Much of what you see as you look at the Brooklyn Bridge depends on where you stand.

Look at it architecturally and you’ll notice its piers: Constructed of limestone and granite with gothic arches, they stand 276 feet and 6 inches above the high water line, 117 feet above the roadway. (Some believe that when the bridge opened on May 24,1883, the piers were the tallest structures not only in New York, but also in the Western Hemisphere. However, the 281-foot spire of Trinity Church, built in 1846, was higher.)

Look at it as an engineering feat and you’ll concentrate on its wire cables. Each of the four steel cables that support the 85-foot wide bridge deck measure 15 ¾ inches in diameter and 3,578 feet, six inches in length. Each cable consists of 5,434 individual wires with a total length of 3,515 miles protected by 243 miles, 943 feet of wire wrapping. Each one weighs 1,732,086 pounds. These cables enabled John Roebling, the designer and builder of the bridge, to build the first steel suspension bridge spanning a record 1,595 feet, 6 inches.

If you look at it in human terms, you’ll consider that between 20 and 30 people lost their lives building this bridge. John Roebling was among them. While conducting survey work for the Brooklyn pier, his foot was pinned against a dock by a ferry. After a few weeks of ineffective self-treatment, on July 22, 1869, he died from tetanus. His son, Washington Roebling took over construction. He got the bends from ascending too quickly in the caissons used for under-water excavation. He was paralyzed for the rest of his life. He viewed construction through a telescope from a window of his house in Brooklyn Heights while his wife, Emily, managed the construction on-site. By the time the bridge was completed, many assumed she was the chief engineer. When the bridge was completed, Emily was the first to ride over it.

Six days later, on May 30, 1883, an unprecedented number of people crossed the bridge on foot. A woman stumbled on the stairs, shrieked and started a stampede of people who feared the bridge was collapsing. Twelve were trampled.

If you look at the bridge in animal terms, you’ll find that on May 17, 1884, P. T. Barnum led 21 elephants, including Jumbo, from Manhattan over the Brooklyn Bridge, proving that it was strong and stable and putting to rest the fears that triggered the stampede. Today the bridge is home to some of the estimated 20 pairs of nesting peregrine falcons that live in New York.

If you look at it through an artist’s eyes, you’ll see not only a “physical bridge that stands astride the East River,” but a cultural bridge “of the mind and the imagination.” That bridge stands in the writings of Hart Crane and in the photography of David Hockney, to name only two who have been inspired by the sight of the Brooklyn Bridge.

– Carol Cofone

| 1867 | John Roebling presents design for bridge across East River |

| 1869 | John Roebling is injured and dies of tetanus |

| 1872 | Washington Roebling incapacitated by "caisson disease” |

| 1883 | Bridge completed |

| tidbit | Bridge Jumpers |

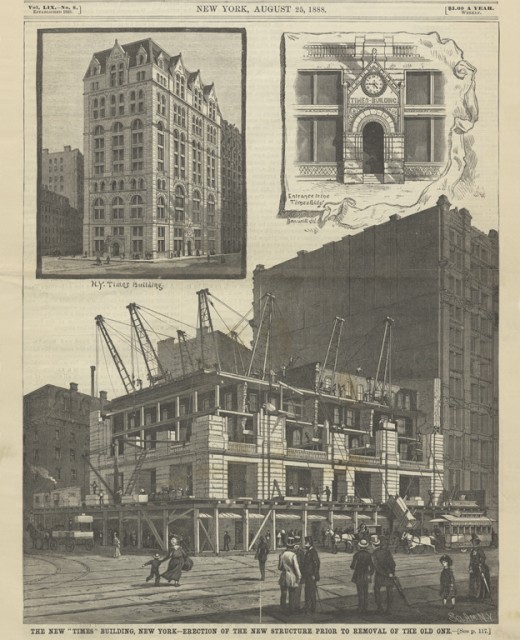

New Yorkers move. Often. Each neighborhood, street and building we live in says something about us. The New York Times is no different. Like many New Yorkers, its first digs were humble. On September 18, 1851 it began publishing at 113 Nassau Street between Ann and Beekman Streets in the Financial District. Known then as The New York Daily Times, it occupied an unfinished fifth floor loft. The gaslight fixtures had not been installed, so editors and reporters worked by candlelight. Since the windows hadn’t been installed either, the breeze blew out the candles.

The New York Times didn’t stay there long. In 1854, it moved one block and rented 138 Nassau Street at Beekman Street. Only four years later, it moved another block to 41 Park Row at Spruce Street, where it built The New York Times Building, the first specifically constructed to house a newspaper in New York. The five-story stone building was designed by Thomas R. Jackson, a prolific if unsung architect known for purpose built projects, in the Romanesque Revival style.

