Originally called Liberty Plaza Park for its location beside One Liberty Plaza, Zuccotti Park is now most famously known for its role in the Occupy Wall Street protests in 2011. The space was originally created in 1968 by US Steel as a much-needed public space. The park underwent a series of renovations after it was heavily damaged after the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center in 2001. In 2006, the space was renamed Zuccotti Park after the chairman of Brookfield Office Properties, the company that currently owns the park.

Long before it was a park, the area was once the site of New York City’s very first coffee house called the King’s Arms. In 1696 John Hutchins bought the property and built a house called the King’s Arms. The two-storey-high building was made of brick imported from Holland and included an “observatory” on the roof where customers could enjoy their coffee and a view of the city.

The King’s Arms was built not long after the Dutch first imported coffee into New Amsterdam in 1668. Before coffee, Dutch settlers enjoyed beer with their breakfast. Coffee slowly began replacing beer as the go-to morning drink and became a hit within the homes of the settlers.

Coffee houses in Europe served as meeting places for politicians, businessmen, and even served as courthouses. This use also carried over to their American counterparts. According to records, the King’s Arms may have bene the only coffee house in the city–or the only one important enough to mention.

Owner John Hutchins was eventually arrested for speaking badly of King George, Great Britain’s ruling monarch at the time.

| wiki | Zuccotti Park |

| link | The History of Coffee in Old New York |

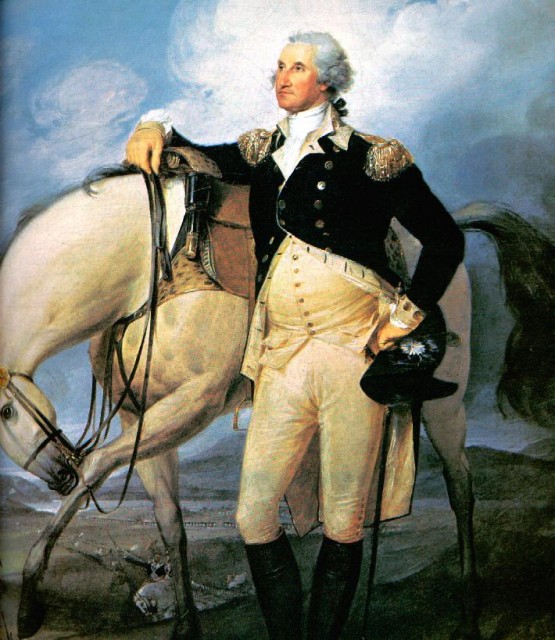

George Washington served as first President of the United States from 1789-1797, Commander of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War in 1775, and was one of the Founding Fathers of the country. Under his direction, the US Constitution–which remains the supreme law of the nation–was drafted.

Washington served two terms as President and was unanimously elected in both. He aimed to create a strong national government that remained neutral in European conflicts such as the French Revolutionary War and one that preserved liberty, promote commerce, reduce regional tensions, and promote American nationalism. Even during his lifetime, Washington was hailed as the father of his country,

Henry Lee, a Revolutionary War General, described the President as “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen” in the eulogy he gave at Washington’s funeral.

According to both the general public and scholars, Washington is ranked among the top three presidents of the United States alongside Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The former President remains an international symbol of nationalism, liberation, and revolution.

| 1731 | Washington is born in Virginia |

| 1775 | Becomes the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War |

| 1776 | The Patriots gain their independence from Britain under Washington's command; the United States of America is born |

| 1788 | US Constitution is ratified |

| 1789 | Elected as the first President of the United States |

| 1792 | Serves a second term as President |

| 1799 | Dies in Virginia |

| sight | Shearith Israel Graveyard |

| sight | St. Paul's Chapel |

| tidbit | The Great Fire of New York |

| tidbit | Manatus Map |

| sight | Fraunces Tavern |

| wiki | George Washington |

| link | Eulogy Given at the Funeral of George Washington |

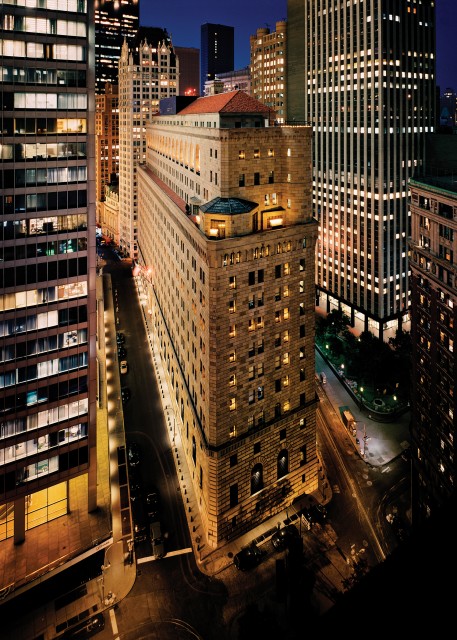

Who would think that the Italian Renaissance building at 33 Liberty Street held more gold than Fort Knox? Though built in 1919-1924, most of the Fed’s gold arrived during and after World War II when countries were trying to seek out the most secure location for their gold. Though it does not hold the 12,000 tons of gold that it once did, it holds 25% of the world’s gold reserves, making it the largest depository of gold in the world.

The infamous gold vaults lie 80 feet below street level and 50 feet below sea level. To ensure maximum security of the gold, two New York Fed gold vault staff members and one member from the New York Fed internal audit staff must be present anytime the vault is open, even to change a light bulb.

