |

| 1967 | "The Velvet Underground & Nico" is released |

| sight | Andy Warhol's Silver Factory |

| internal | gDoc |

| article | WSJ: Incubator for the Velvet Underground |

The Seward Park Branch of the New York Public Library opened on November 11, 1909 as one of the twenty public libraries Andrew Carnegie built throughout Manhattan. The Renaissance Revival structure, which was designed by the architectural firm of Babb, Cook & Welch was the most expensive Carnegie library constructed in the city.

With his new libraries Carnegie aimed to design to distinct structures, which was a new concept at the turn of the 20th century when most libraries were located in other buildings. The libraries were meant to serve as important social and educational fixtures in the neighborhoods in which they were located. In its first decades, the Seward Park Library served the neighborhood’s vibrant and thriving Jewish community. Today, the library serves a mixed neighborhood of Asian Americans, Jews, Hispanics, African-Americans.

The library become a New York City Landmark in 2013 and continues to operate as part of the New York Public Library.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | NYPL: Seward Park Library |

| internal | Google Books: Aguilar Free Library Society |

| internal | Historic Districts Council |

| article | FOLES: Seward Park Library |

The Lower East Side is known for its tenements, long history of immigration, and rapidly changing demographics. The area south of Delancey Street has undergone various cultural transformations and shifts in demographics, resulting in a highly unique and culturally diverse community. On this tour, we will explore the neighborhood’s rich history.

Throughout the 18th century, the area between present-day Division Street and Houston Street served as New York Governor and chief justice James De Lancey’s 399-acre farm. Remnants of his farm can still be seen today, from Orchard Street–where De Lancey’s famous cherry orchard was located–to Delancey Street, named after the Governor himself. During the American Revolution of 1775, De Lancey’s land was confiscated and he and his family were exiled from the city for supporting the English monarchy. The state then subdivided the land for purchase.

The Lower East Side’s population began steadily growing, with the help of a wave of Irish, German, and English immigrants. Between 1820 and 1840, the city’s population grew from 123,00 to over 310,000. 1848 saw the rise of Little Germany, which had a population of over 50,000. While the area was almost entirely German during the mid and late 19th century, Chinese, Italian, and Russian and Polish Jews also began calling the area home.

1904 marked the end of Little Germany, when the General Slocum passenger ship carrying New York’s most elite German families caught fire and killed 1,021 people. After the disaster, Little Germany almost completely disappeared. With most of the neighborhood’s prominent settlers dead, the remaining members of the community moved uptown. As the Germans moved out, the Lower East Side’s Jewish community began to thrive. German churches were converted into synagogues, and Jewish businesses began opening. Throughout the onsets of World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II, the neighborhood remained predominantly Jewish.

After World War II, blacks and Puerto Ricans began replacing Jewish residents, and by the 1950s, the Lower East Side became known for its street gangs and crime. By the 1960s, the Lower East Side was considered one of the most undesirable neighborhoods in the city. The old, run-down tenements were soon rented out by musicians and artists who used them as home and studio spaces. Students were also attracted by the area’s cheap grit and began moving into the area in the ‘70s.

As the city began focusing on the professional service sector and on building improvements in the 1980s and 90s, the price of housing in the Lower East Side began to rise, eradicating low-income housing. Today, the area’s popularity continues to grow and is now home to upscale boutiques, art galleries, and condos.

| internal | gDoc |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | Lower East Side History |

Loew’s Canal Street Theater opened in Lower East Side in 1927 at the height of the Golden Age of Cinema. The theater on Canal Street was designed by Thomas W. Lamb and held 2,300 seats, making it the second largest movie house in the city at the time of its opening.

As the population in the Lower East Side continued to grow, more and more movie houses began springing up in the neighborhood. By the early 20th century, the area held the densest concentration of movie houses in the nation.

Lower East Side native Marcus Loew came from a poor background, selling lemons and newspapers on the street. After working in various factories, he eventually became a furrier, where he met Adolph Zukor. Zukor, also a furrier, owned a slew of penny arcades–rooms full of hand-cranked games that cost just a penny to play–and Loew decided to buy into the business. He soon began opening arcades around the country. While opening a new arcade in Cincinnati, he was told of a competitor who was making more money with movie houses than Loew was making with his arcades. While in Cincinnati, Loew struck a deal with the Vitagraph Company, a Brooklyn-based movie studio, and set up a makeshift movie screening. At a nickel per ticket, Loew made $250 in one night alone.