In the 1870’s The Tribune built a taller building. In 1888, the Times responded. George B. Post, a celebrated architect-engineer known for pushing the boundaries of design for commercial projects with new requirements, was commissioned to design a grander – and of course taller – Romanesque building. Thirteen stories, with Maine granite and Indiana limestone arches, were constructed around the core of the original building. In 1896, Adolph Ochs bought the paper and hired Robert Maynicke to remove the original mansard roof and add three additional stories. The building, owned by Pace University since 1951, is the oldest survivor of what was once “Newspaper Row.”

In 1905, The New York Times departed Printing House Square to move to Midtown. It arrived at what had been known as Long Acre Square, a neighborhood of rooming houses, small factories and questionable entertainment. This lent a cachet (which has waxed and waned over the years) to the newly renamed Times Square to rival that of Herald Square, its competitor’s location a short walk south on Broadway.

This was not the Times last move. Since 1904 The Times has occupied three major midtown locations, including The Times Tower at 1 Times Square, the Times Annex, and its current home at the New Times Tower at 620 Eighth Avenue, as well as its virtual location that adds on 350 more stories each day.

— Carol Cofone

| sight | NYTimes: The Signs of the Times |

| sight | NYTimes: All Centuries Come to an End |

| sight | NYTimes: A Glass House |

| sight | Moveable Type |

Standing in front of 122 Chambers Street, you are unlikely to be reminded of the opulent Gilded Age. But this property was once part of a highly desirable residential district in the City. It was where one of New York’s most fashionable families lived – a family so dominant it may have inspired a very well known English saying.

Around 1806 leases were expiring on properties owned by Trinity Church on Chambers, Warren and Murray Streets. Trinity’s new terms required leaseholders to erect substantial brick or brick-fronted houses within a window of time. These new leases prohibited hazardous uses, and so, in an early episode of gentrification, artisans were forced out. Well-to-do merchants and professional men and their families moved in.

One fashionable couple – Isaac Jones, third president of Chemical Bank, and his wife, Mary Mason Jones, daughter of John Mason, second president of Chemical Bank and a founder of the New York and Harlem Railroad (part of today’s Metro North Railroad) – built and moved into a rowhouse at 122 Chambers Street in 1818. It was gas lit, and much admired as the first New York house with a bathtub. (Details on the bathtub are scarce but it must have been enviable since it was mentioned in her 1891 obituary in The New York Times.)

However, the spread of commerce around Chambers Street spurred an exodus of wealthy residents from the area. The couple moved north and Mary’s real estate ventures became more ambitious. As her grand-niece, the novelist, Edith Wharton, explained “In those days the little “brownstone” houses…marched up Fifth Avenue…in an almost unbroken procession from Washington Square to the Central Park…The most conspicuous architectural break… occurred…at the awkwardly shaped entrance to the Central Park…[where] our audacious Aunt Mary…erected her own white marble residence…I doubt whether any subsequent architectural upheavals along that historic thoroughfare have produced a greater impression.” Impressions such as these fueled the phenomenon, and inspired the expression, of “Keeping up with the Joneses.”

Not many could.

This was not Wharton’s most famous accounting of her Aunt Mary’s real estate ventures. Mary was the model for Mrs. Manson Mingott in the book, The Age of Innocence. Published in October 1920, the bestseller won the Pulitzer Prize in May 1921. Though Mary died in 1891, this book made her immortal. You couldn’t keep up with her even after death.

Today 122 Chambers bears little resemblance to Mary’s original rowhouse. It was inherited by Isaac and Mary’s daughter, Emily. Between 1857 and 1858 she redeveloped the property as the Italian Renaissance Revival store-and-loft building that stands today. The ornately-carved ornamentation on its arched lintels, still visible today, represented a more decorative alternative to other palazzo style buildings which had simpler molded surrounds. Add to this the building’s caramel-colored Dorchester sandstone and you have a “conspicuous architectural break” still noticeable today. Mary Mason Jones would approve.

— Carol Cofone

| link | Amazon: The Age of Innocence |

| wiki | New York City Hall |

At almost 250 years old, St. Paul’s Chapel has seen and survived it all: the American Revolutionary War, the Great Fire of New York (1776), George Washington’s Inauguration, and 9/11. The Chapel is the oldest surviving church in Manhattan and the oldest public building in continuous use in New York City.