Despite these safety precautions, the vaults are open for free public tours.

| wiki | 33 Liberty Street |

| wiki | Federal Reserve Bank of New York |

| sight | Landmarks Preservation Commission |

| sight | About the Fed: Gold Vault |

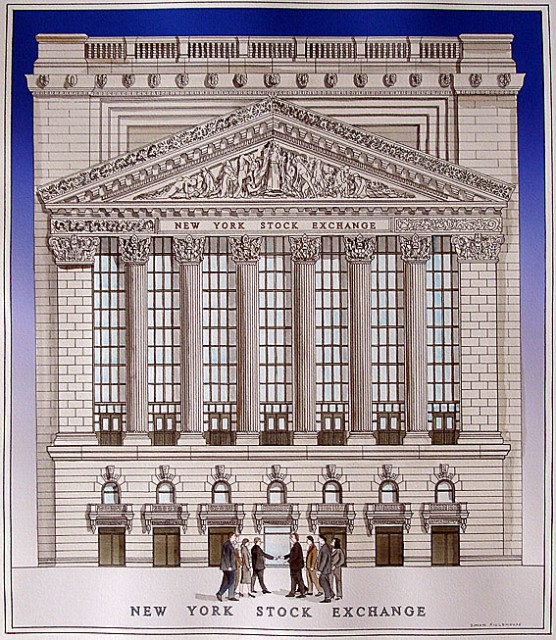

The infamous neo-classical New York Stock Exchange building at 18 Broad Street was designed by New York City architect George B. Post in 1903 and served as a replacement of the previous headquarters which stood in the same lot. The series of white statues on the building’s pediment were not added until 1908-09. The headquarters became a landmark in 1985.

The New York Stock Exchange was not always as glamorous as it is today, however. The NYSE can be traced as far back as 1792, when stock dealers and auctioneers met each day to discuss finances under an old Buttonwood Tree at 68 Wall Street. By the end of that year, the businessmen signed the Buttonwood Tree Agreement, which led to the formal organization of the New York Stock Exchange (originally named the New York Stock Exchange Board). By 1793, the Board had its first makeshift indoor headquarters at Tontine Coffee House at the corner of Wall and Water Streets. The headquarters moved around Wall Street several times before settling at 18 Broad Street.

The Exchange has survived a series of financial panics and crashes, the most notable at the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The shutdown lasted for four months and two weeks–the longest exchange shutdown in history.

Today, the NYSE is the largest stock exchange in the world.

| 1792 | Early stock dealers begin meeting to discuss finances |

| 1792 | Buttonwood Agreement is signed; New York Stock Exchange Board is formed |

| 1793 | NYSEB begins meeting in Tontine Coffee House |

| 1903 | George Post's new building replaces the old Stock Exchange headquarters |

| 1909 | Pediment statues are completed |

| 1914 | Longest stock exchange shutdown in history |

| 1985 | NYSE building becomes a landmark |

| tidbit | Ticker Tape Parades |

| wiki | New York Stock Exchange |

| wiki | Tontine Coffee House |

| sight | Landmarks Preservation Commission |

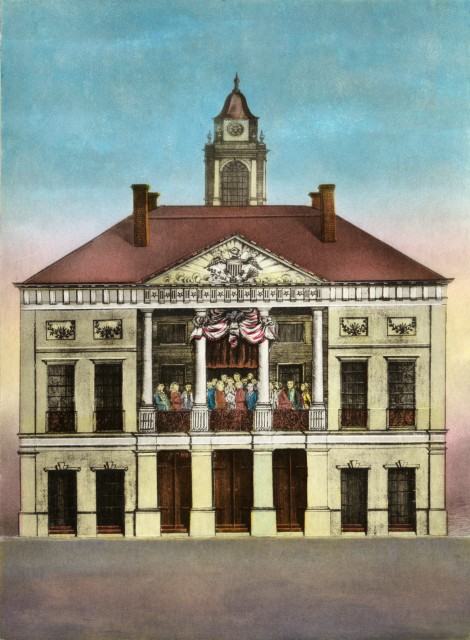

The original Federal Hall building at 26 Wall Street was the site of some of the most important events in the early history of the United States. When it was built in 1700, it served at New York’s second City Hall. It also was the site where newspaper publisher John Peter Zenger was tried and imprisoned for libel in 1735. His case helped to establish freedom of the press, which was later put in writing in the Bill of Rights in 1789.

Though the structure was the site of a host of important events such as where the Northwest Ordinance–which prohibited slavery in future states–was established, the most significant was George Washington’s inauguration in 1789. Federal Hall was the meeting place of the 1st Continental Congress in 1789, and the first thing they did was count the votes as Washington as the first President of the United States.

In 1812, this historic structure was demolished and replaced with the current building, which is one of the most exceptional examples of classical architecture in the city. Though the original building is gone, the original balcony floor and railing where Washington was inaugurated are on display inside. The current structure was designed by American sculptor and architect John Frazee and opened in 1842. The Doric columns and domed ceiling resemble the Greek Parthenon and the Roman Pantheon as tribute to Greek Democracy and to the Roman Republic.

The bronze statue of Washington that stands on the front steps was designed by John Quincy Adams Ward in 1882 and marked the approximate site where the President was inaugurated.

The Federal Hall Memorial became a New York City Landmark in 1965.

| 1700 | Federal Hall is built |

| 1735 | John Peter Zenger is tried for libel |

| 1787 | Northwest Ordinance is passed |

| 1789 | First Continental Congress meets in Federal Hall |

| 1789 | George Washington is inaugurated as first President of the US on Federal Hall balcony |

| 1812 | Original building is demolished and replaced with current structure |

| 1842 | Current structure opens to the public |

| 1882 | Bronze statue of Washington is installed |

| 1965 | Federal Hall Memorial becomes a landmark |

| tidbit | George Washington |

| sight | Trinity Church |

| wiki | Federal Hall |

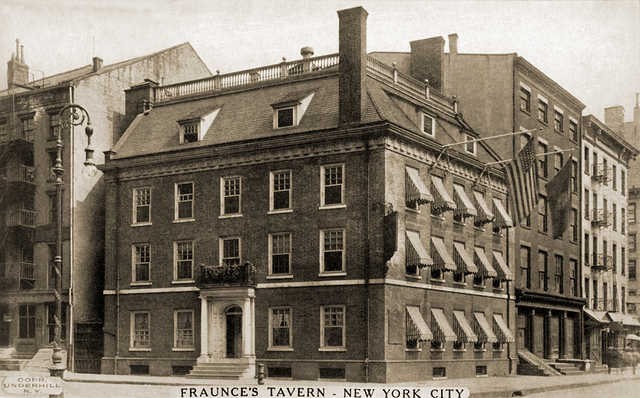

The brick building at 54 Pearl Street was built by Etienne “Stephen” DeLancey, the son-in-law of New York Mayor Stephanus van Cortlandt in 1719. In 1762, van Cortlandt’s heirs sold the building to Samuel Fraunces, a restaurateur who is thought by many to have been an American spy during the Revolutionary War. Fraunces converted the building into a tavern originally named Queen’s Head for Queens Street, which is now known as Pearl Street.

Before the American Revolution in 1775, the tavern was used as a meeting place for the Sons of Liberty, a secret society formed to fight British taxation imposed on the colonies and to protect the rights of colonists. They were also responsible for the Boston Tea Party in 1773, one of the most infamous acts of rebellion in American history. During the War, General George Washington used the tavern as a headquarters.

After the war was won, 54 Pearl Street became the first offices for the Departments of Foreign Affairs, War and Treasury from 1785-1788. The government then promised to move its offices south, and the building once again served as a tavern.

In 1825, the Eerie Canal was opened, which gave way to easy travel into the city and resulted in a population influx. Housing was in high demand, and Fraunces Tavern began operating as a boarding house with a bar until the 1840s, when large and elegant hotels began to replace these humbler forms of accommodation. In order to function as a proper boarding house, two additional stories were added to the original structure, which were then divided into thirteen bedrooms.

Due to the building’s place in American history, the tavern remained an important gathering place for Patriots into the 19th century. Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr attended a dinner hosted in the tavern a week before their famous duel that killed Hamilton, and also served as the site of Washington’s farewell to his troops in 1883.

Fraunces Tavern was threatened with demolition in 1900, but was saved by the Daughters of the American Revolution, an organization made of descendants of those involved in the United States’ independence. In 1904, the Sons of the Revolution, the Daughters’ male counterpart, purchased the property with the funds willed by a descendant of Benjamin Tallmadge, Washington’s chief of intelligence during the Revolution.

The Sons of the Revolution restored the building to its 18th century appearance, removing the extra floors added and all of the modifications made over the decades. The restoration was completed in 1907 and the Fraunces Tavern and Museum was opened on the 124th anniversary of Washington’s farewell to his officers at the Tavern.

The Museum and Restaurant now occupy five buildings on Fraunces Tavern Block.

| 1719 | The mansion is built |

| 1762 | Samuel Fraunces purchases the building and converts it into Queen's Head Tavern |

| 1773 | Boston Tea Party |

| 1775 | American Revolution |

| 1785 | Tavern is converted into the Departments of Foreign Affairs, War and Treasury |

| 1825 | Eerie Canal is opened |

| 1883 | George Washington says farewell to his troops |

| 1900 | Daughters of the Revolution save the tavern from demolition |

| 1904 | Sons of the Revolution purchase the tavern and restore it |

| 1907 | Restored building is completed |

| 1965 | Fraunces Tavern becomes a landmark |

| tidbit | George Washington |

| link | Fraunces Tavern and Museum |

| link | Samuel Fraunces |

| wiki | Fraunces Tavern |

| wiki | Sons of Liberty |

Hanover Square was named after the House of Hanover, the lineage of British monarchs of which King George–the King at the time–was a part in 1714. The Square served as the center of New York’s commodity market for housing the New York Cocoa Exchange and the New York Cotton Exchange, the oldest commodities exchange in the city. It was also known as Printing House Square for its line of newspaper offices.

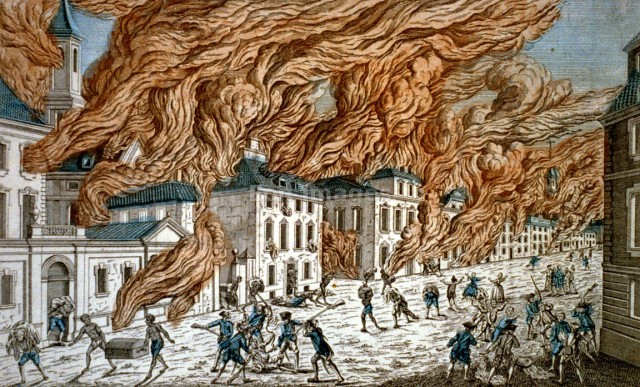

In December of 1835, the Square was also the center of a fire that decimated Lower Manhattan. The Great Fire of 1835 began in a five-storey warehouse on present-day Beaver Street. As the fire spread, it consumed thousands of imported and priceless goods from Europe and Asia stored in the surrounding warehouses. Strong winds carried the fire throughout the area destroying over 600 buildings. When firefighters responded to alarms, they had no way of putting out the fire, as the East River had frozen over due to the -17 degree weather. They were then forced to drill though the ice, but when they finally did reach water, it was so cold that the water froze in the pipes and hoses.