When he returned to New York, Loew began converting his penny arcade spaces into movie houses, and started Loew’s Theater Chain in 1904. In order to increase the quality of movies at his theaters, he bought Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures, and Louis B. Mayer Productions in 1924 and merged them all to form MGM Studios, one of the most important film studios in the country.

After Loew’s death in 1927, the Loews Corporation continued opening movie houses around the country. Shortly after the Canal Street Theater opened in 1927, the company sold it to Greater M&S Circuit, but it eventually fell back into the Corporation’s hands after Greater M&S Circuit went bankrupt in 1929. In the 1950s, the theater began its decline and soon closed.

In the 1960s, the building’s lobby became retail space and its elaborate auditorium was converted into a warehouse. In 2010, there was talk of using the landmarked building as a performing arts center, but the plans fell through. The building owners also proposed to convert the space into a condo complex, but the NYC Department of Building denied the plan. Today, the theater’s lobby stands empty. The auditorium, however, still functions as a warehouse.

The Loew’s Corporation is now part of AMC Theaters.

| 1904 | Marcus Loew creates Loew's Theater Chain |

| 1924 | MGM Studios is formed |

| 1927 | Marcus Loew dies |

| 1927 | Canal Street Theater is built |

| 2006 | Loew's Corporation merges with AMC Theaters |

| 2010 | 54 Canal Street is landmarked |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Loew’s Canal Street Theatre |

| internal | Hidden Gem on Canal Street |

| internal | Inside The Abandoned Old Loew's Theatre On Canal Street |

| link | NYC and the Birth of the Movies Bowery Boys Podcast |

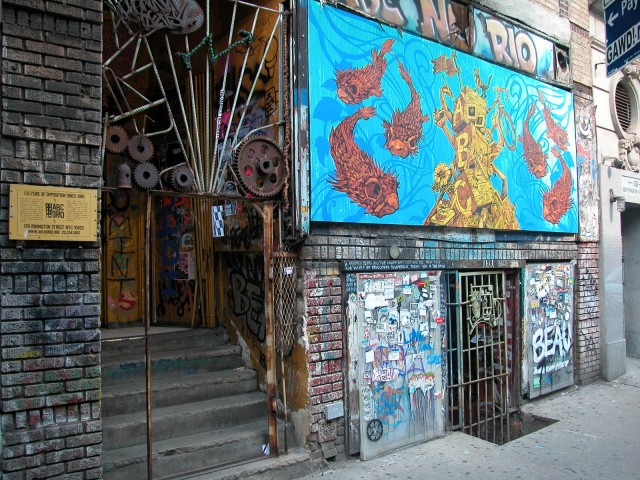

Beginning in the late 1960s, the Lower East Side of Manhattan was facing massive disinvestment by landlords, with up to 80% of the area’s housing stock abandoned and seized by the city’s government for non-payment of taxes by the late 1970s. The city’s land use policies at the time kept these buildings empty until the area again became attractive to developers and investors.

ABC No Rio grew out of the 1979 Real Estate Show, which was organized by Colab (Collaborative Projects), an artists’ group dedicated to fostering connections between artists and members of the community. The show aimed to criticize the city’s building policies, which ultimately kept artists – who wanted to put the abandoned buildings around the city to use–from buying them.

The show opened to the public on January 1, 1980 in an abandoned building at 123 Delancey Street and was shut down before the morning of January 2 by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development. In the following negotiations with HPD, the organizers of The Real Estate show were granted the use of the building at 156 Rivington Street, which became ABC No Rio. The name derives from the remaining letters of an effaced sign that was on the building: “Abogado Con Notario” (Lawyer with Notary).

The center features a gallery space, darkroom, and silscreening studio and hosts various radical projects in NYC, including the NYC Food Not Bombs collective. ABC No Rio acts as a community center for the Lower East Side, sponsoring benefits for the community and promoting “do it yourself volunteerism, art and activism.”

