Greenpoint, Brooklyn, has a surprising history of bucolic green pastures and rancid oil patches. Before the 19th century this corner of Brooklyn was owned by only a few families with farms (and slaves tending them). But with the future borough of Brooklyn expanding at a great rate, Greenpoint (or Green Point, as they used to call it) could no longer remain private. Industries like ship-building and petroleum completely changed the character of Greenpoint’s waterfront, while its unique, alphabetically-named grid of streets held an extraordinary collection of townhouses. By the late 19th century, Polish immigrants would move on the major avenues, developing a ‘Little Poland’ that still characterizes the neighborhood. But big changes are coming to Greenpoint thanks to new housing developments. How will these new arrivals fare next to the notoriously toxic Newtown Creek, a body of water heavily abused by industry?

ALSO: The world that young Patricia Mae Andrzejewski may have experienced in her childhood days before becoming a major rock star.

| link | Listen to the podcast |

Williamsburg bridge Plaza is major transit terminal at the foot of the Williamsburg bridge in Brooklyn. The terminal has been around since the opening of the Williamsburg Bridge in 1903. The Plaza originally served as a hub for trolleys and when the New York Department of Transportation took over operation in 1951, it became a modern day bus station. The Department of Transportation completed a major renovation of the terminal in 2015.

The John Bowne House is located in the Flushing Neighborhood of Queens. It was built in 1661 and its owner, John Bowne, was arrested during a Quaker meeting inside the house in 1662. The house was also used as a stop on the underground railroad prior to the civil war. Members of the Bowne family remained in the house until 1945. They eventually dedicated the house to the Bowne Historical Society and it was converted into a museum in 1947.

Loacated 135 feet about the East River,the Williamsburg Bridge connects the Brooklyn neighborhood of Williamsburg to the Lower East Side of Manhattan, 135 feet above the East River. The bridge opened in 1903 and and was,the longest suspension bridge in the world at the time. In addition to its two four-lane vehicular roadways, it also has two subway transit tracks, a walking path and a bike path. In the 1990’s the bridge underwent a $600 million renovation. At the Williamsburg base of the bridge sits three public areas collectively known as the Williamsburg Bridge Plaza, which contains a statue of George Washington.

Green spaces are of great importance to the bustling city of New York. Residents of the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn cherish the seven-acre East River State Park. The park sits along the East River and offers a stunning view of the Manhattan skyline. The park is located at the site of a 19th century shipping dock and contains many historical remnants of its prior use, such as cobblestone paths and railroad tracks.

This statue immortalizes Father Jerzy Popieluszko, a Polish priest who was influential in defending the rights of Polish workers and supported Polish independence from the Soviet Union. Popieluszko was kidnapped and murdered by the Polish Security Police in 1984. The statue was built by Stanislaw Lutostanski and unveiled to the public in 1990. Later that year, in an act of political activism, the statue’s head was removed. It was restored to it’s original state in 1992. Many Polish Americans gather at Father Popieluszko statue, on October 19th each year, to pay tribute to the martyr’s devotion to liberty.

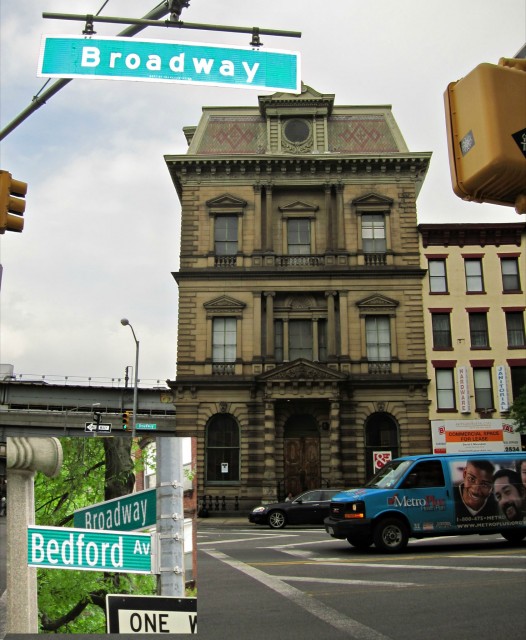

The Kings County Savings and Trust building was built between 1860 and 1867. The building’s ornate detail and luxurious appearance is representative of the French Second Empire Architectural Style that was popular during a time when it was not considered vulgar to openly display and abundance of wealth. For well over a century, the building was occupied by banking institutions. Since the 1990’s, it has been occupied by the Williamsburg Art and Historical Center.