In a desperate attempt to stop the fire, the Marines brought over gunpowder from the Brooklyn Navy Yard and began blowing up buildings in the fire’s path in order to limit its fuel.

This fire led to the construction of the Croton Aqueduct, which would provide a source of water for firefighters in times of emergency, no matter what the weather.

The Great Fire of 1835 remains the largest fire in New York City history.

| tidbit | Croton Distributing Reservoir |

| link | Wiki |

| link | Great Fire of NY 1835 |

| link | New York's Great Fire of 1835 |

Only six days after the British took New York from the Dutch in 1776, a raging fire broke out on the night of September 21, 1776. According to eyewitnesses, the fire started in Fighting Cocks Tavern, which was located at the bottom of what is present-day Whitehall Street. Dry weather and strong winds spread the fire east and west, destroying 10-25% of the city. Though the exact number of damaged buildings is unknown, it is speculated that between 400 and 1,000 of the city’s 4,000 buildings were destroyed. Among those burned was the original Trinity Church building on 109 Greenwich Street, which went up in flames within minutes.

Many believed that the fire was the work of politically-fueled arsonists, but it was unclear whether it was the work of passionate Patriots or radical Loyalists. Each side blamed the other, but it was the Patriots who were ultimately pinned with the crime. British soldiers claimed that their fire-fighting equipment was sabotaged and prevented them from putting out the fire. As a result, over 200 Patriots were arrested and many of the prime suspects were hanged.

Days prior to the event, General George Washington met with the Continental Congress to discuss a defence strategy against the anticipated British occupation. At the meeting, it is said that there was a suggestion that they burn the city to the ground in order to keep it out of British hands. Though Washington rejected this suggestion, it is believed that it may have inspired a group of Patriots to act independently and set fire to the city.

After the incident, the British set up their own fire department in order to prevent any similar events from happening. Despite their efforts, the city remained far behind in fire-fighting strategies for decades. Devastating fires continued to break out in the city throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, with the most notable being the Great New York City Fire of 1845 and the General Slocum Fire of 1904.

| sight | Trinity Church |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Wikipedia |

Bowling Green Park, the first official park in New York, was established and named by a resolution of the Common Council on March 12, 1733. It was leased at an annual rent of one peppercorn to John Chambers, Peter Bayard, and Peter Jay, who were responsible for improving the park with grass, trees, and a wooden fence “for the Beauty and Ornament of the Said Street as well as for the Recreation & Delight of the Inhabitants of this City.”

Following a public reading of the Declaration of Independence in City Hall Park, a patriotic mob surged down Broadway and tore down the gilded lead statue of George III that had stood in Bowling Green since 1770.

via NYC Parks

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | Bowling Green's Fence Posts |

| internal | A Revolutionary War Legend at Bowling Green |

| internal | Bowling Green |

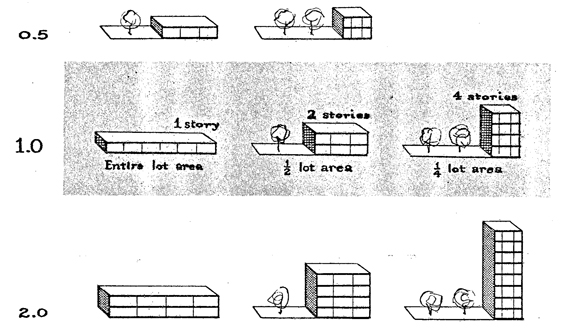

As the New York City skyline grew more crowded, residents began protesting the loss of light and air, a consequence of the new highrise buildings springing up all over Manhattan. Photojournalist Jacob Riis’ 18-page 1890 article in Scribner’s Magazine entitled “How the Other Half Lives” helped to lead the fight for housing reformation after he exposed the adverse living conditions of the Lower East Side tenements. As a result of the widespread unrest over housing, city officials passed the New York State Tenement House Act of 1901, which banned the construction of dark, poorly ventilated tenement buildings in the New York.

Though housing conditions were taken care of in 1901, there were no zoning laws controlling how offices and other buildings were designed and built. In 1916, the city passed The Zoning Resolution of 1916, which set height limits, designated residential districts, and gave rise to both the tall, slender design characteristic of the city’s business districts and the three-six-storey residential buildings found all over the city today.

By 1961, however, the 1916 zoning laws no longer seemed to benefit the city. After lengthy deliberations, the new Zoning Ordinance of 1961 was enacted. The new regulations limited the bulk and height of buildings allowed under the old ordinance by limiting the amount of space that a property owner could build within the footprint of the lot. The new resolution encouraged developers to incorporate plazas–like 55 Water Street’s Elevated Acre–in their designs in an effort to create open space. It also aimed to simplify zoning regulations and offer residents more public amenities. If a developer agreed to include a plaza in their design, they were given extra space in return, adding an extra 6-and-a-half floors to the structure. This barter system resulted in unused or useless plazas and ugly monolithic buildings.

Some criticize the resolution, claiming that these wider buildings overwhelm their surroundings and that the new open spaces created were not always attractive or necessary. Despite these criticisms, the 1961 Zoning Ordinance continues to rule the city’s development plans.

| 1890 | Jacob Riis publishes "How the Other Half Lives" |

| 1901 | New York State enacts the Tenement House Act of 1901 |

| 1916 | Zoning Resolution of 1916 is passed |

| 1961 | Zoning Ordinance of 1961 is passed |

| sight | Seagram Building |

| sight | Elevated Acre |

| internal | gDoc |

| sight | About Zoning |

| sight | Simple Rules for a Complex Society |

The past few centuries have shown a radical transformation within Lower Manhattan. The Financial District, the birthplace of the city which was once dominated by farms, has grown to cater to New York’s status as the corporate capital of the world. Massively modern, glass-coated skyscrapers tower over narrow winding streets, coming quite a long way from their origins as Dutch and Native American rural stomping grounds.

Despite not being the first place that comes to mind when thinking about art, the Financial District is abundant with public art and powerful architecture. We’ll explore over 15 different sites by famed artists such as Mark di Suvero, Keith Haring, and Isamu Noguchi that reinforce the neighborhood’s strong corporate identity while contrasting the swaths of contemporary, colorless skyscrapers that surround them.

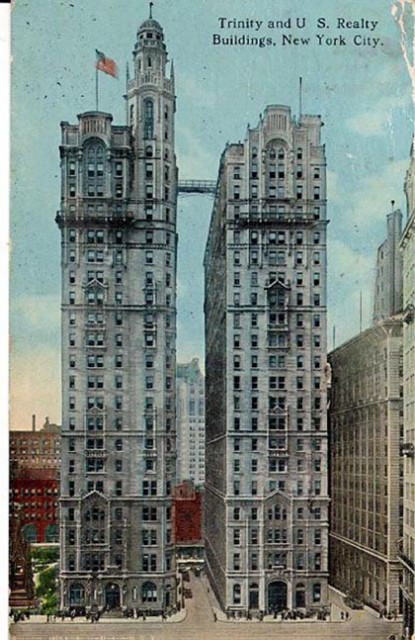

The twin Gothic skyscrapers at 111 and 115 Broadway caused quite a commotion when they were completed in 1905 and 1907. Not only were they among the earliest Gothic-inspired skyscrapers in the city, but a whole street had to be relocated in order to make room for the brand new buildings.

In 1902, US Realty and Construction Company–one of the many large corporations that began replacing individual building developers in the early 20th century–bought the old Trinity Building at 111 Broadway. The long, narrow building, which was designed by Trinity Church architect Richard Upjohn, was wedged between Trinity cemetery on the south and a small Thames Street on the north, with only 40 feet of frontage on Broadway. In a time before efficient indoor lightning, the location offered natural lighting ideal for office buildings.

US Realty’s original plan was to combine the Trinity plot with the land on the opposite side of Thames Street and move the street along the edge of Trinity cemetery. Because of delays that held up the project, though, US Realty went ahead and began erecting their new building on the site of the original Trinity Building itself. In 1904, the street relocation plan was modified, and it was decided that instead of moving Thames Street to the south, it would be shifted 28 feet north of its original location.

Architect Francis H. Kimball, whose architectural firm designed the Empire State Building in the late 19th century, designed the new Trinity Building in the neo-Gothic style, which was not yet an accepted style for skyscrapers. Although the connotations of Gothic architecture such as spirituality and craftsmanship didn’t match those of capitalism and big business, Kimball chose the style because of the building’s proximity to Trinity Church. The neo-Gothic office building and the old Gothic church, Kimball thought, would complement each other perfectly.

By the time Trinity Building opened in 1905, US Realty had bought the plots on the north side of Thames Street, where the corporation began clearing the land and building the US Realty Building at 115 Broadway. Trinity’s sister building, which was also designed by Kimball, would not be completed until 1907.

The media praised the new buildings for their beauty, architectural innovation, and its harmony with the old church. Though the buildings went through several bouts of foreclosures and vacancies in the 1990s, the two skyscrapers continue to adorn the Manhattan skyline and serve as testament to the once unheard of Gothic-style skyscraper.

| 1902 | US Realty and Construction Company purchases old Trinity Building |

| 1904 | Old Trinity Building is demolished; Thames Street is relocated |

| 1905 | New Trinity Building opens |

| 1907 | US Realty Building opens |

| sight | Trinity Church |

| internal | gDoc |

| sight | Twin Gothic Towers That Changed City's Geography |

| sight | Landmarks Preservation Committee: US Realty Building |

On a rainy day on October 28, 1886, New York City was celebrating the unveiling of French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty with a lavish parade. While children had the day off from school and stores and offices were closed, the city’s Wall Street traders were the only ones in the city working. Forced to watch the celebration from their office windows, the businessmen joined in in the parade the only way they could: with reams of confetti-like ticker tape, which were used in stock ticker machines to print financial data. As the parade continued down Wall Street and passed by the New York Stock Exchange, the traders opened their windows and threw firstfuls of shredded white paper onto the streets to celebrate the new statue, giving birth to the ticker-tape parade.

Ticker-tape parades were soon used to celebrate all different kinds of events in the city, from President Teddy Roosevelt’s return from his 1910 African safari to Albert Einstein’s first visit to the United States. Though some rallied for their discontinuation in the early 20th century due to the disturbances they created and for their tiresome overuse, the parades remained the main form of public celebration in the city for decades.

New York saw its most extravagant ticker-tape parade on Victory Over Japan Day on August 14, 1945. To celebrate Japan’s surrender after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, New Yorkers filled the air with confetti, hat trimmings, and feathers. That night, over 3,000 street sweepers were sent out to clean up, only to have their work undone when the celebrations continued the next morning. In all, celebrators flung over 5,000 tons of material onto the city streets.

As the stock exchange switched to electronic boards for their financial information in the 1960s, ticker-tape parades began to dwindle, with only a handful held in the 1970s and 1980s. Though they saw a brief resurgence in the 1990s, the parades were never as popular as they were at their inception. In recent years, ticker-tape parades have been few and far between. Today, machine-shredded waste paper has replaced obsolete ticker-tape reams.

| 1886 | New York hosts the first ever ticker-tape parade |

| 1921 | Parade is thrown in honor of Albert Einstein's first visit to the US |

| 1945 | Extravagant V-J Day ticker-tape parade thrown |

| internal | gDoc |

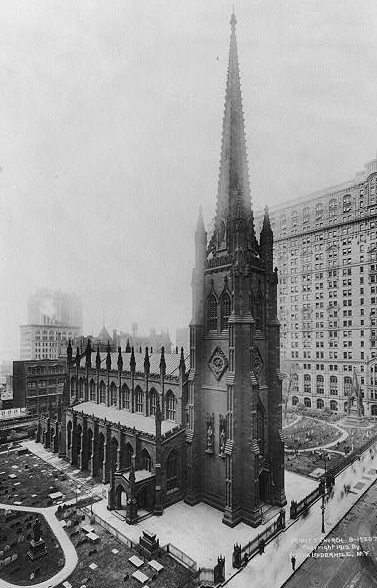

For over three centuries, 109 Greenwich Street has been the site of three different buildings–all with the same name. The first Trinity Church, which was built in 1751, stood on Greenwich Street for only 25 years before it was destroyed in the Great Fire of New York. It was then rebuilt in 1790, and then rebuilt again in 1846 after it was demolished due to snow damage.

The following year, the church commissioned architect Richard Upjohn to design a Gothic stone structure to serve as the parish’s new place of worship. The church’s spire and cross were the highest point (not building) in New York until 1890 when the New York World Building was built.

The Churchyard is the only site at 109 Greenwich Street that has remained unchanged since the 17th century. The oldest headstone in the graveyard is that of five-year-old Richard Churcher who died in 1681, most likely of smallpox. Not only is his headstone the oldest in the churchyard, but it is the oldest headstone in all of New York City. Notice it has engraved details not only on the front but also on its back!

The cemetery is also the resting place of various historical figures such as Alexander Hamilton, a number of Revolutionary War heroes, and some lesser-known signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Also located in the churchyard is the grave of John Peter Zenger, a printer whose 1733 libel court case was responsible for the establishment of freedom of the press. When Zenger began printing articles in The New York Weekly Journal about the political corruption of New York’s then colonial governor, William Cosby, he was thrown in jail for opposing the government. Zenger didn’t deny that he printed the pieces, and neither did his lawyer, Andrew Hamilton. Hamilton asked the jury to prove the publication’s criticisms false saying, “It is not the cause of one poor printer, but the cause of liberty.” The jury returned after only a few minutes of deliberation with the verdict of not guilty. Though Freedom of the Press was not a written liberty until the passage of the First Amendment in 1791, newspapers and other publications felt that they were freer to express their political opinions after Zenger’s trial. This newfound freedom gave way to the publication of political pamphlets that played an important role in the American Revolution.

Trinity Tree Root, the red metal sculpture that now stands outside of the church, was installed in 2005 to commemorate September 11, 2001. When the Twin Towers were hit, a large sycamore tree shielded St. Paul’s Chapel, Trinity’s sister church, from damage. The tree was eventually cut down due to damage from the attack, but its roots and stump remained in front of the church. Artist Steve Tobin was commissioned to excavate the roots and create the sculpture that would stand in front of Trinity. The sculpture is a bronze cast of the roots of the sycamore.

Today, Trinity Church is still an active church. It is also a prominent real estate owner and investor, with its SoHo, Greenwich Village, and TriBeCa properties being among the most valuable in the city.

| 1697 | First Trinity Church built |

| 1776 | Trinity Church destroyed in Great Fire |

| 1790 | Second Trinity Church constructed |

| 1839 | Trinity Church demolished |

| 1846 | Current Trinity Church consecrated |

| 1976 | Trinity Church landmarked |

| 2005 | Trinity Tree Root is installed |

| internal | gDoc |

The raised plaza hidden away at 55 Water Street has existed since the building’s completion in 1972, but it remained closed off for decades until 2005. The office building at 55 Water Street was built under the Zoning Resolution of 1961, which encouraged the incorporation of plazas in order to create more space around the city open to the public. Under the new laws, a building that included a plaza was allowed to build 6-and-a-half extra floors. Though it was supposed to serve as a public space for neighborhood residents, the plaza at 55 Water Street was shut down soon after the building opened and was closed off entirely to the public, violating the terms of the Zoning Resolution. The space then became a hotspot for drug deals and other illegal activity.

What was originally built as a trade-off for a few extra storeys soon became the center of a debate between financial district residents and Goldman Sachs. In 2001, the Goldman Sachs Group controversially proposed to remove the plaza entirely and erect a 240-foot-high building in its place. In exchange for the new building space, the Group promised to build bike paths, walkways, and install seating around the neighborhood and to contribute to the renovation of Vietnam Veterans Plaza on the other side of the building. Despite these proposed improvements, the Community Board and residents rallied against the Group in order to preserve the plaza.

The community eventually won the battle, and in 2005, Rogers Marvel Architects redesigned the space, adding seating and gardens to the previously bare and bleak plaza. Today, the Elevated Acre is open to the public and serves as a site for weddings, concerts, and other events and fulfills the 1961 Zoning Resolution requirements.

| 1961 | Zoning Resolution of 1961 is passed |

| 1972 | 55 Water Street is completed |

| 2001 | Goldman Sachs Group proposes to build a new building in place of the plaza |

| 2005 | Rogers Marvel Architects redesigns the space and opens it to the public |

| tidbit | 1961 Zoning Ordinance |

| internal | gDoc |

| sight | Commercial Real Estate; A Plaza Few Use But Everyone Wants |

| wiki | 55 Water Street |

This steel sculpture by Taiwanese artist Yuyu Yang serves as a mirror of the surrounding environment and aims to harmonize man and his environment. Yang refers to his work as “lifescapes” rather than as sculptures due to their spiritual effect on viewers.