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | CultureNow page |

| wiki | Collaborative Projects |

First Shearith Israel Graveyard (also known as Chatham Square Cemetery) is a tiny graveyard at 55-57 St James Place. It is the oldest of three graveyards used by Congregation Shearith Israel, which is the oldest Jewish congregation in North America. The land was purchased in 1682 by Joseph Bueno de Mesquita.

During the American Revolution of 1775, the cemetery served as a strategic location for General George Washington, as it overlooked the East River. It was also used by the British when they conquered New York in 1776. It is said that British soldiers removed many of the lead epitaph plates in the cemetery in order to make bullets.

Along with war heroes, the cemetery also holds the remains of Jonas Judah, the first American-born Jew to enroll in medical school. When a yellow fever epidemic broke out in 1798, more than 2,000 New Yorkers died. In order to avoid contracting it, healthy residents moved out of the city to drier climates. Judah, a 3rd year medical student at King’s College (now Columbia University), decided to stay and provide medical attention to those who had contracted the disease. He died of yellow fever on September 15, 1798 when he was 20 years old.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Chatham Square Cemetery |

| internal | Jonas Judah |

This permanent public sculpture for Governor Smith Houses in New York’s Chinatown integrates sculpture and landscape elements with a symbolic message of international community.

The great circle route that connects China, the Caribbean and the Smith Houses is indicated by a 42 foot galvanized steel arrow pointing northwest.

The arrow passes through a sphere of six orbital rings of steel letters spelling out the names of the tenants’ places of origin.

via Hera Sculpture

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Hera Sculptures |

| internal | CultureNow article |

Sculpted by Taiwanese artist Liu Shih, the 15-foot bronze statute of Confucius, the Chinese philosopher, was presented by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in 1976 to commemorate the U.S. bicentennial. Its base holds an inscription of an American Flag, along with a Confucian proverb. The piece praises the US’s just government and its strong and wise leaders. The sculpture in front of the Confucius Plaza Apartments is one of the most frequently visited landmarks in Chinatown.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | Gifting Confucius |

The Mahayana Buddhist temple at 133 Canal Street is the largest Buddhist temple in New York City. It was founded by Annie Ying in 1997 after she noticed that all of the Buddhist temples in the Lower East Side were small storefronts and were not big enough to serve as proper temples.This was not Annie’s and her husband James’ first temple, however. In 1962, they founded the Eastern States Buddhist Temple of America Inc. at 64 Mott Street, which is the oldest Buddhist temple on the east coast.

Ying said that she founded the temples not only for religious purposes, but for social ones. She said that her main motivation was to give the elderly Chinese population a place to socialize and call home.

The Canal Street temple contains a golden statue of the Buddha sitting on a lotus. At 16 feet, it is one of the largest statues of Buddha in New York. Around the main hall are depictions of events in the Buddha’s life.

The temple’s exterior showcases various different Chinese architectural designs, such as the two large golden lions at the main doors which guard the temple from evil spirits. Traditionally, homes belonging to Chinese families are guarded by bronze or stone lions.

The Mahayana sect–one of the two primary schools of Buddhism–places more emphasis on the teachings of the Buddha, with its main goal being liberation and enlightenment of all conscious beings. Mandarin is the main language used in this temple.

Public services are held on weekends.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Macaulay site |

| internal | NY Magazine article |

The Gothic Revival structure at 60 Norfolk Street was built in 1850 as the Norfolk Street Baptist Church, but it soon became the home of the oldest orthodox congregation of Russian Jews in the United States, which was founded in 1852 and has occupied the building since 1885.

Rabbi Jacob Joseph, the first and only Chief Rabbi of New York City, led the congregation from 1888 to 1902. He emigrated from Lithuania in 1888 to unite the orthodox Ashkenazi community under a single leadership.

In 1967 Beth Hamedrash Hagadol was designated a New York City landmark after it was threatened with demolition. It was one of the first New York City synagogues to have received this honor and the first in Lower Manhattan.

In 2007, Rabbi Mendel Greenbaum made the decision to shut down the synagogue, as its congregation had dwindled to just 15 members. The building sat empty and abandoned for years. In 2012, Greenbaum filed an application to the Landmarks Preservation Department seeking to demolish the structure and replace it with condos, with room for a small synagogue on the ground floor. His plan was denied.

