Who the #$&% Is Jackson Pollock? is a documentary following a woman named Teri Horton, a 73-year-old former long-haul truck driver from California, who purchased a painting from a thrift shop for $5, only later to find out that it may be a Jackson Pollock painting; she had no clue at the time who Jackson Pollock was, hence the name of the film.

| sight | Jackson Pollock's Apartment |

| sight | Jackson Pollock's Penthouse |

| wiki | Wikipedia |

| article | NYTimes: Could Be a Pollock; Must Be a Yarn |

The Village Gate nightclub closed in 1993, but its sign still remains on the corner of Thompson and Bleecker Streets. When Art D’Lugoff opened the club in 1958, it served as a performance space for artists like Nina Simone, Miles Davis, and Billie Holiday. It was also where Aretha Franklin made her first New York appearance.

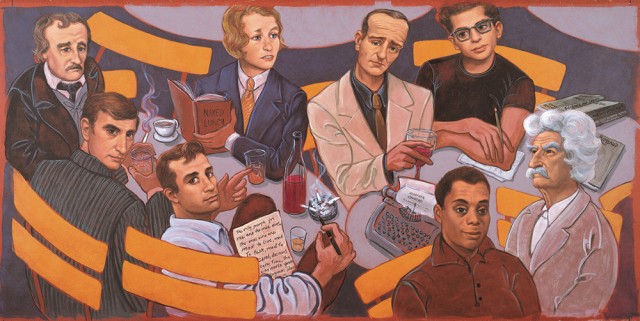

Bohemorama is a mural by illustrator Vicki Khuzami. The acrylic canvas work in LaGuardia Place is an homage to the famous bohemian artists, writers, and musicians who called the Greenwich Village home. The piece includes images of Edgar Allan Poe, Bob Dylan, Andy Warhol, Miles Davis, Allen Ginsberg, and Mark Twain, among others.

Khuzami began her career restoring 19th century paintings, and after a few years began illustrating book covers. In 1993, she and a group of artists designed new murals for Washington DC’s Capitol Building. She has designed murals for the Brooklyn Botanical Garden, the US House of Representatives, Disneyland Tokyo, and Bloomingdale’s.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | CultureNow article |

| internal | Artist bio |

| internal | Artist website |

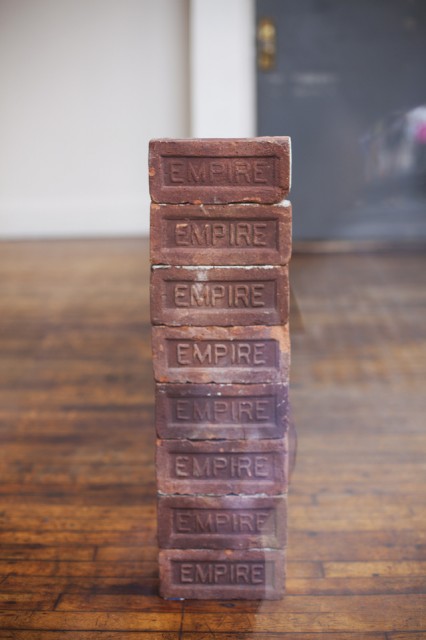

Manifest Destiny is a stack of bricks imprinted with the words “Empire” by Minimalist artist Carl Andre. About his work, which is incredibly meticulous, precise and stark Andre has said there no ideas hidden hidden, they simply are what you see. This mystery and beauty gives his work its magical draw.

| sight | Donald Judd's Studio |

| sight | The Guardian – Carl Andre: 'I'm a hopeless drawer – and a terrible painter' |

| sight | FT – Minimalist in Manhattan |

| sight |

| internal | gDoc |

S.J. Kessler and Sons, landscaping and gardens by Sasaki, Walker, and Associates

1975 was not only a revolutionary time in the culinary world because of Food in SoHo, but also for the invention of the iconic treat, Pop Rocks. Anyone who lived through the 1970s and 1980s remembers the carbonated candy that fizzes in the mouth. The novel idea was patented by General Foods in 1957, although it wasn’t made available publicly until 1975. The candy saw some tough times when rumors abounded about the fatal dangers of mixing Pop Rocks with Coca Cola, and parents had to be assured that their children’s stomachs would not explode. It was pulled from the shelves in the 1980s due to declining popularity but eventually had a resurgence and continues to be sold today.

| internal | How Pop Rocks Work |

| article | The Death of Little Mikey by Pop Rocks and Soda |

| internal | Pop Rocks - Wiki |

The Vertical Earth Kilometer is one of a series of four pieces created in the 1970s by artist Walter De Maria. A one-kilometer brass rod was fitted into the ground in Kassel, Germany, with only one end of the two-inch diameter rod flush to the surface and visible. The work asks for viewers’ trust by telling us that the piece extends one full kilometer into the earth, and—along with its sister piece here in Soho, Broken Kilometer—encourages us to question what we think we know about distance.

| 1977 | Walter De Maria installs Vertical Kilometer in Kassel, Germany |

| link | Atlas Obscura - Vertical Kilometer |

| internal | Walter De Maria - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

Walter De Maria was an American artist known for his minimal and conceptual art and his use of landscape in his works. Originally from California, De Maria moved to New York in his mid-twenties 1960, where he started using geometric shapes and manufactured materials in his works, many of which are huge installations filling rooms and fields. His most well known series consists of The Lightning Field, The Vertical Kilometer, The Broken Kilometer, and The Earth Room. The Lightning Field is a one mile by one kilometer grid of metal posts in New Mexico that brings manmade materials outdoors, while The Earth Room is an apartment full of dirt here in Soho that blurs the lines between inside and outside.

De Maria lived and worked in his home, an abandoned Con-Ed substation-turned-studio on 421 East 6th Street in the East Village from 1980 until his death in 2013.

| 1960 | Walter De Maria moves to New York |

| 2013 | Walter De Maria dies |

| article | NY Times: Walter De Maria Dies at 77 |

| internal | Walter De Maria - Wiki |

| internal | Earth Room Munich. German Article / Image Contact? |

| internal | gDoc |

Tony Goldman was a real estate developer whose buildings and love of the arts helped shaped the Soho we know today. Goldman eschewed the term “developer” in favor of describing himself as a long-term investor. He believed not just in building, but in revitalizing neighborhoods. In the mid-to-late-1970s, at a time when Soho was a run-down place that most developers overlooked, Goldman saw the potential of its large, open, industrial spaces that were transformed by artists into livable lofts.

Goldman Properties is responsible for many buildings in New York, including 25 Bond Street and the commissioned Ken Hiratsuka work in front it. They also commissioned the Francoise Schein piece, Subway Map Floating on a NY Sidewalk, in front of their offices at 110 Greene Street.