After Trinity Church was destroyed by fire in 1776, St. Paul’s became the center of worship in the small city. President George Washington worshipped at the church during the two years that New York served as the nation’s capital, including his Inauguration Day in 1789. George Washington’s original pew can be seen in the chapel, with the original rendition of the seal of the United States hanging above it. The church’s interior is mostly unchanged from the early 18th century, with the glass chandeliers dating back to 1802 and the organ dating back to 1804.

The church played an important role yet again in the city over two centuries later on September 11, 2001. After the Twin Towers–which stood just across the street from the Chapel–were hit, St. Paul’s served as a refuge for the victims of the attack. Doctors and volunteers gathered in the church to provide medical attention to the hurt and also handed out food and water. After the attack, the chapel became a makeshift memorial for those lost.

Miraculously, the church was unscathed, with not even a broken window. Only the organ experienced problems, with its pipes having been damaged by the smoke and fire in the air. It was soon refurbished and is now working again. What ultimately saved the church was the huge sycamore tree that stood in front of it. The tree’s massive branches caught all of the falling debris that may have destroyed the structure. The tree is no longer standing, but a bright red cast of its twisting roots sit outside of Trinity Church.

St. Paul’s Chapel has been a city landmark since 1960.

| sight | Trinity Church |

| tidbit | The Great Fire of New York |

| internal | Wiki |

On the morning of August 7 1974, 24-year-old Philippe Petit finally performed the daring stunt that he had spent six years planning: a high-wire walk between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

Petit first got the idea while looking through a magazine at the dentist in 1968 when he was just 17. Photographs of the not-yet-completed buildings captivated him, and he was seized with the desire to perform there. The artist collected articles on the Towers whenever he could, and learned everything about the buildings and their construction in preparation for the performance. Although his walk across the Towers is Petit’s most famous performance, it was not his first high-wire stunt. While planning for his walk between the Towers, he began performing at other famous places such as the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris and the Sydney Harbour Bridge in Sydney, Australia.

With his friends’ help, Petit was able to study the Towers and scope out the site. From renting helicopters and taking aerial photos of the unfinished buildings to sneaking into the Towers and studying the building’s security measures, Petit’s collaborators played major roles in the success of the performance.

Petit went to extreme measures to gain access to the building, from fake IDs and construction outfits to posing as a journalist from a French architecture magazine. Although he was once caught on the roof by police, he continued forward with his plans.

On the night before the performance, Petit and his crew caught a freight elevator up to the 104th floor. Once on the roof, Petit’s crew used a bow and arrow to shoot the 450-pound steel cable across the void between the two towers.

A little after 7am, Petit began his 45-minute performance 1350 feet above the ground, dancing, walking, and laying down on the cable as the Towers and wire swayed in the wind. While onlookers watched and cheered, the NYPD and Port Authority officers were on the roofs of both towers persuading Petit to come down. Though they threatened to lift him off by helicopter, Petit came down on his own after it started to rain.

Back on the ground, Petit was greeted by news casters, cameras, cheers, and the news that the district attorney would not press charges for the stunt. In exchange for his freedom, the artist was required to give a free performance for children in Central Park. He performed a high-wire walk above Belvedere Lake.

Despite the illegality of his World Trade Center performance, Port Authority gave Petit a lifetime pass to the World Trade Center Observation Deck, where he autographed a steel beam close to the spot where he began his walk.

Since September 11, 2001, Petit has performed numerous times in Central Park to commemorate his Tower walk and to remember those lost in the attack. “It’s painful to perform here now with them gone, but I still consider them my towers,” Petit told the New York Times in 2005. “If they built them again, I would walk between them again.”

In 2008, director James Marsh explored Petit’s planning and stunt in “Man on Wire,” a documentary based on Petit’s book of the same name.

| 1968 | Petit begins planning his walk |

| 1974 | Petit walks between the Twin Towers |

| 2001 | The Towers are destroyed |

| 2008 | "Man On Wire" documentary is released |

| internal | gDoc |

| link | Man On Wire official site |

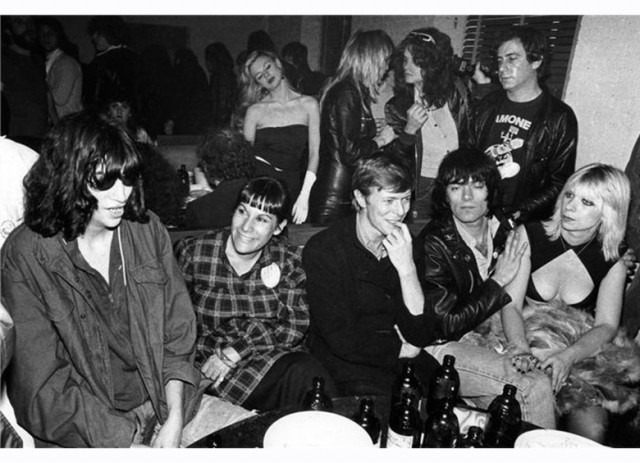

The Mudd Club–named after Samuel Alexander Mudd, a doctor who treated John Wilkes Booth’s broken leg when he fled capture after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination–was opened in 1978. It quickly became a staple in the city’s underground art and music scene and was a hotspot for up-and-coming artists and musicians such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lou Reed, Andy Warhol. David Bowie, Debbie Harry, Nico, and Keith Haring, who was the curator of the club’s fourth floor rotating art gallery. It also served as an important punk and rock music venue, with bands like The Contortions, DNA, and the Talking Heads debuting new albums and compositions on its stage.

The club’s importance in the New York music and art scenes can be seen in the many references made to it in songs: “Life During Wartime” by the Talking Heads and “The Return of Jackie and Judy” by the Ramones both make references to the venue.

Despite its popularity at its inception, club shut its doors in 1983. In 2007, Creative Time, an arts organization, placed a plaque on the building at 78 White Street to commemorate its existence.

| tidbit | Keith Haring |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | Street View |

| article | Anthony Pappalardo on the Mudd Club |

| internal | Wikipedia: Samuel Alexander Mudd |

Valerie Jaudon designed a new paving scheme, entitled Reunion, for the surface of the three-acre brick walkway that connects Police Headquarters with the Municipal Building in Lower Manhattan. Drawing on the plan for the Municipal Building’s original 1910 inner courtyard, Jaudon designed traditional brick patterns of herringbone and basket-weave fields in brick and granite. The red brick sidewalk serves as a frame for inlaid-granite fractured diagonals and overlapping circles 34 feet (10.4 m) in diameter. The artist intended to make the pedestrian traffic passage more human in scale, while preserving the monumental character of the plaza. Art Commission Award for Excellence in Design 1987

Born in Greenville, Mississippi, Valerie Jaudon attended the Mississippi State University for Women, the Memphis Academy of Art, the University of the Americas in Mexico City, and St. Martins School of Art in London. Jaudon has exhibited widely as a painter. Her previous public art projects include metal fencescreens for the NYC MTA, at the Lexington Avenue IRT Subway Station at 23rd Street.

via NYC Culture

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | NYC Culture |

| internal | CultureNow |

The Brooklyn Bridge’s pioneering use of steel cables and a suspended roadway are repeatedly referenced in the design of artist Mark Gibian’s work. Within the west mezzanine a web of cables recalls the graceful forms of the bridge, while overhead a 30-square foot structure, suspended beneath a skylight, frames the cable work. At the turnstiles, three panels that also use cables serve as a functional barrier. For the artist, the “lacy” curves of the panels “echo the beauty of the bridge’s cross-hatched cables and the feeling of flight as it springs across the East River.” The energy of Cable Crossing suggests “the controlled power of the subway and its network of metal and concrete that undergirds the city. I wanted to explore movement, using soft curves with hard materials,” Gibian says.

A number of Gibian’s pieces can been seen around New York. His 2008 stainless steel sculpture, Crescendo, is located on the Northside Pier in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. His 2008 Serpentine Structures, made of galvanized steel, sits along the water in Manhattan’s Hudson River Park.

edited from MTA Arts & Design

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | CultureNow |

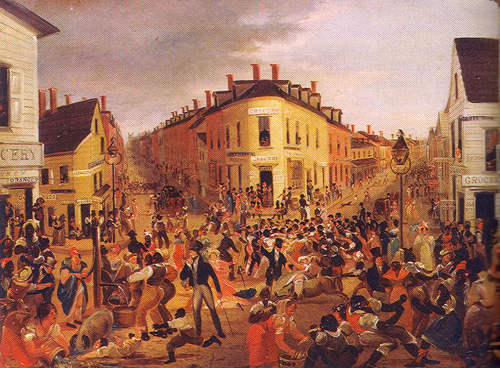

The intersection of Mulberry Street, Worth Street, Park Street, Baxter Street, and Little Water Street (which no longer exists) was known throughout the 19th century as a neighborhood infused with crime, gangs, and run-down tenements.

Because it was built over the Collect Pond and the nearby swampland, the area’s wood frame houses began tilting over and sinking as the landfill started to decay in the 1820s. It soon became infested with disease and mosquitoes, resulting in a mass exodus. Those few who remained fell into poverty and became victims of ruthless crimes, gangs, and slum lords. The neighborhood is said to have sustained the highest murder rate of any slum in the world.

Five Points is considered by many to be the original American melting pot, consisting primarily of newly emancipated African Americans and and Irish minority. Their coexistence in the neighborhood was the first large-scale racial integration in American history. Racial integration played a critical cultural role, having gave way to tap dancing and to a music genre that was the precursor to jazz.

| sight | Collect Pond |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | New York's Most Notorious Neighborhood |

| internal | 5 Points |

Though Federal Plaza now sits empty, it was once the home of the artwork that sparked what is often cited as the most infamous public sculpture controversy in all of art law. Its removal questioned artists’ rights, and the strong negative public reaction that it caused raised important questions about artistic freedom, the role of public art in society, and the role of the community in art.

Serra’s work was commissioned by the General Services Administration’s Art-in-Architecture (GSA) and was chosen for the installation by a panel of curators and art critics. His sculpture–a 120-foot-long, 12-foot-tall continuous Cor-Ten steel wall–cut through Federal Plaza, creating a new space in the pre-existing one. Only two months after its installation in 1981, however, a petition was started by federal workers to remove the Arc, claiming that Serra’s work “ruined” the Plaza and made the space unenjoyable and attractive. They said that Tilted Arc was ugly and threatening, and that it was a nuisance to walk around. They also complained that there was no public input on the choosing of the piece and that they couldn’t understand how so much money ($175,000) could be spent on a “rusted metal wall.”

Public criticism eventually died down, but GSA Regional Administrator William Diamond saw the piece as a way to gain more political power. He soon began speaking out against the piece, claiming that it

was destructive to the plaza’s social space and unsuccessfully tried to have the Arc removed and relocated. Although he claimed that he was not criticizing its aesthetic qualities, he ordered that a petition be put up in the lobbies of the two federal buildings that surrounded the Arc for any person who thought that Serra’s work had “no artistic merit.” By creating controversy around the piece, he would appear as a “man of the people” after its removal and would be known as the hero who took down Tilted Arc.

In 1985, Diamond held a public hearing in order to decide the fate of the piece. Artists such as Frank Stella, Mark di Suvero, Donald Judd, and Louise Bourgeios attended the hearing to testify along with Serra in favor of the piece. Stella argued that the piece was a public good and beneficial to all who could enjoy it. Judd said that art should never be destroyed, and that to destroy Serra’s piece would be sacrilege. “Art is not democratic. It is not for the people,” Serra himself said. He also argued that to remove his work–which he was told would be permanent–without his permission would be to violate his rights as an artist. Despite these testimonies, Diamond’s hand-picked jury ruled for its removal. Serra later criticized Diamond for acting as both juror and jury of the trial.

After it was removed in 1989, the Arc was taken apart and its pieces were stored in a government parking lot in Brooklyn. They were then moved to a storage space in Maryland in 1999. Though a petition was created to move it to Storm King Art Center in Mountainville, New York, Serra said that Tilted Arc will never be displayed again other than at its original location because it was designed specifically for the Plaza.

| 1981 | Tilted Arc installed |

| 1985 | Public hearing held |

| 1989 | Tilted Arc removed |

| internal | gDoc |

| link | "The Tilted Arc Controversy" by Richard Serra |

Two downtown New York office buildings are outfitted with eye-catching and charming sculptures from Jeff Koons’ Celebration series. His signature metal balloon statues are part of the inflatable toy series he began in the 1970s. Koons’ neo-pop style is both beloved and criticized for the way in which it elevates kitsch to high art, but the appeal of his work is undeniable, considering that one of his giant metallic sculptures is to date the most expensive work of a living artist to sell at auction. The Celebration series consists of the same few balloon forms in five variations of monochrome color – yellow, magenta, red, blue, and orange.

When exploring the Financial District it’s worth stopping by the outdoor plaza in front of 7 World Trade Center to see Balloon Flower (Red). The most recent Koons to be publicly installed is his Balloon Rabbit (Red) in the lobby of the new IBM Watson Building on Astor Place. The Rabbit, first made in 1986, is one of his most famous works to date. Part of the mass appeal of Koons’ Celebration series is how the viewer’s reflection becomes part of the piece.