Today, the Lower East Side and New York City preservation communities are working to restore the building to its original splendor. Members of the Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy are leading the fight to generate support for the preservation and restoration of Beth Hemedrash Hagadol.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy |

| internal | Wikipedia |

The Eldridge Street Synagogue opened at 12 Eldridge Street in 1887 as one of the first synagogues erected in the US by Ashkenazi Jews. The structure was designed by architects Peter and Francis William Herter, brothers who received many commissions in the Lower East Side and incorporated Jewish designs, such as the stars of David, in their buildings, mainly tenements. When completed, writers raved about at Moorish Revival style chosen for the building, with its stained-glass windows, hand-stenciled walls, intricate brass fixtures, and 70-foot-high vaulted ceiling.

From its opening through the 1920s, thousands participated in the synagogue’s religious services, with police controlling the huge crowds on Jewish High Holidays. During this time, the synagogue also functioned as a center for acculturation. The synagogue fed the needy, helped residents secure loans, taught newcomers about job and housing opportunities, and helped make arrangements to care for the sick and dying.

For fifty years, the Eldridge Street Synagogue flourished, but membership began to dwindle as the Great Depression hit, immigration quotas were put in place, and as congregants moved to other areas of the city. From the 1930s on, the main sanctuary was used less and less, and by the 1950s, its leaking roof and unsound structure lead to its closing-off. Without the money and resources to maintain the sectuary, the congragation moved downstairs, worshipping in the more intimate house of study (Beth Midrash).

The main sanctuary remained empty for twenty-five years, from 1955 to 1980. In 1986 the not-for-profit Eldridge Street Project was founded to restore the synagogue and renew it with educational and cultural programs.

The Eldridge Street Synagogue was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1996.

On December 2, 2007, after 20 years of renovation work that cost $20 million, the Eldridge Street Project completed the restoration and opened to the public as the Museum at Eldridge Street. The museum offers tours that relate to American Jewish history, the history of the Lower East Side and immigration.

The building continues to function as a synagogue.

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | Eldridge Street website |

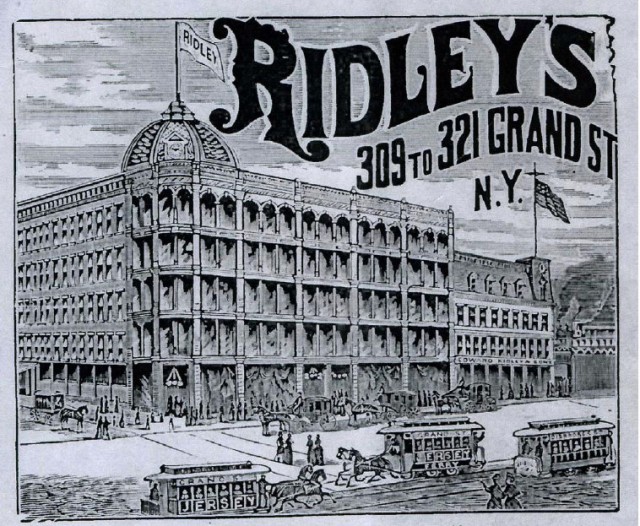

When Ridley & Sons opened in the Lower East Side in 1848, it was the largest department store in the neighborhood. The store’s business grew considerably, and eventually occupied about 20 lots along Allen and Orchard Streets. The properties at 66-68 Allen Street and 65 Orchard Street, which became New York City Landmarks in 2012, are the only surviving lots. The corner space wasn’t always painted pink, however. Sometime in the 1990s, Dorothy Goldman, the current building owner’s wife, thought that the pink paint would pep up the building’s “dreary” facade.

Edward Ridley, an English dry goods store owner, emigrated from England in the mid-1840s after he was forced to close his shop due to debt in 1843. He then opened a small dry goods store on Grand Street in 1848, which eventually grew into Ridley’s Department Store. The store became notorious for its cheap prices and quality products, and quickly became a Lower East Side staple. By 1880, Ridley’s was bringing in over $4 million (adjusted for inflation) in annual sales.