The shiny, 12-foot-high, 4,000-pound disk stands upright and seems to fit perfectly into the cutout of the square, matte slab next to it. Looking through the cutout and into the reflection of the disk, the viewer is given the illusion of deep space and of internal tension in the juxtaposition of the shapes and textures of each free-standing piece.

Yuyu Yang was a prominent artist in China and Taiwan. Yang worked in a myriad of media including paper, bronze, wood, cloth, clay, and stainless steel. In the 1990s, the artist turned almost exclusively to stainless steel, a material which he felt allowed him to fluidly express the spiritual themes and values reflected in Chinese philosophy such as the oneness of the individual and his or her surroundings.

| 1973 | East West Gate installed |

| link | East West Gate: Yuyu Yang's Lifescape Sculpture |

| internal | gDoc |

Though Keith Haring is better known for his paintings, but he started making sculptures in 1985. In 1989 he made “Untitled (Two Dancing Figures)” from aluminum, which was then painted. The figures in the sculpture seem like they danced out of Haring’s canvas; they are similar in style to his drawings and street art. Dancing figures were common throughout Haring’s work, including the figures he painted on the Bowery Mural. Haring liked sculpture, since he felt it was a more permanent medium than painting. “Untitled (Two Dancing Figures)” was part of the Lever House Art Collection from 2005-2006, it is now installed at the corner of Pearl and State Streets.

| 1989 | Untited (Two Dancing Figures) installed |

| link | Collections: Keith Haring |

| internal | gDoc |

Mark di Suvero’s “Joie de Vivre,” a 70-foot tall sculpture in Zuccotti Park, became a gathering place for members of the Occupy Wall Street movement. This sculpture, made of steel beams painted red, has similarities in color, size, and materials to di Suvero’s other work. Agnes Gund, president of MoMA, donated the sculpture to the city. “Joie de Vivre” was previously installed near the New York side of the Holland Tunnel; before that, it was at Storm King sculpture park in upstate New York, and on exhibit in Paris. Some Occupy protesters mistakenly thought it was commissioned by downtown investment firms as a symbol of their wealth. Ironically, the sculpture intended for the people of New York was barricaded after an Occupy protester climbed up the sculpture. Di Suvero, who said he holds some communist views, protested the Vietnam and Iraq wars, and was arrested several times.

| 1998 | Joie de Vivre installed |

| link | Mark Di Suvero, Joie de Vivre, 1998 |

| internal | Mark di Suvero - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

A sliver of a road across from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Coenties Slip has a rich marine and artistic history. Named after a Dutch family, the Coenties Slip was built before 1766 as a man-made place to dock boats. At that time, the East River came up to what is now Water Street. The Slip was filled in in 1835, and became a street with the same name. Coenties Slip was the location of many book publishers. In fact, Herman Melville mentions Coentie Slip in Moby Dick, published in 1851. In the 1950s, the Slip was home to pop and minimalist artists who formed the Coenties Slip Group, including Agnes Martin, Robert Indiana, and Ellsworth Kelly. Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns were involved in the group, although they did not live on Coenties Slip. Since 2006, Bryan Hunt’s sculpture “Coenties Ship” has commemorated the history of the Slip.

| 2006 | Coenties Ship installed |

| internal | Coenties Slip - Wiki |

| link | Bryan Hunt |

| internal | gDoc |

| link | The Guardian on Agnes Martin |

Isamu Noguchi’s “Sunken Garden” brings the calming atmosphere of a Japanese Zen garden to downtown New York. The garden, installed below the Chase Manhattan Plaza, contains basalt rocks from the Uji River in Japan, and granite tiles from Vermont. The garden becomes a fountain in the summer. When it was first built, people added goldfish to the pond. Noguchi, a New York-based sculptor, often collaborated with architects, including Gordon Bunshaft, the architect of 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza. This plaza has been compared to Noguchi’s Beinecke Library courtyard at Yale because both spaces are visible from above and around the garden at the underground levels of the buildings.

| 1964 | Noguchi completes Sunken Garden |

| link | New York Public Art Curriculum: Sunken Garden |

| wiki | Isamu Noguchi |

| link | Isamu Noguchi's Utopian Landscapes |

| internal | gDoc |

Isamu Noguchi’s “Red Cube” is not really a cube at all. The 28-foot sculpture is a three-dimensional parallelogram; it is tilted and longer than it is wide. The sculpture’s bright color creates a point of interest for the pedestrian, and the center hole acts as a viewfinder to the office building’s upper floors. Noguchi, a Japanese-born American artist, studied painting and sculpture in New York and Paris. He was involved with the artists community in Greenwich Village, his studio was in MacDougal Alley. Noguchi worked with architects and other artists throughout his life, including dancer and choreographer, Martha Graham.

| 1968 | Noguchi installs Red Cube |

| wiki | Isamu Noguchi |

| link | New York Public Art Curriculum: Red Cube |

| link | Art Nerd New York: Red Cube |

| internal | gDoc |

Louise Nevelson Plaza opened in 1978, dedicated to and featuring work by the sculptor. For her plaza, Nevelson designed seven sculptures, ranging from twenty to seventy feet in height. Nevelson was inspired by flags, and wanted her sculptures to seem like they were flying, so she raised them on poles. The group of sculptures is aptly entitled “Shadows and Flags.” Nevelson often works with wood, plexiglass, and found objects to create her sculptures, but for “Shadows and Flags” she used a more outdoor-appropriate Cor-Ten steel painted black. After 9/11, the plaza was rearranged to allow better surveillance at the Federal Reserve, adjacent to the plaza. The sculptures were removed for restoration in 2008 after the surfaces were damaged in 9/11.