He passed away in 2012 at the age of 68, and today his daughter runs Goldman Properties. Between New York and Miami, where most of their projects are, they continue to promote the ideas of urban revitalization and public art.

| link | The SoHo Building |

| article | NY Times: Tony Goldman Obituary |

| article | Tony Goldman is SoHo Cool |

| internal | Tony Goldman - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

Soho is one of New York’s most famous neighborhoods, taking its name from its position SOuth of HOuston Street (pronounced “How-ston”) and north of Canal Street. Today it is known as a shopping district, but the area has a rich history that led to the abundance of art we’ll see on this tour.

Soho’s modern history started in the 1600s, when the land was given to freed slaves and remained farmland for more than a century. During this time, the main water source for the city was the Collect Pond, which, by the early 1800s, had become polluted and unusable. The pond was drained via a canal, which later was filled and became the namesake street.

By the mid-1800s, the area’s population was growing. Cast iron buildings started sprouting up. Lord & Taylor and Tiffany & Company had stores on Broadway, and the neighborhood became a center of shopping, entertainment, and theater. However, as brothels started to move in, residents moved uptown. The invention of cast iron construction allowed for taller, stronger buildings with larger windows and open floor plans, which was the perfect setting for industry to bloom. Soon the textile industry had taken over what had been a bustling social neighborhood.

That era lasted until the mid-1950s when textiles moved to the South and oversees. By the mid-1900s, the area was industrial wasteland during the day with empty, desolate streets at night. Its nickname was “Hell’s Hundred Acres.” Things started to change in the 1960s when artists discovered the huge, empty industrial lofts that could serve as both homes and studios. While the living conditions were frequently less than ideal, the rents were low, and soon the artistic community was thriving. In 1973, the area was declared the SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District. This recognition limited construction on empty lots until 2005, when the restriction was lifted and the neighborhood once again became known for its well located, high-end residences.

The art and architecture of Soho tell the story of this exciting and changing neighborhood—if you know where to look. So let’s get started with our first stop!

| 1775 | Dutch extend Broadway north of Canal Street |

| tidbit | Manatus Map |

| internal | SoHo Slideshow PDF |

| internal | SoHo Timeline PDF |

| article | Living Lofts: The Evolution of the Cast Iron District |

| link | Illegal Living: 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo |

| internal | SoHo Memory: A History of SoHo from the 1700′s through the Present |

| internal | SoHo, Manhattan Wikipedia |

| internal | A Guide to SoHo's Legendary Artists' Lofts |

| internal | NYTimes: 80 Wooster Street |

| internal | gDoc |

Robert Moses was an influential and contentious urban planner. He helped secure the construction of the UN offices in New York City, the Silver Towers were part of his urban renewal program, and he was crucial to building bridges and other important—if often controversial—infrastructure projects throughout the city. However, his legacy is more about his desires to build expressways over public transportation and make the city more car-friendly than people-friendly. His most famous project was the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have carved a 10-lane highway through Soho, Little Italy, and Greenwich Village, all but destroying most of the cast iron buildings which are now landmarked. Jane Jacobs was an advocate who opposed many of Moses’ ideas. Thanks to her grassroots organization the expressway was doomed, and the decline of Moses’ career had started. With fiscally irresponsible decisions made about the World’s Fair, and a campaign against the free Shakespeare in the Park series, confidence in Moses’ competence was on the decline. He died in 1981, at the age of 92, and his legacy—the good and the bad—shape the city today.

| 1941 | Lower Manhattan Expressway idea conceived by Moses |

| 1962 | Lower Manhattan Expressway plan cancelled due to widespread community opposition |

| article | Robert Moses, Master Builder, Is Dead At 92 |

| link | Robert Moses: Documentary |

| link | Unbuilt Robert Moses Highway Maps |

| internal | Lower Manhattan Expressway - Wiki |

| internal | Robert Moses - Wiki |

| internal | The Master Builder |

| internal | Episode 94: Unbuilt |

| internal | gDoc |

The Moon Museum was the brainchild of Frosty Myers, whom we know from The Wall. It is a tiny ceramic wafer, three-quarters of an inch by half an inch, that contains drawings by six artists, including Andy Warhol and Frosty himself. Frosty wanted to create the first museum in space by securing this small—but art-filled—piece somewhere in the 1969 Apollo 12 mission. NASA wasn’t responsive to Frosty’s proposal, but he was able to find an engineer who supported the idea and smuggled the wafer onto the lander module and would therefore be left on the moon. Two days before takeoff, Frosty received a telex (which was like a text message back in 1969) with the message “All systems go,” which was code for success. It remains the first and only museum in space.

| 1969 | Frosty Myers creates Moon Museum |

| 1969 | Smuggled on the moon, making it first art piece in space |

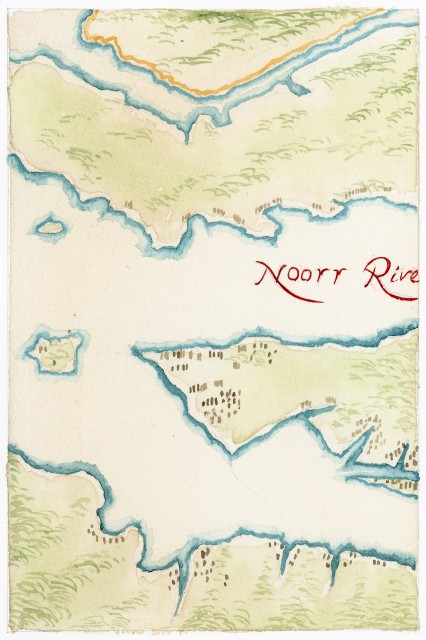

Created in 1639, the Manatus Map is the earliest known drawing of New York City. The full name, “Manatus Gelegen op de Noot Rivier,” or “Manatus located on the North River,” refers to the Dutch name for what is known today as the Hudson River. The map shows many individual farms and plantations, as well as both Conyne and Staten Eylandts. Exactly who drew it is still a mystery, but historians think it was likely the cartographer for the Prince of Nassau for the West India Company of Holland, Johannes Vingboons, or cartographer Joan Vinckeboons. Currently the map is housed at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

| 1639 | Johannes Vingboons draws Manatus Map |

| link | Library of Congress: Manatus Map |

| article | Interpreting the Little-Known Minuit Maps of c. 1630 |

| internal | Johannes Vingboons - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

Jane Jacobs was an American-Canadian journalist whose theories on urban studies and activism helped shape the New York we know today. Born in Pennsylvania in 1916, Jacobs moved to New York in the 1930s and fell in love with Greenwich Village. When Robert Moses tried to build his Lower Manhattan Expressway through the Village and Soho in the 1960s, Jacobs was one of the most vocal opponents, organizing grassroots efforts to oppose the eventually dismantled project. Jacobs passed away in 2006, but her legacy through both her written works, such as “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” and her ideas continue to shape urban planning.