Before his death in 1883, Edward Ridley began planning another store expansion. Ridley died before the expansion and his sons Arthur and Edward, Jr. continued the plans. The cast iron buildings at 66-68 Allen Street and 65 Orchard Street were built and designed by architect Paul F. Schoen and completed in 1886.

By the 1890s, business began to decline. As the Asian population grew, neighborhood demographics began shifting and large department stores in the Lower East Side such as Lord & Taylor began moving uptown to 5th Avenue. Ridley’s planned to move uptown in 1900s, but it never did. The store finally closed in 1901.

The Ridley’s properties along Allen Street were not only the sites of buying and selling, however. 59-63 Allen Street–now a parking garage–was also the site of multiple mysterious murders.

After the store’s closure, Edward Ridley, Jr. opened a real estate business, which he ran out of a cellar of one of the old department store buildings. In 1931, Ridley’s assistant, Herman Moench, was found shot dead in the cellar. The case quickly went cold when the police were unable to come up with any suspects. After the murder, Ridley hired Lee Weinstein as his new assistant. Two years after Moench’s death, both Weinstein and Ridley were found dead in the same room where Monech was killed. Weinstein had been shot, and Ridley had been beaten to death. Ballistics tests showed that both assistants had been shot with the same gun!

After some investigation, police found a will, said to be Ridley’s, which entrusted $200,000 to Weinstein. It was soon found that the will was a forgery that was created by Weinstein and his two accomplices, who happened to be Ridley’s accountants. Police soon discovered that Weinstein had already stolen the $200,000 even before Ridley’s murder. Though Ridley’s accountants were indicted for the murders, there was no proof connecting them the incident. All three murders remain unsolved.

Both Edward Ridley, Jr. and Edward Ridley, Sr. are buried in Green-Wood cemetery in Brooklyn.

| 1848 | Ridley & Sons Department store opens |

| 1883 | Edward Ridley dies |

| 1886 | Lots at 66-68 Allen Street and 65 Orchard Street are completed |

| 1901 | Ridley's closes |

| 1931 | Herman Moench is killed |

| 1933 | Lee Weinstein and Edward Ridley, Jr. are found dead |

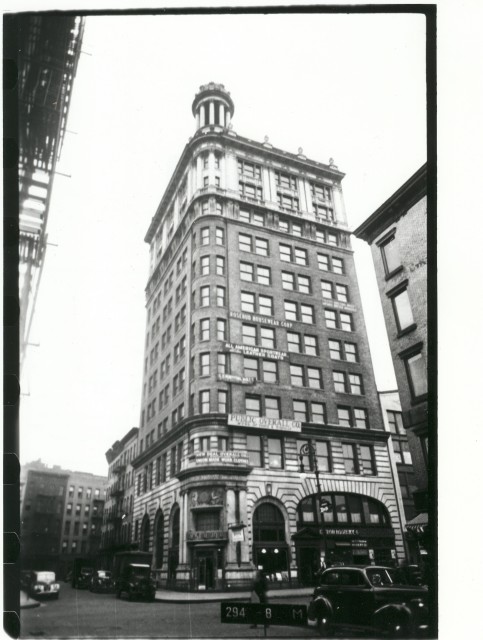

Russian-Polish immigrant Sender Jarmulowsky opened his bank at 54 Canal Street in 1873. The bank quickly became a staple in the Lower East Side, catering to the neighborhood’s large Jewish community. Residents could conduct transactions in Yiddish and even buy steerage tickets for their families back home. The Lower East Side community trusted Jarmulowsky, a respected philanthropic business owner, and felt comfortable opening accounts with him.

In 1911, the original bank building at 54 Canal Street was demolished, and a new modern building of Caen stone, a type of French limestone, replaced it. Jarmulowsky chose the sophisticated stone and bronze design to show the rest of the city that the Lower East Side was not a cut-off Jewish community, but one that was integrated into the American economy.