McCarren Park is a 35-acre park named in 1909 after NY State Senator Patrick McCarren. The park is host to traditional outdoor activities such as kickball, softball and running. Because of the young, creative mix of people from the surrounding neighborhoods, it has also been the site of many unique ideas likethe McCarren Pool. The pool was built in 1936 and closed in 1984. In 2005, the space reopened and the empty pool was used as the location for concerts, dance parties and movie screenings. In 2012, after a $50 Million renovation, the pool returned to its original use and is now open for year round recreational swimming.

Built somewhere between 1916 and 1921, the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Transfiguration is a testament to the diversity of Williamsburg’s cultural heritage. It’s founders came from present day Poland who left the then Austro-Hungarian empire in search of a better life. It is the only remaining example of Byzantine revival architecture in New York, and possibly the United States. In 1980, the church was added to the National register of Historic Places. In 2008, it marked its 100th year and remains an important piece of history to the Russian Orthodox population of Williamsburg and surrounding neighborhoods.

Our Lady of Mount Carmel was founded by Italian immigrants in 1887. With mass immigration from Italy to New York, the original location at North Eighth Street and Union Avenue became too small to house its rapidly increasing congregation. A construction project for a new, larger church, at its present location, was completed in 1930. Our Lady of Mount Carmel remains an important part of the Italian-American cultural heritage of Williamsburg and is the location of an important yearly festival: The OLMC Feast, a two week summer celebration culminating on July 16th.

Since 1847, Plymouth Church has been a pulpit for civil rights, and was an Underground Railroad safehouse. Preacher Henry Ward Beecher was an influential abolitionist, and drawing huge crowds from all over to his sermons. To accommodate, architect J.C wells designed the Sanctuary building like an auditorium. Beecher also invited guests to the pulpit, including Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass and Wendell Phillips. Other speakers have included Booker T. Washington, Mark Twain, and Charles Dickens. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. even delivered an early version of his “I Have a Dream” speech here.

Looking straight out of a fairy-tale, this landmarked Federal building is one of the most elaborate in the city. Designed by Mifflin E. Bell in 1885, and finished by William A. Freret in 1891, it’s a beautiful example of Romanesque style . The interior is no less stunning, with a three-storey atrium illuminating the center.

This 1893 fortress is one of Brooklyn architect Frank Freeman’s most striking buildings, with bold brass lettering and a huge roman arch entry that dwarfs passersby. It could have been a simple warehouse, but the details elevate it to a work of art. The site was formerly the headquarters of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, briefly edited by Walt Whitman. It was added to the National Registry of Historic Places in 1974.

Gleason’s Gym is a pilgrimage for fans of both film and fight. Muhammad Ali, Mike Tyson, and Jake LaMotta are some of the greats who’ve trained there since 1977. It’s also been been the site for over 20 full-length movies, including Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull, and Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby.

The Navy Yard is a convergence of innovation and history. During the Revolutionary War, the USS Monitor, the Union’s first ironclad ship to be tested against the British, was constructed here, and in WWII the Navy Yard became a critical manufacturing center as well as shipbuilding yard. But after closing along with 90 other bases in 1966, the buildings were mostly empty, with only a few manufacturers operating. In 1987, it opened up for small and midsized businesses, quickly filling occupancy and beginning a new era. Now, buildings dating to the civil war are filled with tech innovators, and artists, and new developments include the largest film studio outside of Hollywood.

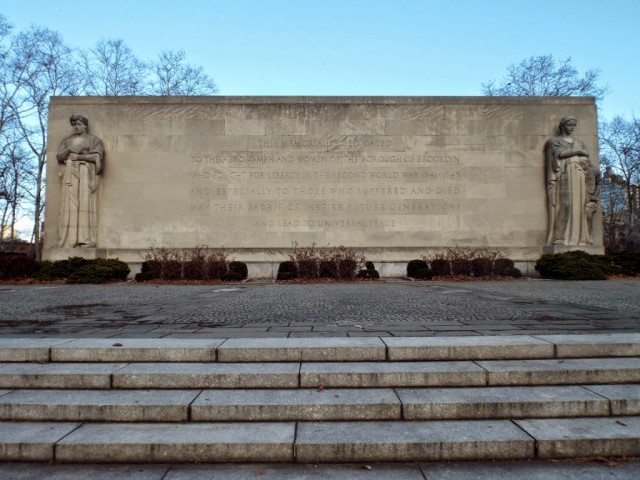

Flanked by huge sculptures of Family and Victory, this imposing memorial was dedicated in 1951 to honor over 11,000 Brooklynites who died serving in WWII. Inside is a large auditorium, and a Wall of Honor with their names inscribed. Sadly, the full plan, which included a community center and educational center, was never realized. The memorial has been closed to the public for 25 years due to lack of funding, and the site is used as storage by the Parks Department. That may change, however, as funding was awarded for repairs in 2015.

Built in 1892, this Romanesque Revival is both a city and national historic landmark, designed by Brooklyn’s prolific Frank Freeman. The fortress-like archway was designed for fire trucks to enter – possibly the city’s most impressive garage door. Firehouse operations ceased when the building was registered as a historic landmark in 1972, but the building sat mostly empty until 1987. In hopes to alleviate displacement from developing nearby MetroTech center, the city approved it as affordable housing. A 2015 renovation has restored much of its former glory, after 20 years of neglect.

In front of the new Barclay’s Center in the middle of traffic, this structure looks oddly out of place. Built in 1908, it was the entrance to the Interborough Rapid Transit line, the first regularly operated subway in New York City. When the line was finally complete, the new York TImes celebrated “A 20-mile ride from Brooklyn to 242nd Street for a nickel is possible now.” The building has been completely gutted, and now functions as a skylight for the new Barclays center station below.

A solemn shrine for some of the lesser-known casualties of the Revolutionary War, this massive Doric column marks the remains of over 11,500 American soldiers who died on British prison ships. Many were held at the docks of the nearby Navy Yard when room ran out on land, and. Despite the morbid function and sentiment, it’s a serene and peaceful spot in tree-filled Fort Greene Park, on a high hill that offers an unexpected view over Brooklyn. It’s an occasional protest site as well – In April 2015, a bust of Edward Snowden was erected here (and quickly removed).

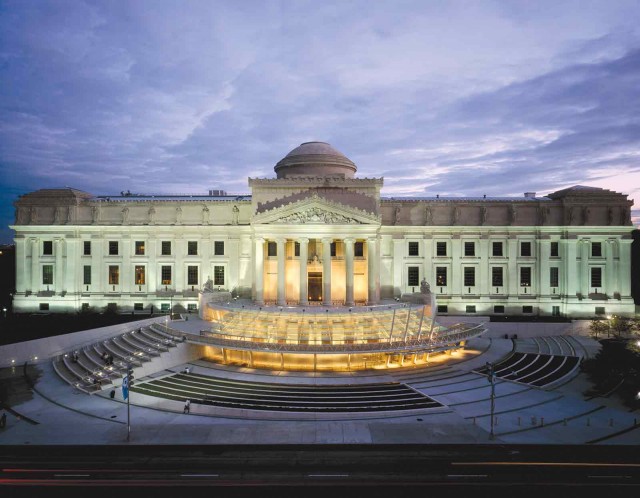

Since construction in 1895, the Brooklyn Museum’s massive Beaux-Arts structure by McKim, Mead, and White, has struck an imposing figure. When the stairs were removed in 1934 due to structural instability, the facade became an unwelcoming cliff rising from the pavement, and visitors had to climb steep enclosed staircases to enter. In 2004, the museum sought to rectify the imbalance and open up the building with a new glass pavilion and a stepped public plaza. The outdoor space also functions as an exhibit for temporary installations, with artists ranging from Suzanne Lacy to Ai Wei Wei.

Where can you see the work of world-renowned artists without stepping into a gallery? Try underneath the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. DUMBO has always been had incredible street art, and in 2013 the Business Improvement District invited 8 artists from the neighborhood across the world to work on the Dumbo Walls Project. Located on Pearl, Jay, and Water streets, you’ll find work by Brooklyn’s own Craig Anthony Miller (aka CAM), DALeast, Stefan Sagmeister, Eltono, MOMO, Coby Kennedy, Yuko Shimizu, Shepard Fairey, and South Africa’s Faith47. All within 4 blocks of the York Street subway entrance, each piece is a strikingly different experience.

Hotel St.George, what have we done to you? In 1968, Billy Joel was lamenting the St. George’s demise on the Hassles album, Further from Heaven. When opened in 1885, the St. George was one of the largest in the city, and one of the first with electric lights, drawing celebrities from around the world. But after the owner’s death in 1921, the building went into decline. By the 1970’s, a strip club occupied the ground floor, and the building was a hotspot for crime. It was finally renovated After a devastating 1995 fire, and is now rented as student housing. The Clark street 2,3 still enters through the original lobby.

Who would want to live in a place called DUMBO? In 1978, development loomed over Brooklyn. Knowing they faced the same fate as SoHo, area artists formed a small committee to brand the neighborhood with a name so off-putting, no one would want to move there. At a huge loft party, they unveiled their proposals to the community, and “Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass” won by a landslide with its absurdity. The other option? DANYA—Down Around Navy Yard Annex.

The Harvey’s interior, which looks freshly-bombed, is a surprise to many new visitors. But the neglected look is on purpose: From 1904-1968, this was The Majestic, an opulent playhouse which fell into disrepair and was boarded up for two decades. In 1984, Peter Brook and Harvey Lichtenstein decided it would be perfect to stage the 9-hour Mahabharata, and set to remodeling it in the style of Paris’ Le Bouffes du Nord. During renovations they decided to keep the ruined aesthetic, giving patrons a surreal bridge between the building’s history, and the contemporary performances onstage.

Dragons, lizards, and lions grimace from this stunning Romanesque Revival building, designed by Frank Freeman in 1888. The colorful exterior has a history to match: Originally the home of wealthy industrialists, it was expanded when they moved out in 1919, and became the glitzy Palm Hotel. The Palm sank into financial ruin, and became a brothel, until In 1961, when the Brothers of St. Francis began renting it. Today, the building has come full circle— once again a luxury residence.

During the 1960s, Marie Menken and her poet husband Willard Maas lived in the penthouse suite, turning it into a salon of contemporary art, cinema, and literature. Even Andy Warhol got his start in filmmaking under Menken’s encouragement and guidance. Their famous parties were attended by the likes of Truman Capote, Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe (who also lived in the building), Edward Albee, and Paul Morrisey. The building houses boundary-pushing artists to this day.

Walt Whitman, “The father of free verse,” moved all around DUMBO and Fort Greene, but Ryerson Street is his only residence left standing. It was here he wrote his seminal collection Leaves of Grass. Emerson and Thoreau were also known to drop by, their Transcendentalist philosophies were a strong influence. However, Whitman drew just as much inspiration from his neighbors, filling Leaves of Grass with glowing admiration for the working class. He was also a strong advocate for public space, and you can stroll through a garden dedicated to him at the nearby Fort Greene Park.

The Civil War was not New York City’s finest hour. It may have been its worst: at 6 am on July 13, 1863, the Draft Riots began. Five days of death and destruction followed. Many New Yorkers opposed conscription and the Union Cause for many reasons. But it was mostly about money: civil wars are bad for business.

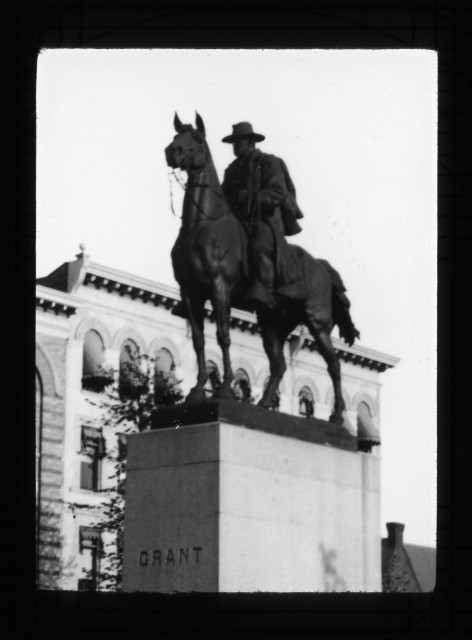

As a result, it fell to the Union League Club, an organization of prominent Republicans, to support the Union. Still going strong in 1889 they built a clubhouse at 19-29 Rogers Street in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. (Today it is the Grant Square Senior Center.) Its facade was adorned with busts of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, the Union General who defeated Robert E. Lee. But they sought a more prominent way to celebrate their Union heritage and honor Grant. In 1896, they commissioned William Ordway Partridge to create one of the first large-scale bronzes cast in the United States. The naturalistic equestrian statue is noted for its rendering of the horse and its representation of Grant. In his signature wide-brimmed hat, he looks war-weary and ready to put the conflict behind him.

No such luck.

In 1941, using WPA funds, Robert Moses restored Grant’s Tomb in Manhattan. All that was lacking was a statue to put in front of it – oh, and the money to commission or buy one. So Brooklynite Herbert M. Satterlee, President of the Grant Monument Association working with Moses, suggested taking Brooklyn’s statue. Robert Moses agreed.

Brooklyn pitched a fit.

Perhaps still rueing “The Great Mistake of 1898” when Brooklyn went from being the nation’s third-largest city in the nation to a borough of the consolidated City of New York, the community was in no mood to give a Grant to Manhattan. Brooklyn’s veterans – including United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Kings County Allied War Veterans and Robert G Summers, the last living Civil War veteran in Brooklyn who lived a block away from Grant Square – complained. The Society of Old Brooklynites, descendants of some of Brooklyn’s oldest families complained. People who didn’t know where the statue was complained.

Robert Moses withdrew his request, revealing that even if Brooklyn had donated the statue, the money to move it was lacking.

Two years later, fearing another hijacking, George Trumpler, one of Brooklyn’s most prominent citizens, attempted to move Grant eight blocks away to Grand Army Plaza, where his future might be more secure. Again Brooklyn howled. John Cashmore, Borough President of Brooklyn, finally ended the debate, reminding Brooklynites that – wait for it – the money to move it was lacking.

General Grant, the 18th president of the United States, has been left in peace ever since, perhaps the first Brooklynite whose fortune improved due to a lack of money.

— Carol Cofone

| sight | Grant's Tomb |

Much of what you see as you look at the Brooklyn Bridge depends on where you stand.

Look at it architecturally and you’ll notice its piers: Constructed of limestone and granite with gothic arches, they stand 276 feet and 6 inches above the high water line, 117 feet above the roadway. (Some believe that when the bridge opened on May 24,1883, the piers were the tallest structures not only in New York, but also in the Western Hemisphere. However, the 281-foot spire of Trinity Church, built in 1846, was higher.)

Look at it as an engineering feat and you’ll concentrate on its wire cables. Each of the four steel cables that support the 85-foot wide bridge deck measure 15 ¾ inches in diameter and 3,578 feet, six inches in length. Each cable consists of 5,434 individual wires with a total length of 3,515 miles protected by 243 miles, 943 feet of wire wrapping. Each one weighs 1,732,086 pounds. These cables enabled John Roebling, the designer and builder of the bridge, to build the first steel suspension bridge spanning a record 1,595 feet, 6 inches.

If you look at it in human terms, you’ll consider that between 20 and 30 people lost their lives building this bridge. John Roebling was among them. While conducting survey work for the Brooklyn pier, his foot was pinned against a dock by a ferry. After a few weeks of ineffective self-treatment, on July 22, 1869, he died from tetanus. His son, Washington Roebling took over construction. He got the bends from ascending too quickly in the caissons used for under-water excavation. He was paralyzed for the rest of his life. He viewed construction through a telescope from a window of his house in Brooklyn Heights while his wife, Emily, managed the construction on-site. By the time the bridge was completed, many assumed she was the chief engineer. When the bridge was completed, Emily was the first to ride over it.

Six days later, on May 30, 1883, an unprecedented number of people crossed the bridge on foot. A woman stumbled on the stairs, shrieked and started a stampede of people who feared the bridge was collapsing. Twelve were trampled.

If you look at the bridge in animal terms, you’ll find that on May 17, 1884, P. T. Barnum led 21 elephants, including Jumbo, from Manhattan over the Brooklyn Bridge, proving that it was strong and stable and putting to rest the fears that triggered the stampede. Today the bridge is home to some of the estimated 20 pairs of nesting peregrine falcons that live in New York.

If you look at it through an artist’s eyes, you’ll see not only a “physical bridge that stands astride the East River,” but a cultural bridge “of the mind and the imagination.” That bridge stands in the writings of Hart Crane and in the photography of David Hockney, to name only two who have been inspired by the sight of the Brooklyn Bridge.

– Carol Cofone

| 1867 | John Roebling presents design for bridge across East River |

| 1869 | John Roebling is injured and dies of tetanus |

| 1872 | Washington Roebling incapacitated by "caisson disease” |

| 1883 | Bridge completed |

| tidbit | Bridge Jumpers |

Science fiction writer Douglas Adams’ famous quote, “It’s not the fall that kills you; it’s the sudden stop at the end,” is a modern cliche. But at one time, it was unheard of. In New York, in the late 1800’s, when tall buildings and skyscrapers began to appear, some caught fire. Their occupants were beyond the reach of fire department ladders, but they were afraid to jump into safety nets held below, believing that plummeting from a height would suffocate them.

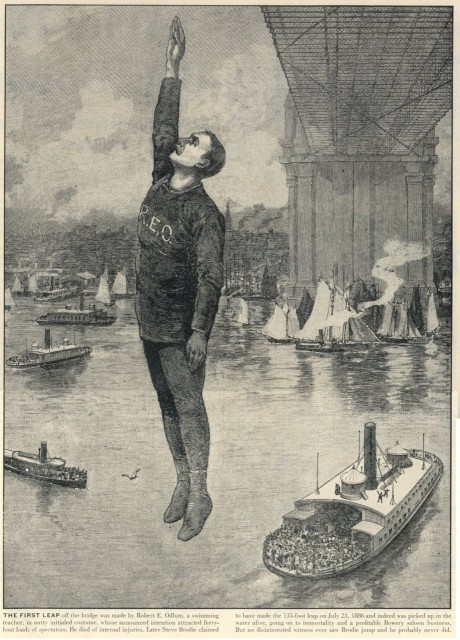

Enter Robert Emmet Odlum, a swimming instructor from Washington, DC with a passion for safety. He believed that everyone should learn to swim, and learn to jump in a high-rise fire. He made it his mission to prove that you could breath while falling. He did so successfully from a series of ever-greater heights. At least for awhile.

By 1885, the Brooklyn Bridge had become an object of fascination. Having previously jumped from 110 feet, expectations grew that he would become the first to jump 130 feet from this famous bridge, into the East River. It didn’t work out well. Evading police efforts to prevent it, with thousands of onlookers watching, he jumped at approximately 5:30 on May 19. He held one hand high above his head as a rudder to try to control his descent. But he began to slant. His right side impacted the water and he disappeared. When he surfaced, he was floating face down. He was rescued from the water, unconscious. He briefly showed signs of life, opened his eyes and asked if he had made a good jump. However, he had ruptured his kidneys, liver, and spleen, and died of his injuries less than an hour after his jump. Despite the sad outcome, Odlum became famous. Others then tried to capitalize on it by taking the same leap into the East River, or at least pretending to.

The second bridge jumper was Steve Brodie, described by the New York Times as “a newsboy and long-distance pedestrian.” Either he jumped from the Brooklyn Bridge, or a dummy did so while Brodie fell out of a row boat, on July 23 in 1886. His motives were not nearly as altruistic. Either he wanted to win a $200 bet, or he wanted to be famous. That, he did accomplish. He also opened a saloon at 114 Bowery near Grand Street, which he fashioned into his own bridge-jumping museum. His fame lives on today: in the slang phrase, “do a Brodie,” meaning to take a suicidal leap; and in the 1965 musical Kelly, inspired by Brodie’s story, so bad that it flopped on opening night – a sudden stop if there ever was one.

— Carol Cofone

| 1885 | Robert Emmet Odlum jumps off the Brooklyn Bridge and dies |

| 1886 | Steve Brody does or doesn’t jump off the Brooklyn Bridge and lives |

If ever strolling the sunny lawns of the Empire Fulton Ferry section of the Brooklyn Bridge Park, be sure to take a ride on one of the 48 horses of this restored vintage carousel. Tickets are only $2 and it’s definitely worth it. The vibrant horses and chariots were first installed in Youngstown, Ohio’s Idora Park in 1922. Idora Park thrived in the golden age of amusement parks during the early to mid twentieth century. By the time a devastating fire took many of the amusements in the spring of 1984, the park was already on the decline. The carousel, named to the National Register of Historical Places in 1975, was scorched and like many of the salvageable amusements, was sold at auction by Norton Auctioneers of Coldwater Michigan. It was at this auction that The Walentas family of Brooklyn came to own the deteriorating carousel for $385,000.

Husband and wife David and Jane Walentas were on a mission to develop the area of the present day Brooklyn Bridge Park. The abandoned space was to be a marina and shopping center with a vintage carousel. David had already contributed to the building up of much of the Dumbo neighborhood, but because of opposition, his plans for the shopping center were replaced by plans for a public park.

Jane Walentas was once an art director at Estee Lauder and chose the Idora carousel because of its beautiful original carving. Though she had hired experts to restore the carousel, notably a Mercedes-Benz car detailer to complete the delicate freehand painting, Jane did much of the hard and difficult tasks herself. For years, she and a part time assistant meticulously scraped off 62 years of dirt and paint to reveal the carousel’s original palette. Once the original paint layer was revealed, Jane recorded the colors and matched them with old photographs of the carousel, which would help in restoring the horses. The horses were repainted, gilded with real gold leaf, and missing embellishments, like glass eyes for the horses, were replaced. The mechanical system was upgraded and the carousel was totally rewired to burn 1,200 bright lights. At night, when the carousel closes, the shadows of the horses are projected onto the pavilion, giving off an enchanting show.

The Walentases, who had left behind the wooden building that originally housed the carousel, hired Pritzker Prize winning French architect, Jean Nouvel, to build a $9 million acrylic encasement for the newly restored carousel. Nouvel referred to the carousel as a “jewel” in the middle of a giant square jewel box. The housing gives riders a 360 degree unobstructed view of the bridges and the East River. After years of restoration, Jane’s Carousel, a labor of love with its brilliant colors and nostalgia, opened to the public on September 16, 2011 for a new generation to enjoy and treasure. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy’s storm surge flooded the carousel with at least 18 inches of water. Though the storm spared the horses, it caused $300,000 worth of damage to the carousel’s electrical systems. One year later, to prevent future damage, it was fitted with floodgates in order to preserve Jane’s Carousel for years to come.

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Brooklyn Literary Tour |

| internal | Wikipedia: Truman Capote |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Brooklyn Literary Tour |

| internal | Wikipedia: Arthur Miller |

| internal | Wikipedia: Death of a Salesman |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Brooklyn Literary Tour |

| internal | 1 Montague Terrace |

| internal | Wikipedia: WH Auden |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Brooklyn Literary Tour |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Brooklyn Literary Tour |

| internal | Wikipedia: Norman Mailer |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Brooklyn Literary Tour |

| internal | Wikipedia: Henry Miller |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Lovecraft in Brooklyn Heights |

| internal | H.P. Lovecraft, Master of Horror, Lived in Brooklyn Heights |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Atlas Obscura |

| internal | Reed's Tomb |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Neighborhood Preservation Center |

| internal | Atlas Obscura |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Landmarks Preservation Commission |

| internal | Atlas Obscura |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Atlas Obscura |

| internal | Green-Wood Historian blog |

| internal | Neighborhood Preservation Center |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Atlas Obscura |

| internal | Wikipedia: Murder Inc. |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | Walt Whitman and the Arts in Brooklyn |

Bushwick’s Lipsius Cook House holds the strange story of an Arctic explorer, an untiring rival, and the fantastical (and fallacious) tales of their journeys to previously unreached parts of the globe.

In 1889, Catharina Lipsius, the widow of one of Brooklyn’s earliest beer brewers, commissioned Theobald Engelhart, a revered German architect at the time, to design the red brick American Round-Arched house at 670-674 Bushwick Avenue.

Though the home has had a myriad of owners since its completion in the late 19th century, its most interesting character was its second owner, physician and explorer Frederick Cook, who purchased the house from the Lipsius family in 1902. Cook became known for his claims that he was the first one to reach the peak of Alaska’s Mount McKinley and the first person to reach the North Pole. Both his expedition team and fellow explorer Robert Peary challenged the truth of his stories. Peary–who claimed that he was the first one to reach the North Pole–devoted most of his life to discrediting Cook’s allegations, which resulted in the financial and social ruin of both men.

Cook tried to defend himself against Peary’s claims, producing photographs and maps from his expeditions. His famous photograph which was allegedly taken from the summit of Mt. McKinley was found to have been taken on a tiny peak–which is now called Fake Peak after Cook’s fallacious claims–about 20 miles away from McKinley. Cook’s maps were also subject to doubt, showing paths matching those of science fiction writer Jules Verne’s fictional Arctic expeditions. Peary and the public continued doubting Cook after it was found that all of Cook’s travelling companions gave different accounts of their trips with him.

Though Peary claimed that he was in fact the first person to reach the North Pole, there was not much proof supporting his story either. Historians continue to debate whether either of them ever actually made it there. Despite Peary’s equally doubtful expedition tales, he successfully discredited Cook and soiled his reputation as an explorer.

As if he wasn’t already surrounded by enough controversy, Cook was found guilty of mail fraud in 1922 and was imprisoned until 1930, which resulted in the loss of his Bushwick home. The property changed hands several times since the 1920s, and has been a multiple resident private property since 2000.

| internal | gDoc (Blog Post) |

| internal | Atlas Obscura |

| internal | Wikipedia: Frederick Cook |

| sight | Neighborhood Preservation Center |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Inside Hidden Crannies Of The Astral, Greenpoint's 'Dakota' |

| link | Street View |

| internal | Ellie Balk website (photos) |

Who doesn’t love this Classical Greek inspired structure? For many people, Prospect Park begins and ends on the Park Slope side, but other parts of the park have some of the best goodies, some hidden, and some, like this shelter, in plain view. And to learn that it was designed by one of the finest architectural firms in the history of American architecture is just icing on the cake. As summer rapidly is upon us, let’s take a look at this wonderful folly on the Flatbush side of the park.

The official name of this building is the Prospect Park Peristyle, although to most, it’s called the Grecian Shelter, or the less well-known name; the Croquet Shelter. Peristyle is a Greek word meaning an architectural space, such as a court or porch that is surrounded, or edged by columns. This building is regarded in architectural circles as the finest Neo-classical peristyle in New York City. The scale is perfect, the spacing is perfect, the details are perfect, and the vaulting exquisite, it’s just damn good.

Stanford White, of the venerable firm of McKim, Mead & White, designed this shelter, along with other decorative structures in Prospect Park, when his firm got the commission to add a Neo-classical formal entrance to the park in the mid-1890s. Over the next twenty years, he, as well as other architects, added many structures to the park, many in this formal Beaux-Arts Greco-Roman inspired style. It was he who first came up with the “Croquet Shelter” name, although croquet was never played in this part of the park. But whatever…look at what we got:

The shelter is a platform with marble Corinthian capitals atop limestone columns. Everything above the capitals is terra-cotta, including the frieze, the balustrade and the vaulted Guastavino tiled ceiling. The floor is glazed beveled brick. White was a master of scale and detail, and this building was situated in such a way that the raised platform, at the top of the rise, gave those within an excellent view of both the Prospect Park lake, or the goings on at the Parade Grounds just across Parkside Avenue.

Like most things in New York City’s parks, the shelter was not maintained during the middle decades of the 1900’s. The city’s fiscal crisis meant very little money for parks, and with issues of safety, crime, and neglect, this building, like many others in the park, was not maintained until 1966, when a major rehab took place. The structure was landmarked in 1968, and it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971. It survived until 1996, when the Parks Department made its restoration one of their capital improvement projects, and it was restored to its original glory. Today, it still stands as a landmark on this side of the park, a startling, but elegant piece of ancient Greece amidst the trees, lake and pathways of Prospect Park.

via brownstoner.com

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Prospect Park Peristyle |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | Keeping House: Hendrick I. Lott House |

| internal | Remembering Africa |

| internal | gDoc TBC |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | Cemetery website |

| internal | Wikipedia |

| internal | Brooklyn Lyceum - Public Bath No. 7 |

| internal | gDoc TBC |