| 1978 | Louise Nevelson Plaza officially opens |

| 2004 | Plaza transformed into tree-filled open space |

| 2010 | Plaza re-opened to the public |

| wiki | Louise Nevelson |

| link | Downtown Alliance: Louise Nevelson Plaza |

| link | Louise Nevelson Foundation |

| internal | gDoc |

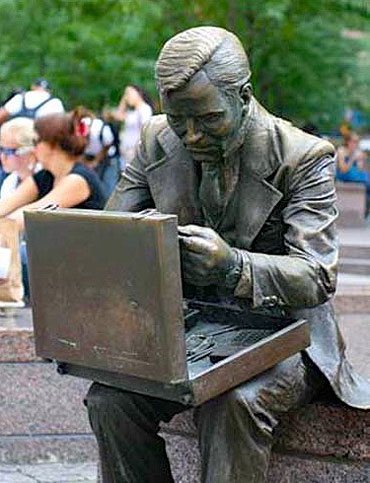

John Seward Johnson II’s sculptures capture the events of everyday life; in this case, an office worker looking inside his briefcase. The sculpture was commissioned by Merrill Lynch in 1982 and placed in Liberty Park, now Zuccotti Park. On September 11, 2001, the sculpture came to represent much more than an office worker. The sculpture was damaged in the events and covered in debris, but became an unofficial memorial to the victims, many of whom worked in the financial district. People left items at the sculpture in memorial, and Johnson incorporated these items in a copy of the “Double Check” sculpture entitled “Makeshift Memorial.” “Double Check” remains at Zuccotti Park and “Makeshift Memorial” can be seen at the Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, NJ. However, the statue’s symbolism was forgotten by the Occupy Wall Street protesters, who saw the sculpture as a sign of corporations and capitalism.

| 1982 | Sculpture installed by Johnson |

| 2001 | 9/11 attacks significantly damage sculpture |

| 2006 | Liberty Plaza Park renamed Zuccotti Park |

| 2011 | Occupy Wall Street occurs in Zuccotti Park |

| link | Daytonian in Manhattan: Double Check |

| link | John Seward Johnson II Official Website |

| internal | John Seward Johnson II - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

On December 15, 1989, the Dow Jones closed at 2739.55, 51 points behind its 1989 high. But Arturo Di Modica, a Soho-based sculptor, was feeling bullish. The previous evening he had visited Broad Street in Lower Manhattan, carefully timing the police patrols around the New York Stock Exchange. He determined that he would have a 4 ½ minute window to deliver the largest Christmas gift the City of New York ever received: a three-and-a-half-ton, 18-foot-long, bronze “Charging Bull.” Di Modica created this piece of guerilla art at his Crosby Street studio, ultimately spending more than two years and $350,000 to create, transport and place it under the Christmas tree in front of the exchange.

Di Modica was inspired by New York’s fighting spirit in the wake of the 1987 stock market crash. From the start, “Charging Bull” seemed possessed of the same spirit. Although “it was love right away” with New Yorkers, as Di Modica observed that night, the following morning the stock exchange, itself, was less enamoured. In fact, all it wanted to do was return the gift. It unsuccessfully sought to make the police do it, and then secured a private contractor to cart it to a Queens impound lot. According to the New York Times, by day’s end, the Dow Jones was off another 14.08 points. Wall Street analysts were blaming “obscure economic forces,” but New Yorkers, upset about the departure of the bull, recognized a real leading economic indicator when they saw one. Parks Commissioner Henry Stern, Mayor Ed Koch and activist Arturo Piccolo of the Bowling Green Association found a home for “Charging Bull” at Bowling Green within a few days.

Officially, its status is still under siege. The bull is on loan to the city from Di Modica, a circumstance that normally limits its display to only one year. It has only a temporary permit to stand at the Bowling Green location, which the City indicated would not be permanent. DiModica has offered it for sale to anyone willing keep it in its current location, but so far, no takers.

Non officially, it is more than capable of defending its territory. In the years since it arrived, it has fought off copyright infringement by Walmart, by North Fork Bank, by ten other institutions who have used it in advertising, by Random House and by the Occupy Wall Street movement. It survived the biggest Christmas sweater of all time, a full-body, form fitting blue and purple crocheted creation, designed by another guerilla artist, Oleck, mercifully torn off by a caretaker of the park.

It has weathered disasters, both natural and man-made. Nonetheless, it holds its own, day in and day out, tolerating both tourists and traders who feel bullish, literally: apparently it’s good luck to rub the bull’s testicles.

— Carol Cofone

| 1989 | Di Modica "installs" Charging Bull |

| link | Charging Bull Official Website |

| wiki | Charging Bull - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

Jean Dubuffet’s “Group of Four Trees” in front of 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza don’t really look like trees: they don’t have leaves or roots, and are made of concrete. This abstract sculpture, 40 feet tall, consists of organic forms arranged to remind the pedestrian of a forest. Commissioned by David Rockefeller in 1972, the Trees breaks from the rigidity of rectilinear skyscrapers which surround the plaza. Dubuffet’s abstract work, known as “l’art brut (art in raw),” uses organic shapes formed by lines. His sculptures are three-dimensional representations of his paintings and drawings. Dubuffet worked in France until his death, but lived in Greenwich Village for several years, where he used trash and found objects to create sculptures.

| 1969 | David Rockefeller asks Dubuffet to form a sculpture for the plaza |

| 1972 | Dubuffet finishes sculpture |

| link | New York Public Art Curriculum - Group of Four Trees |

| internal | gDoc |