The publicity he receives for his Celebration Series statues is a positive departure from Koons’ earlier infamy, gained from his sexually explicit Made in Heaven series, shown at the 1990 Venice Biennial, for which he posed with his pornstar wife, Ilona Staller. Koons allegedly destroyed the Made in Heaven series after the marriage ended on bad terms and Staller left him, taking their son.

| 2008 | Balloon Flower (Red) installed |

| 2014 | Balloon Rabbit (Red) installed |

| link | Sleek, Intelligent Design |

| article | Installation View: Jeff Koons’ “Made In Heaven” Series (XXX) |

| article | 51 Astor Place Ready for Business |

| article | Koons Sculpture Adorns Lobby at Astor Place |

| internal | gDoc |

When the Temple Court building on 5 Beekman Street was completed in 1883, it was one of the first high-rise buildings in New York. It was commissioned by developer Eugene Kelly to serve as a law office building and was named Temple Court after Britain’s infamous legal district in Temple, London in the hopes of attracting lawyers and law firms. Architects Silliman and Farnsworth used the most modern styles and materials of the time for its construction. Its terra cotta and hollow brick facade made it one of the earliest fire resistant buildings in the city, while its Renaissance Revival and neo-Grec interior made it one of the most ornate and up-to-date.

Before the construction of Temple Court, however, the site held one of the first theaters in New York. The Chapel Street Theater was built in 1751 by English actor David Douglass when he emigrated from Jamaica to New York. He also owned another early playhouse not far from this one. The Chapel Street Theater would go on to host New York’s first performance of Hamlet, one of William Shakespeare’s most famous plays. The building is believed to have been torn down by rioters in 1766 due to tensions between American patriots and English colonists in the years leading up to the Revolutionary War.

Theater was virtually nonexistent in New York before British colonization when the city was under Dutch rule. Both culturally and socially, theater was a central part of English life, and colonists wanted to experience theater in America as they did in England: English plays with an entirely English cast. Because of its close British ties, theater was banned in 1774 in the wake of the American Revolution. After the war, however, theater boomed and became an important part of American culture. Old theaters reopened, and new ones appeared. In the 1920s and 30s, these theaters began hosting musicals. This eventually gave rise to Broadway and established New York as a theater metropolis.

In 1998, Temple Court became a landmark and went on and off the market until it was bought by GFI Developments in 2012. The building, after a long stretch of laying unused, is now being restored and will become Beekman Residences, a luxury hotel and condo complex.

| 1626 | Dutch purchase Manhattan from Native Americans |

| 1665 | British take over New York |

| 1751 | Chapel Street Theater is built |

| 1766 | Theater is torn down by rioters |

| 1774 | Continental Congress bans theater |

| 1883 | Temple Court is built |

| 1998 | Temple Court becomes a landmark |

| 2012 | GFI Developments buys Temple Court |

| internal | gDoc |

The African Burial Ground National Monument at 290 Broadway marks the oldest African burial site in North America. As the city began to expand, the cemetery was built over and forgotten until 1991, when the remains of over 419 freed and enslaved Africans were discovered during the construction of a federal office building. The burial ground spans nearly 7 acres from the northern edge of City Hall Park to Chambers Street and Broadway, to the Municipal Building at Chambers and Centre Street, then north on Centre to Duane Street.

The Manhattan slave trade began with the Dutch settlers in 1626 when the Dutch West India Company began importing its first slaves from West Africa. Unlike the English, the Dutch allowed slaves to reach partial to full freedom status. Freed slaves were allowed to marry and buy land, and they soon began purchasing land in the area between City Hall and 34th Street. When the British took control of Manhattan in 1664, however, slaves were stripped of many of the rights they were given under Dutch rule, including the right to bury their dead in churchyards. After this ban, Africans began using this area, which was just outside of the city’s limits–as a cemetery. It is estimated that over 20,000 were interred in the 7-acre plot between 1690-1794.

It was found in 1788 that the Burial Ground was being desecrated by medical students and doctors for medical purposes. Because acquiring corpses for educational purposes was both difficult and virtually unheard of at the time, fresh bodies were exhumed from the cemetery in the winter of 1788 at an alarming rate. When a group of freedmen noticed the students and physicians–who at the time were referred to as Resurrectionists–they petitioned the city council to take action against it, but their request was ignored.

In April 1788 citizens stormed New York Hospital, where the dissections were held, and widespread rioting soon broke out. The few remaining physicians in the city were forced into hiding when a mob of 2,000 people gathered on Broadway in an attempt to find John Hicks, a medical student whom they felt was to blame for the atrocities. Militia and cavalry were called to break up the crowd and repel the protesters. As a result of the incident, public opinion of New York City physicians remained low for decades. In 1789, a statute was passed to punish those who violated the laws against the proper treatment of corpses. Despite the implementation of the law, however, the atrocities continued.

The Burial Ground became a National Historic Landmark in 1993. In 2005, the GSA chose architect Rodney Leon’s design for the memorial on the corner of Duane and Elk Streets, which is 25-foot granite monument that features a map of the Atlantic in reference to the Middle Passage, the stage in the triangular trade in which slaves were transported from Africa to North America. In 2006, President George W. Bush designated the burial site a National Monument.

| 1690 | Area became cemetery |

| 1788 | Residents storm New York Hospital |

| 1991 | Remains discovered |

| 1993 | Burial ground becomes National Historic Landmark |

| 2005 | Rodney Leon’s granite monument is installed |

| 2006 | Declared National Monument |

| internal | gDoc |

F.W. Woolworth, owner of the Woolworth company, wanted his company to construct the tallest building in the world. Woolworth commissioned engineer Gunvald Aus and architect Cass Gilbert, who had designed the US Custom House in New York in 1899. Gilbert designed a 625-foot tall skyscraper, but that was not tall enough for Woolworth. Gilbert made some additions, and the tower reached 792 feet. Woolworth paid approximately $13.5 million to have the tower built. The Gothic-style skyscraper had a grand opening ceremony, for which President Woodrow Wilson pushed a button and turned on all the lights in the building – allegedly from his desk in the Oval Office.

| 1859 | Cass Gilbert born |

| 1907 | Gilbert becomes president of the AIA |

| 1913 | Woolworth Building opens |

| 1934 | Gilbert dies |

| internal | gDoc |

Beverly Pepper’s “Manhattan Sentinels” stand guard over Federal Plaza. The thirty sculptures, over 36 feet tall, are arranged in groups of three throughout the plaza to resemble trees. Richard Serra’s “Tilted Arc” was formerly located near where Pepper’s sculptures are today and divided the plaza, but Pepper created her massive steel sculptures with the intention to create an environment and that “Manhattan Sentinels” would become part of the landscape. Pepper, born in Brooklyn in 1922, has been working in steel and other metals since she and her husband moved to Italy in 1956. Despite her age, Pepper is still an active sculptor.

| 1996 | Manhattan Sentinels installed |

| internal | Beverly Pepper - Wiki |

| link | Beverly Pepper |

| article | Interview with Beverly Pepper - The Telegraph |

| internal | gDoc |

A natural fresh water source for Manhattan’s earliest settlers, Collect Pond was a hotspot for recreation all throughout the year. Smaller streams branched out from the pond’s core, connecting to both the Hudson and the East River. Despite being a valuable resource to early Manhattanites, industries began dumping mass amounts of waste in the pond starting in the late 1700s. By 1813, Collect Pond had virtually disappeared and become nothing more than a polluted sewer-turned-landfill.

New York began channeling fresh water from the Croton Aqueduct several decades later, leading to the development of neighborhoods such as the notorious slum Five Points near the former pond. The Tombs, a prison, was constructed on the former pond site in 1838, but due to the swampy and unstable landfill site, its foundation began giving way and its interior became an incubator for disease due to the damp atmosphere.

In 1960, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation obtained a portion of the former Collect Pond site to construct a park. Originally named Civil Court Park to indicate the prevalence of judiciary institutions in the area, the park was quickly renamed to Collect Pond Park to more accurately reflect its history. The park is currently undergoing extensive renovations which will include a reflective pool reminiscent of the original pond, as well as additional green space with pedestrian plazas.

| 1813 | Collect Pond virtually disappeared, turned into landfill |

| 1838 | The Tombs prison constructed on Collect Pond site |

| 1960 | Collect Pond Park established |

| 2012 | Collect Pond Park renovations begin |

| internal | Collect Pond - Wiki |

| link | NYC Parks: Collect Pond Park |

| internal | gDoc |

Artistic duo La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s immersive “Dream House” is meant to be experienced, not just visited. Zazeela and Young, who are married, have been working together for over forty years, and first started “Dream House” in 1993 in an apartment on Church Street. The environment features drone-like music by Young and lights and sculptures are by Zazeela; the lights and sound change based on the visitor’s movement. Staying inside for a long period of time might cause dizziness or discomfort, but the artists say that the environment is meant to create a trance-like existentialist experience.

| 1993 | Dream House opens |

| link | Mela Foundation: Dream House |

| link | Atlas Obscura: Dream House |

| article | The Biggest Sound You've Never Heard |

| internal | Marian Zazeela - Wiki |

| internal | La Monte Young - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

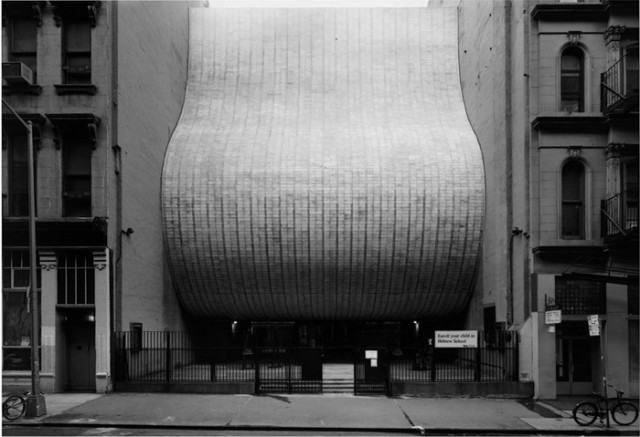

William Breger, a Bronx-born, Harvard-educated architect was hired in 1967 to design the Synagogue. Breger was chairman of the department of architectural design at Pratt at the time and his architectural practice specialised in nursing homes. The synagogue was a very different assignment, yet Breger was able to create an inspiring, thoughtful and useful space. The synagogue’s flame-like shape appears to be floating above the street, and missing any windows its sanctuary is beautifully illuminated from a skylight. The shape of the exterior corresponds to the interior, yet the outside is marble bricks and the interior wood-paneled. The materials but also its shape allow for great acoustics – which to a congregation that can’t use electricity and amplifiers on Sabbath is a very useful feature. Breger’s modern design won him the 1968 Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects, and the building was landmarked in 1992.

| link | Our History |

| link | Civic Center Synagogue |

| article | NYTimes |

Walter Martin and Paloma Munoz’s “A Gathering” at the Canal Street subway station might take you by surprise – there aren’t many birds living underground, let alone 181 of them. This sculpture, commissioned by the MTA Arts for Transit program, features three species of birds: grackles, blackbirds, and crows. They are arranged in groups of two to four, based on the birds’ natural social behavior. Martin and Munoz first did some research by watching videos of birds and examining stuffed birds at the American Museum of Natural History. They then sculpted the birds in clay, then in plaster molds filled with wax, and were then put into bronze with glass eyes. Martin and Munoz work together on projects that explore the space between fantasy and reality.

| article | Dont Feed the Birds |

| link | Snowglobes Series |

| internal | Arts for Transit and Urban Design: A Gathering |

| internal | gDoc |

Tweed Courthouse symbolizes the corruption of Boss Tweed and the Tammany Hall political machine. William Tweed led the political organization with the main goal of keeping the Tammany Hall politicians in power at various levels of the city and state government so that they would stay in power, ensure the city ran how they wanted, and make the political machine more money. The corruption manifested itself in the building’s construction; carpenters and bricklayers were overpaid with city money which then went back to Tammany Hall. Ironically, Boss Tweed was tried for corruption in this courthouse in 1873. Furthering the difficulties surrounding the project was the death of the project’s head architect John Kellum in 1871. Leopold Eidlitz took charge of construction and saw the project finished in 1881. The building went over its $250,000 budget and cost over $14 million. If this happened today, it would have been equivalent to over $170 million. The neoclassical building housed the New York County Supreme Court until 1929, then by the City Court until 1961. The building was unused for many years, but was landmarked in 1984. In 1999 the architectural firm Beyer Blinder Belle restored the courthouse. The total restoration cost $90 million, and it is now a school and houses the Board of Education offices.

| 1861 | Construction begins |

| 1872 | Construction interrupted when corruption exposed |

| 1877 | Eidlitz resumes construction |

| 1881 | Eidlitz finishes construction, courthouse opens |

| 1984 | Designated a New York City landmark and added to National Register of Historic Places |

| 1986 | Designated a National Historic Landmark |

| 1999 | Underwent a $90 million renovation |

| 2004 | Element E sculpture added to courthouse for public display |

| wiki | Tweed Courthouse |

| link | A Look Inside the Tweed Courthouse |

| wiki | Boss Tweed |

| internal | gDoc |

Tony Rosenthal’s “5 in 1” is appropriately located between 1 Police Plaza and City Hall. The sculpture consists of five large red discs connected to one another and represents the relationships of five boroughs of New York City. For this work, Rosenthal won the “First Prize Art In Steel Award.” The sculpture has been in place since 1973, and has changed considerably since its installation. Rosenthal intended for “5 in 1” to be painted red, but due to a lack of funds, the city left the raw Cor-Ten steel exposed. It was in a state of disrepair and covered in graffiti when the city was able to paint the sculpture red. However, the steel which was previously exposed caused the paint to flake off and skateboarders began to use it as a ramp. “5 in 1” was restored and repainted again in 2010.

| 1973 | Rosenthal installs 5 in 1 |

| link | Art Nerd New York: 5 in 1 |

| link | Tony Rosenthal: 5 in 1 |

| internal | Tony Rosenthal - Wiki |

| internal | gDoc |

Learn how Tony Rosenthal’s “5 in 1” and represents the connectedness of the City’s five boroughs