| 1961 | Jacobs publishes the Death and Life of Great American Cities |

| 1968 | Jacobs moves to Toronto |

| 2009 | More Jane Jacobs, Less Mark Jacobs campaign founded |

| article | More Jane Jacobs, Less Jane Jacobs? |

| link | Vanishing New York: More Jane, Less Marc |

| internal | The Death and Life of Great American Cities - Wiki |

| internal | Jane Jacobs - Wiki |

| internal | Urban Designer Series: Jane Jacobs, the Mother of Urban Design |

| internal | How Jane Jacobs Saved SoHo |

| internal | gDoc |

Gordon Matta-Clark was an artist whose media ranged from buildings to photographs to food. He was well known in the 1970s for co-founding Food with Carol Gooden, a restaurant in Soho, which at the time was a shabby, run-down factory area. The restaurant became an enclave for artists, and Matta-Clark frequently cooked dishes that blurred the line between art and dining. His artistic pieces also mixed food and traditional art, such as frying Polaroids in oil with gold leaf. Matta-Clark’s efforts helped establish the Soho art community, and his work often used the abandoned buildings of his surroundings. He would find buildings that were scheduled to be destroyed and then carve out pieces of them, which he called “anarchitecture.” In one instance, he carved away pieces of a neglected pier for two months without notice. When the city found out, they sued him, but the lawsuit was dropped. Matta-Clark died of cancer at the young age of 35.

| 1968 | Matta-Clark graduates from Cornell University's architecture school |

| 1971 | Matta-Clark founds Food with Carol Gooden |

| 1973 | Matta-Clark stops managing Food |

| article | Ned Smyth: Gordon Matta-Clark |

| link | "An ark kit puncture..." |

| link | Guggenheim: Gordon Matta-Clark |

| internal | Gordon Matta-Clark - Wiki |

| internal | Why Food (the Restaurant) Is the Talk of the 2013 Frieze Art Fair |

| internal | Under the Brooklyn Bridge: The Origins of the Restaurant FOOD |

| internal | Deconstructing Reality: Gordon Matta-Clark |

| internal | gDoc |

In 1857, Eder V. Haughwout’s Fashionable Emporium was built at the corner of Broadway and Broome Streets. Haughwout (pronounced “HOW-out”) was a successful merchant who sold china, chandeliers, silverware, and other commodities to those who could afford such goods. He had famous clients, including the Czar of Russia and Mary Todd Lincoln, who bought the White House china here. Gifts from Haughwout’s were presented to heads of state, such as the Emperor of Japan and the King of Siam.

The Haughwout building was almost lost in the 1960s when Chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, Robert Moses, wanted to raze it as part of the plan for the notorious Lower Manhattan Expressway. This is hard to imagine today as the building has two key features that give it an important role as a predecessor to today’s skyscrapers.

The first is that it housed the first functional passenger elevator, which was installed by Elisha Otis in 1857. Peter Cooper actually beat Haughwout to the installing the first elevator shaft four years earlier at the Cooper Union, but Haughwout’s was the first to have the actual elevator. It was powered by a steam-engine in the basement and moved at 0.67 feet per second, quite a bit slower than the 8 feet per second most elevators today travel. The building was hardly tall enough to justify an elevator, but Haughwout felt it would be an attraction to bring people into the shop. That’s 18th century marketing.

The second interesting architectural feature is the use of cast iron. While the material was common in buildings around that time, most buildings had only one street-facing facade. Since Haughwout built his on a corner, there was concern that the structure would not be strong enough to hold the weight of two cast iron facades. In order to solve this, the architects didn’t hang the facades off the brickwork in the standard way. Instead, they used a structural metal frame to support the building, which was a precursor to the steel-framed skyscrapers we see today.

What was once E.V. Haughwout’s Fashionable Emporium is now a lofty office building with shops at street level. It’s history is unnoticeable—there’s no mark of Mrs. Lincoln or the groundbreaking cast iron frame. The elevator has been updated, and you wonder if the people who ride it each day know about its significance.

| 1857 | Haughwout Building Completed |

| 1861 | Mary Todd Lincoln purchases china from Haughwout's Emporium for the White House |

| 1965 | Designed a NYC Landmark |

| 1973 | Added to National Register of Historic Places |

| link | History of the Modern Elevator |

| internal | Robert Moses - Wiki |

| internal | Jane Jacobs - Wiki |

| internal | Haughwout Building - Wiki |

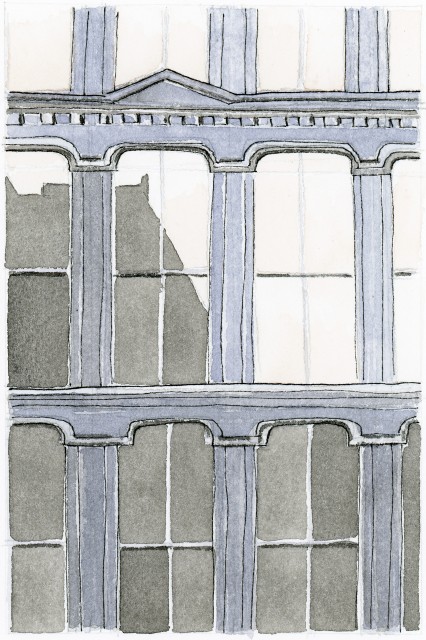

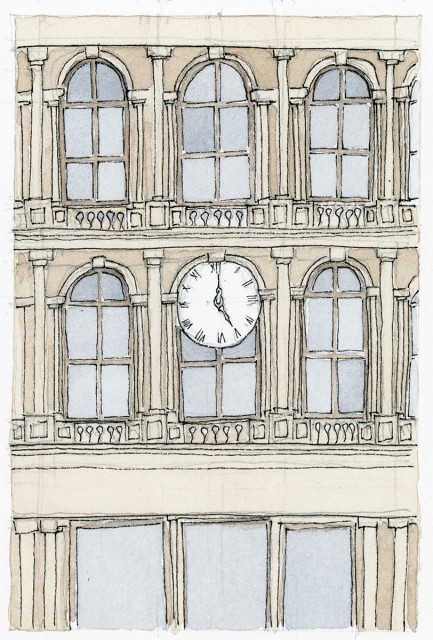

You might do a double take as you get to the corner of Prince and Greene Streets when you see Richard Haas’ mural. 112 Prince has a traditional cast iron facade on the front and a replica of the facade along the side of the building. Known for his trompe l’oeil—French for “deceives the eye”—Haas painted this mural in 1975, blending the two real windows into the design and adding details like shadows, air conditioners, and even a sleeping cat.

Haas had wanted to follow in the footsteps of his idol, Frank Lloyd Wright, to become an architect, but decided in college to study art instead. When he moved from the midwest to New York in 1968, he rented a loft on the Bowery and started drawing buildings and supported himself by commuting weekly to Vermont for a teaching job. In the 1970s, nonprofit City Walls was commissioning murals by abstract artists, and Haas submitted his idea for a realistic image. He chose this wall, originally constructed in 1889, which had boasted painted advertisements in the past.

Haas’ works have been commissioned all over the United States. There are many here in New York City, including the power substation at the Seaport, which is painted to show a cutaway of the Brooklyn Bridge. In Chicago, he painted a residential building that has occasionally fooled people with its realism when they request an apartment with a bay window, only to discover the windows are a trick of the eye.

Some of Haas’ pieces have deteriorated or been destroyed by weather, vandalism, or buildings being razed. And unfortunately the demand for wall murals has practically vanished. Advertisements have reconquered the city, bigger and brighter and more lucrative. Trickery is still at play but of a different kind. There is something wonderful, however, about fooling the eye, pointing out the less obvious and making us consider our perceptual limitations.

| 1975 | Richard Haas completes cast iron mural |

| link | Richard Haas' Official Website |

| article | No Trompe-l’Oeil: A Muralist Loses His View |

| link | Murals That Trick The Eye |

| internal | Trompe-l'oeil - Wiki |

| internal | Richard Haas - Wiki |

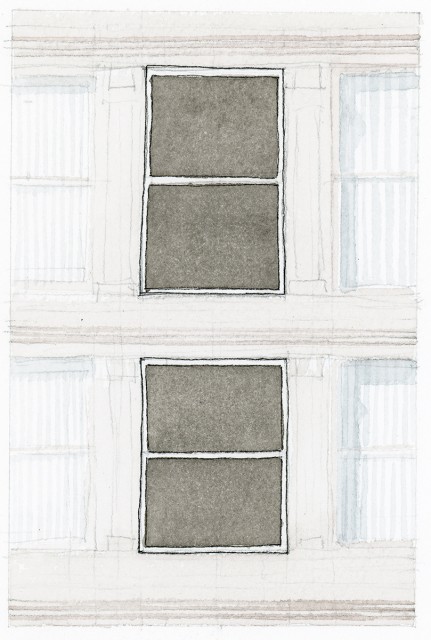

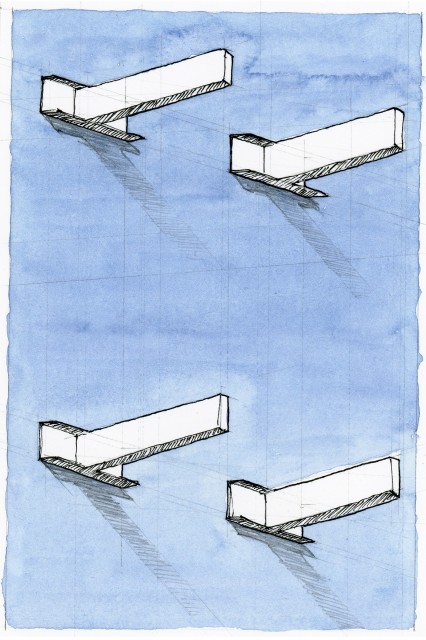

Donald Judd, an artist known for his large, permanent installations, bought 101 Spring Street to serve as his home and studio in 1968. He was a proponent of the idea of permanent installations and disliked that most museums and galleries rotated exhibits. To Judd, a piece of art could change as the environment, light, or political climate fluctuated. He wanted viewers to experience his art over an extended period of time to gain a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the pieces.

With such a contemplative doctrine, it may not come as a surprise that Judd studied both philosophy and art history while at Columbia University. He supported himself writing criticisms for art magazines before becoming one of the first artists to be supported by the Dia Foundation.

Judd bought this entire building for just $68,000 (the equivalent of $464,000 today) and lived here with his family, raising two children and renovating the interior over the years. When he died in 1994, the building became the headquarters of the Judd Foundation. It is set up as a museum in Judd’s taste: showing around 200 pieces of art and 1,800 household objects on permanent display. Very little has changed, and, in fact, It is the only cast iron building in Soho that remains both intact and single-use. It is open to the public through tours that can be booked via the Judd Foundation website.

| 1968 | Judd moves into 101 Spring |

| 2008 | Restoration of 101 Spring begins |

| 2013 | 101 Spring Street reopened |

| article | The Guggenheim: About the Artist |

| link | Judd Foundation |

| internal | Donald Judd |

| internal | The Restoration |

| internal | gDoc |

Point this out at the corner of Prince and Wooster. Corner of 101 Spring Street visible from there.

4th Floor (Parlor): Painting by Frank Stella was exchanged with Philipp Johnson for Sculpture at Glass House

Dia Foundation

The Soho of the 1960s and 1970s was not the Soho we know today: it was gritty and rough and not a desirable place to live. With its seedy, industrial lofts with shared—or often nonexistent—facilities, the low rents, and “anything goes” attitude, it became a haven for artists. However, even as people moved into the area it was still dirty and dangerous. There weren’t many places to get the basics, including food, as it was an industrial district lacking restaurants.

Gordon Matta-Clark and Carol Gooden changed that when they opened Food in 1971. It was a community restaurant staffed by artists, with rotating menus and innovative ideas. It offered a seasonal menu, open kitchen, guest chefs, and even sushi—long before any of those ideas became trendy.

Matta-Clark came from a family of artists. He studied architecture at Cornell, and his work often consisted of “building cuts” where he would remove sections from the structures of abandoned buildings, carving holes in the floor or removing walls. His environment was his canvas, so as a cook his meals became art pieces. He was known for some rather funky creations, such as the whole fish he gelled in black aspic and then jiggled for diners, making it appear as though the fish was swimming. He once hosted a bone dinner that consisted of frog legs, oxtail, and other bony items. At the end of the evening, the leftover bones were washed and strung on necklaces for guests to wear as a souvenir.

Food was started more as a community hub than as a restaurant venture. It earned a good review by Milton Glaser in New York Magazine and became popular even outside of the art community, but the owners gave it up it after only three years in business. Matta-Clark died only a few years later in 1978 at 35 years old from pancreatic cancer, two years after his twin brother committed suicide.

It’s fair to say that Matta-Clark and Girouard’s idea was ahead of its time. Some of the tenets that made Food so unique are currently in the culinary spotlight: we see food as art in our social media and high-end restaurants, we see experimentation and exchange of ideas in culinary startups and incubators, and we see community restaurants that provide jobs to the underprivileged. Today the Food building houses a clothing store with no trace of the old restaurant that was once a hub to the artistic community.

| 1971 | Food Restaurant opens |

| 1974 | Carol Gooden and Matta-Clark sell the restaurant |

| tidbit | Gordon-Matta Clark |

| internal | Gordon Matta-Clark - Wiki |

| article | NY Times: When Meals Played the Muse |

| internal | 1972 New York Magazine Review |

| internal | Soho Memory Project: Food, Glorious Food |

| sight | The Banquet Years |

| internal | Food Documentary |

| internal | GoogleDoc |

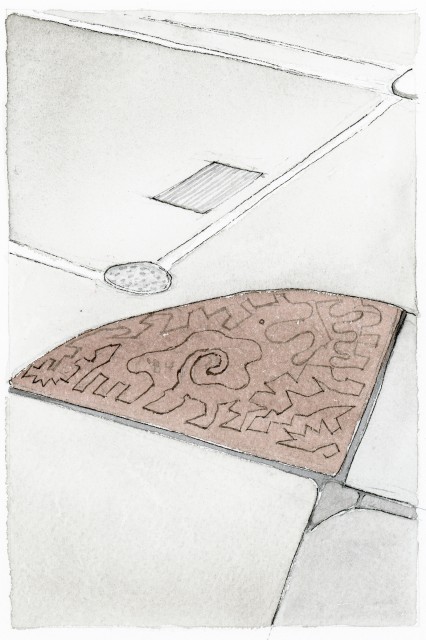

Look down and you’ll see one of Ken Hiratsuka’s pieces etched into the sidewalk. The maze-like carvings at the corner of Prince and Broadway started part of a guerilla art movement he called One Line Sculptures that works its way through natural stones and public sites across the globe. Together, all the pieces around the world reduce the earth to one huge rock. All the works are fluid and free—part of the dichotomy of working on rocks. The only rules are that each piece is created from one line, and that the line never crosses itself.

The piece at Prince and Broadway holds a special place in the series because it was the first one. It was done covertly over many nights, with one eye on the art and the other looking out for the law. As Ken explained to us, the piece almost wasn’t completed. One night his friend, Toyo Tsuchiya, came with him to shoot photos of the process when suddenly they noticed a light flashing in front of them. The police had driven up the one-way street the wrong way and caught them by surprise. Ken told us:

“I dropped the hammer and chisel and rubbed the powdery white surface of the granite sidewalk with my hands. I looked at the police woman and smiled, saying hello. She smiled back to me and looked down the unfinished carving on the sidewalk from her driver’s seat of the police car. She did not say a thing. She turned around and left me and my photographer on the sidewalk. I could not believe it. Magical relief flooded me, and my shoulders lightened… I went back some more times to the sidewalk and finally finished the carving on that corner 1984 October. It took me one year to finish this corner.”

The line between art and vandalism is often blurred, and this piece—which started as sidewalk graffiti—is now a landmark in the neighborhood. Each day, it is changed by the wearing of thousands of people stepping over it, snow melting into it, sun lightening it, and other environmental factors.

Ken has other pieces from the One Line series in the area, each evoking unique imagery, such as Keith Haring’s cartoonish outlines or prehistoric cave drawings. A few pieces were commissioned by Tony Goldman of Goldman Properties, like the large carving in front of 25 Bond that is often described as wavelike, perhaps due to the oceanic curves of the building across the street. As Ken says, “I want to inspire people to become more conscious of nature and our common humanity… In my art there are no social, economic, cultural or political distinctions. We are all one.”

| 1984 | Ken Hiratsuka finishes sculpting sidewalk art on Prince & Broadway |

| tidbit | Tony Goldman |

| sight | Bond Street |

| link | Ken Rock Official Website |

| article | Underfoot, Artist at Work |

| article | 25 Bond Gets Rocked by Chiseler Ken Hiratsuka |

| internal | gDoc |

| internal | Ken Hiratsuka Finding the Heartbeat of a Stone |

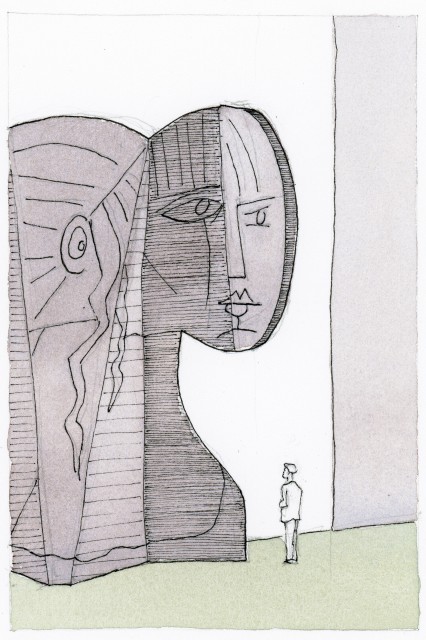

As we cross Houston Street, the neighborhood changes from the frenetic pace of Soho—with its ornamental cast iron buildings—to the academic campus of New York University and these three giant, undecorative concrete structures, called the Silver Towers. The towers, their landscaping, and the Picasso sculpture they enclose are known as University Village and were designed and commissioned in the 1960s by I. M. Pei, who later went on to become most famous for the glass pyramid of the Louvre in Paris.

I.M. Pei created the Silver Towers in a style that became knows as brutalism, which some find harsh and others appreciate for its functionality. Brutalist buildings tend to use exposed concrete and modular elements, and the functions of the buildings are often expressed on the exterior rather than hidden behind a facade. They were popular in the 1950s through the 1970s for government and institutional buildings because they tend to communicate strength and functionality. The Silver Towers were originally planned as student housing, but as part of the purchase deal NYU was required to designate one of the buildings for subsidized housing.

Pei himself requested the Picasso sculpture in the middle, called Bust of Sylvette. After the developer of another project he was working on vetoed having a sculpture there, Pei decided to put it here instead—a fitting choice since the piece uses the same concrete materials as the buildings but in a much more fluid, artistic way. Coincidentally, the project that rejected the sculpture was in the Kips Bay area of Manhattan, where Peter Cooper’s glue and cement factory once stood.

Sylvette was one of Picasso’s many muses throughout his career. She was 19 years old when they met, with a tall, bouncing blonde ponytail that caught Picasso’s attention. Their relationship of artist and muse was only platonic, which was unusual for Picasso, and it lasted only a few months. However, it was a prolific time in Picasso’s career, and he produced more than 60 Sylvette-based pieces of various media in the short time. The pieces were exhibited in Paris in the summer of 1954 to rave reviews, inspiring Life magazine to call the era Picasso’s “Ponytail Period.”

Norwegian sculptor Carl Nesjär worked with Picasso to create the Bust of Sylvette, which is based on one of Picasso’s much smaller, folded sheet metal sculptures. Picasso assisted Nesjär with the sculpture, but he never visited the space where it sits today. Here we call it a Picasso because that is what New York University etched into the plaque, but Sylvette inspired it, I. M. Pei decided to install it, and Nesjär made it—which raises questions about where inspiration starts, what defines an “original,” and the politics of who deserves credit.

We at ArtWalk have varying opinions about this piece: some feel it is a true Picasso, while others consider it a piece inspired by Picasso but ultimately call it a Nesjär.

| 1949 | Housing act signed |

| 1967 | Constructed by Carl Nësjar, Silver Towers open |

| 2008 | Designated a National Historic Landmark |

| link | Pablo Picasso |

| link | Carl Nesjar |

| link | SoHo Memory Project: Two Towers |

| link | Artlyst – Sylvette |

| link | The Dezeen Guide to Brutalist Architecture |

| internal | Pablo Picasso - Wiki |

| internal | Brutalist Architecture |

| internal | University Village, NYU |

| internal | Wiki Sylvette |

| internal | Learn About the Artist: Sylvette David |

| internal | Picasso.org – Sylvette |

| internal | University Village, New York |

| internal | Washington Square Village |

| internal | gDoc |

using the same materials with so different effects, the fuzzy border between original, inspiration, and copy

Developer have significant impact on the city, next up we’ll look at another developer who had a very different point if view.

Robert Moses & Jane Jacobs

Haughwout Building

Cast Iron Facade Mural

Today 76 West Houston is a condominium, but the famous street has have witnessed one of the most well known and controversial artists of the twentieth century. Jackson Pollock moved here with one of his brothers in 1934. The apartment they moved into above a lumber yard was unheated and ran only cold water. At the time, Pollock made his living as a janitor at a nearby school and as ”Stone Cutter” for the Emergency Relief Bureau, an organization created by the Hoover administration to get people back to work. More lofty sounding than it was, his job as a stone cutter was in fact to clean and maintain the statues in public parks – one of those being the statue of Peter Cooper at Cooper Square.

He stayed in this apartment for only about a year, living in different homes throughout the 1930s and early 1940s while he studied art and continued painting. Pollock eventually worked for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, which supported artists such Mark Rothko, José Clemente Orozco, and Willem de Kooning.

In the early 1940s, Peggy Guggenheim took notice of Pollock’s art and commissioned him to make an 8-foot tall by 20-foot long mural for the entryway of her townhouse. This led to Guggenheim’s patronage of Pollock, which allowed him to paint full time. Then a 1950 spread in Life Magazine catapulted Pollock to fame. Although he was securely established as an artist, the sudden fame caused critics to question Pollock’s authenticity to the point that he himself started to have doubts. Always a troubled man and heavy drinker, Pollock’s marriage unraveled in 1956, and that August he died in a one-car alcohol-fueled accident, killing himself and a fellow passenger.

Pollock explained his art by saying it represented his “inside world.” He said if viewers wanted to see real objects, they could look at them; his art, on the other hand, was motion and energy. His works often have a sense of immediacy, as though they are a direct translation from thought or feeling to paint without the burden of perfection—an appropriate interpretation for art painted in a city that constantly moves with energy.

| 1930 | Pollock moves to New York |

| 1934 | Pollock moves to 76 W Houston, an unheated apartment above a lumberyard |

| 1935 | NYC Emergency Relief Bureau hires Pollock to restore public monuments |

| 1943 | Pollock earns solo show run by Peggy Guggenheim |

| 1945 | Pollock moves out of New York but still paints full time |

| link | Jackson Pollock |

| link | MoMA - Jackson Pollock Chronology |

| link | The Works Progress Administration (WPA) |

| internal | Jackson Pollock - Wiki |

| internal | Works Progress Administration - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

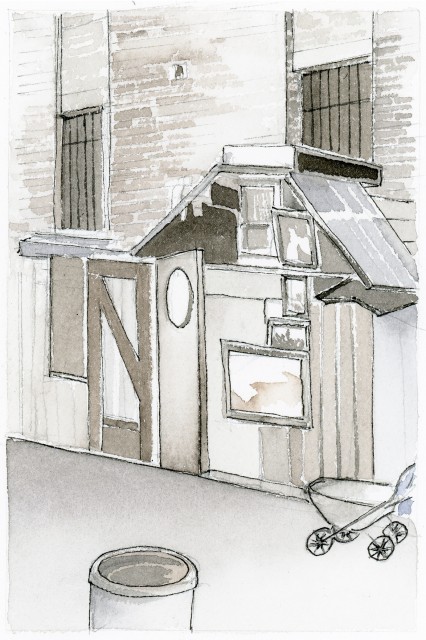

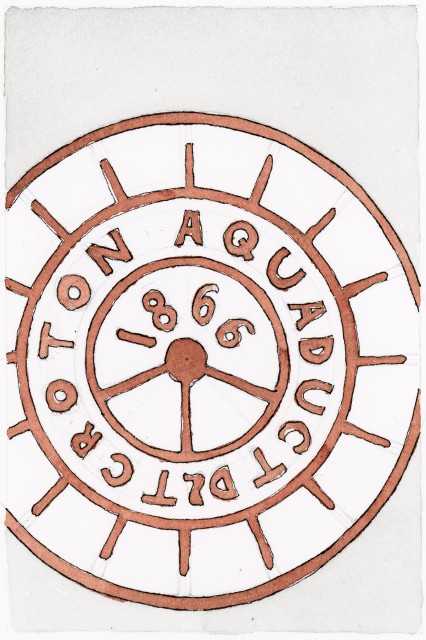

While strolling through busy Soho, it’s easy to overlook tiny Jersey Street, a little trafficked side road that takes us back in time. And on this street, it’s even easier to miss a small artifact that embodies a vital part of New York City history and its growth: at the southern end of the Puck Building—which was a printing plant for more than a century and turned out publications such as New York Press, Spy Monthly, and Puck Magazine—almost hidden under modern asphalt, is New York City’s oldest manhole.

The manhole cover reads “Croton Aqueduct” and “1866” – that’s not the serial number, but the year – which was before boroughs were created. After the introduction of the five boroughs in 1898, manholes in Manhattan were imprinted with “MANHATTANBOR,” and a few of those can still be spotted as well.

Today we think of manholes as leading to our sewage system, but this one has the word “aqueduct.” In fact, it led to New York City’s fresh water supply. After the Collect Pond was drained in 1810, a new source of water was needed, so the Croton Aqueduct was built. Completed in 1842, it supplied New Yorkers with drinking water from the Croton River, 41 miles to the north. The aqueduct brought water into a reservoir on 42nd Street, through which it was distributed to the city. The reservoir was surrounded by 50-foot (15-meter) walls that were 25 feet (7.6 meters) thick. These walls offered space for public promenades on the top, and Edgar Allen Poe was one of many city residents who could frequently be seen strolling along them.

In the 1840s, New York City’s population was just over 312,000. Within just 50 years, the city had ballooned to more than a million people, outgrowing the reservoir. A dam was built on the Croton River, making the reservoir obsolete. It was torn down in the 1890s, and in its place now stands the research branch of New York Public Library and Bryant Park.

It’s fascinating to think about the change, the people and the ideas that shaped New York in these brief 200 years. In a city of extreme impermanence, as we experience it today with its inhabitants rushing and shoving, it’s comforting to know that some ideas persisted. Not only did the ideas persist but the actual work, objects, sculptures, and buildings are still here today to tell us the stories of the past.

| 1842 | Water starts flowing into New York from Croton River |

| 1899 | Croton reservoir demolished |

| wiki | Croton Distributing Reservoir |

| link | Book: Waterworks by E.L. Doctorow |

| internal | Oldest New York Manhole |

| internal | Forgotten NY - Jersey Street |

| internal | The Waterworks - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

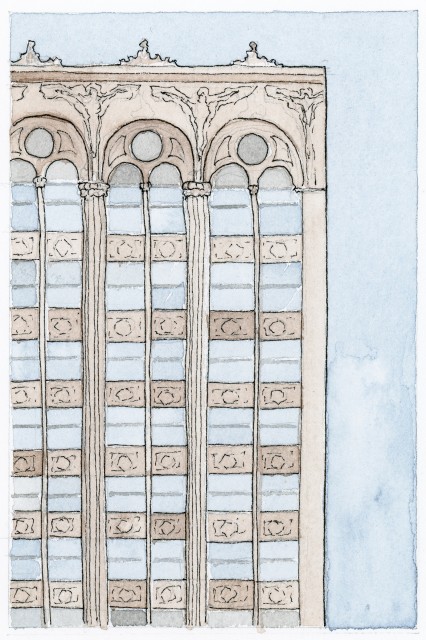

In a city famous for high-rises, it’s surprising that the man known as the “father of the skyscraper” constructed only one building here. The 13-storey Bayard Condict Building is humble by today’s standards, but during its construction in 1897, Louis Sullivan was known for creating some of the tallest buildings in the world.

The Bayard Condict Building, commissioned by United Loan and Investment and named for one of New York’s prominent families, is an important one both in Sullivan’s career and in the history of New York City. Sullivan moved away from the old standards of architecture at the time, creating one of the first steel skeleton framed buildings and covering the masonry with detailed terra cotta reliefs, an architectural innovation at the time that allowed for intricate facades to be mass produced. The vertical columns that are accentuated on the facade emphasize the height, and the higher-than-usual ratio of window to structure was a harbinger of today’s fully glass facades.

Unfortunately for Sullivan, stepping away from the norms of the times caused the Department of Buildings to raise many objections. Plans were adjusted many times, even throughout construction, before the building was completed in 1899. Ownership had transferred three times within just a few years, resulting in the name changing from The Bayard Building to The Condict Building and then back again to its original moniker.

101 years later, in 2000, the building was restored by WASA/Studio A, a New York-based architecture and engineering firm. During the restoration, each of the 7,000 glazed architectural terra cotta tiles was inspected, and only 30 were found to be damaged beyond repair.

Sullivan’s legacy included not only the skyscraper, but also a well known credo still used throughout the design world today: “Form ever follows function,” which we know more familiarly as “form follows function.” Although his contributions are widely respected now, in his lifetime his innovative ideas and architectural business frequently struggled. When he died a penniless alcoholic in 1924, it was his more famous protege, Frank Lloyd Wright, who paid for his funeral.

| 1897 | Construction begins |

| 1899 | Construction finishes, building opens |

| 2000 | Restoration overseen by WASA/Studio A |

| article | People & Events: Louis Sullivan (1856-1924) |

| link | Chicago School of Architecture (c.1880-1910) |

| internal | Sullivan Building (Bayard-Condict Building) - Wiki |

| internal | Louis Sullivan - Wiki |

| internal | Chicago School - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

It’s hard to miss The Wall, an 8-storey high facade at 599 Broadway overlooking Houston Street to its north. The bright blue wall supports 42 green aluminum bars bolted to steel braces, looking like an army of plastic army ships at sea or a large, predictable Plinko board.

This piece is also known as The Gateway to Soho, and it was created by Forrest “Frosty” Myers first in 1973, and then again 24 years later. He first made it for a small commission of $2,000 from City Walls, Inc., a group of artists that transformed several blank facades into artworks throughout the 1970s.

While the group is no longer around, much of their art still exists—but it’s not always easy to keep it up, both financially and literally on the wall. This piece was almost lost in 1997 when the building’s owners complained to the Landmarks Preservation Commission that the artwork had caused leaks and structural damage to the building. After a lengthy legal battle, a compromise was reached: the art would be removed during the renovation of the building, then reinstalled 30’ higher so the bottom of the wall could be used for advertising space.

This compromise made sense. Back when the work was originally created, City Walls, Inc. simply asked the building owner for permission. Soho was a different area in the 1970s, and nowadays it would be nearly impossible to convince a Soho building owner to sacrifice advertising space in one of the world’s most famous neighborhoods for art.

Although many of Frosty’s sculptures are large, one of his most intriguing works is tiny: the “Moon Museum” is a ¾ inch x ½ inch ceramic tile initiated by Frosty and containing a drawing by him, Andy Warhol, and each of four other artists. Rumor has it the piece was sneaked into the Apollo 12 space mission of 1969 and left on the moon, creating the first “museum” in space.

| 1973 | Installed |

| 1997 | Owners of 599 Broadway file complaint with city over artwork |

| 2002 | Removed for building repairs |

| 2004 | City sued 599 Broadway owners to replace artwork |

| 2007 | Re-installed |

| tidbit | Moon Museum |

| sight | Houston Street Expansion |

| link | Forrest Myers |

| internal | The Wall - Wiki |

| internal | The Village in 2005 on the re-installation |

| internal | gDoc |

| internal | SoHo Memory City Walls to City Malls |

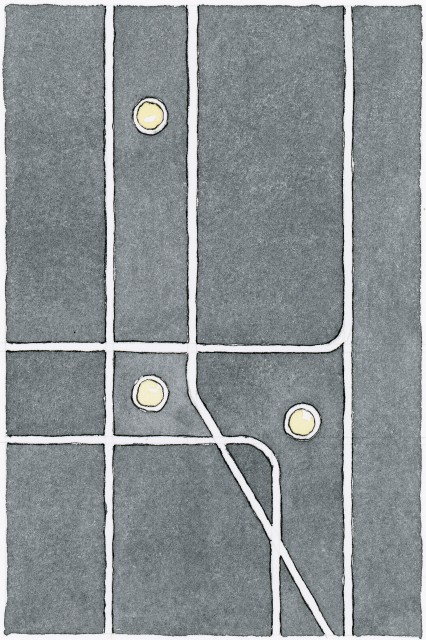

“Subway Map Floating on a NY Sidewalk” by Francoise Schein intertwines the past and the present in its circuitous depiction of Manhattan subways. Prior to the city taking over transit in the 1940s, the lines were run by private companies. Transit history buffs are familiar with Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT), which built what we currently know as the 1,2,3 and 4,5,6 routes. Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit (BMT) covered parts of Brooklyn and lower Manhattan, including what we know today as the L. And the Independent Subway (IND) came along in the 1920s and built what we now know as the A/C and B/D routes running along 8th and 6th Avenues, respectively.

In this piece, Francoise blends aspects of all of these networks with today’s system to produce a map that—while not useful to the average straphanger—contains a history of the city hidden in each of its stainless steel bars and illuminated glass circles.

Additionally, her works all carry a theme of human rights. This one, commissioned in 1985 by Tony Goldman of Goldman Properties and spanning 90 feet x 12 feet, represents that the subway is the ultimate democratic place to reach the people. Following this work, Francoise went on to create a piece for the Concorde station in Paris that contains the entire text of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Man on tiles around the interior.

She even founded a nonprofit that creates art and events around Europe to start discussions on human rights principles and cultural diversity. As she explains: “I have come to see cities and villages as living beings who tell stories of the lives that have crossed through and in them, thereby leaving indelible marks on the successive strata of the city’s foundations. My projects pay homage to that reality.”

| 1986 | Installed by Francoise Schein |

| tidbit | Tony Goldman |

| link | Subway Map Floating on a New York Sidewalk |

| link | SoHo Landmarks |

| internal | gDoc |

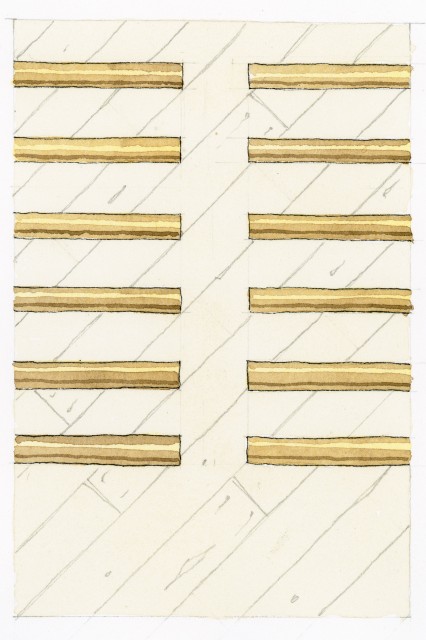

Hidden at 393 West Broadway is a piece that many New Yorkers don’t even know exists. It’s an installation by Walter De Maria that takes up an entire loft and has been maintained by the Dia Foundation since 1979. It consists of 500 meticulously aligned brass rods, each two meters long, adding up to one complete kilometer in length.

De Maria is known for his minimalist art, usually made of simple geometric shapes often produced by industrially manufactured materials. Another seminal piece of his is The Lightning Field, a one kilometer by one mile grid of 400 stainless steel poles in New Mexico. The Broken Kilometer and Lightning Field are two pieces of a four-part series of large installations. The other two are The Earth Room in Soho and the Vertical Earth Kilometer in Kassel, Germany. The Vertical Earth Kilometer is a sister to this piece and consists of a similar solid brass rod extending one kilometer into the earth, the only visible part being one end that is flush with the ground.

Rarely explaining his work, De Maria’s art uses shapes and concepts that we see and use every day, like distance or soil, but he rarely explained his intentions behind his work. He wanted the viewer to read and understand the shapes as a visual language. The element of trust is also very important in his work as it requires the viewer to buy into his ideas, almost participate and have us reflect on all the other things we trust on a daily basis without thinking about.

While the shapes and textures seem basic, a closer look shows more contrast in his overall sense of the art experience. For instance, he was also a musician, playing music that could be considered must less restrained than his art. He was in a few bands, most notably The Primitives, which later became rock band The Velvet Underground in the post-De Maria years.

DeMaria continued to create installations around the world until he passed away in 2013, leaving us to wonder about his unchanging works and their meanings in an ever moving world.

Note that The Broken Kilometer is open Wednesday through Sunday from 12pm-6pm (closed 3:00-3:30pm). It is also closed through the summer from mid-June through mid-September. Admission is free.

| tidbit | Walter De Maria |

| sight | The Earth Room |

| internal | Walter De Maria |

| link | Thirty Years of Eternity |

| internal | Walter DeMaria - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

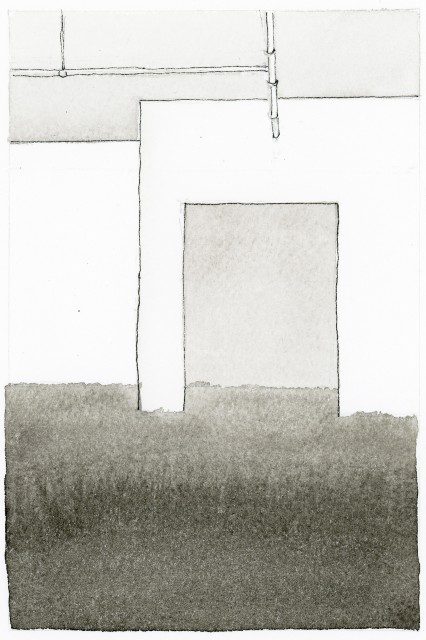

In the middle of the modern, manmade neighborhood of Soho, a residential building hides something rarely—if ever—found indoors. As you enter the building and start up the stairs to the second floor, the smell of damp soil infuses the air. The Earth Room, an installation at 141 Wooster created by Walter De Maria in 1977, is an apartment full of knee-high natural earth.

The nature-inspired work is striking to see in the middle of our concrete jungle. De Maria was very particular about the color of the earth, and the dirt you see today has not been replaced—it’s the same earth that he selected in 1977. Earth is vital to life, yet it’s easy to live a life free of mud and dirt in a city as concrete as New York. The Earth Room asks us to question how nature fits into our lives. Do we find it comforting to see the outdoors inside, or is it confusing? In a world where we take our shoes off to enter a house, the Earth Room reverses our expectations.

This piece is one of four in a series of large installations by De Maria. Another of the four, The Broken Kilometer, can be seen a short walk away at 393 West Broadway and consists of 50 two-meter rods carefully arranged to represent the title of the piece. The Vertical Earth Kilometer, a kilometer-long rod dug into the ground, is in Kassel, Germany. And Lightning Field, in New Mexico, is a one kilometer by one mile grid with poles pointing skyward.

This Earth Room is the only one of three Earth Rooms made by De Maria that is still in existence. The 280,000 pounds of dirt (127,000 kilograms) required structural reinforcements in the building, and it is maintained by the Dia Foundation. They ensure the soil is raked and watered weekly to keep it looking as fresh as it was upon installation.

Note that The Earth Room is open Wednesday through Sunday from 12pm-6pm (closed 3:00-3:30pm). It is also closed through the summer from mid-June through mid-September. Admission is free.

| 1977 | Earth Room Installed |

| 1977 | Jimmy Carter becomes president |

| tidbit | Walter De Maria |

| sight | Walter De Maria's Studio |

| sight | The Broken Kilometer |

| internal | Walter De Maria |

| internal | Walter De Maria - Wiki |

| internal | Washington Post: Escapes: 'The Earth Room' and Other Art by Walter De Maria in New York |

| internal | gDoc |