As the new Jarmulowsky Bank was being built, the headquarters of the Jewish Daily Forward, a Yiddish newspaper, was also on its way up. When Jarmulowsky saw that the Forward building–which was located just down the street at 175 East Broadway–was going to be slightly taller than his bank, he called for a last minute addition to the roof of his building. He had a 50-foot-tall circular, dome-like structure made of columns called a tempietto added to the corner point of the bank’s roof. The ornate addition made Jarmulowsky’s Bank the tallest building in the Lower East Side. The original tempietto was destroyed during renovation in 1990.

Only three weeks after the bank’s opening, Jarmulowsky died, leaving his sons in charge of the business. By 1917, however, the bank was forced to close. When World War I broke out in 1914, the bank closed in order to keep account holders from withdrawing their money and sending it overseas to their families in Europe. According to the New York Times, 2,000 people demonstrated in front of the bank because of the shutdown. Five hundred demonstrators then stormed the house where son Meyer Jarmulowsky lived, forcing him to escape across tenement rooftops. Jarmulowsky’s sons were soon indicted for banking fraud and mismanagement, and the bank closed.

After the closure, the state took possession of the bank in the 1920s and auctioned it off. The first floor was the site of various different banks over the years, with the rest of the building housing lofts and textile companies. In 2011, DLJ Real Estate Capital Partners began restoring the building and planned to rebuild the destroyed tempietto. In 2013, the building was slated for conversion into a luxury hotel.

| 1873 | Jarmulowsky Bank founded |

| 1911 | Original bank building demolished |

| 1912 | New bank building erected |

| 1914 | World War I begins |

| 1914 | Bank shuts down; demonstration |

| 2011 | DLJ Real Estate Capital Partners purchase building |

| 2013 | Building is slated for conversion to hotel |

Doyers Street in the early 20th century was notorious for its gang violence and brutal murders. The street’s sharp bend allowed the On Leong Tongs and Hip Sings–rival Chinese street gangs–to sneak up on their victims and attack without being seen. Some of these gang members struck with hatchets, giving birth to the phrase “hatchet man.”

In 1905, the Bloody Angle saw more gang violence at 5-7 Doyers Street, which was the sight of a Chinese opera house. One night during a performance, the Hip Sings opened fire on the On Leongs, killing four of them. This episode, however, was only one in a series of bloody disputes between the two gangs. Until 1913, the gangs chased each other through the Chinatown streets, murdering their rivals. The only thing that could stop the Tong Wars, as the attacks were called, was a truce mediated by the US and Chinese governments.

In 1994, law enforcement officials said that more people died violently at the Bloody Angle than at any other street intersection in the United States.

| sight | Chinese Theater on Doyers Street |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Wikipedia |

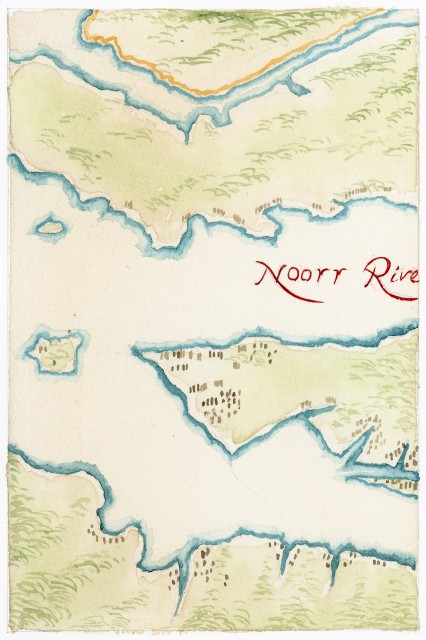

Created in 1639, the Manatus Map is the earliest known drawing of New York City. The full name, “Manatus Gelegen op de Noot Rivier,” or “Manatus located on the North River,” refers to the Dutch name for what is known today as the Hudson River. The map shows many individual farms and plantations, as well as both Conyne and Staten Eylandts. Exactly who drew it is still a mystery, but historians think it was likely the cartographer for the Prince of Nassau for the West India Company of Holland, Johannes Vingboons, or cartographer Joan Vinckeboons. Currently the map is housed at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

| 1639 | Johannes Vingboons draws Manatus Map |

| link | Library of Congress: Manatus Map |

| article | Interpreting the Little-Known Minuit Maps of c. 1630 |

| internal | Johannes Vingboons - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |